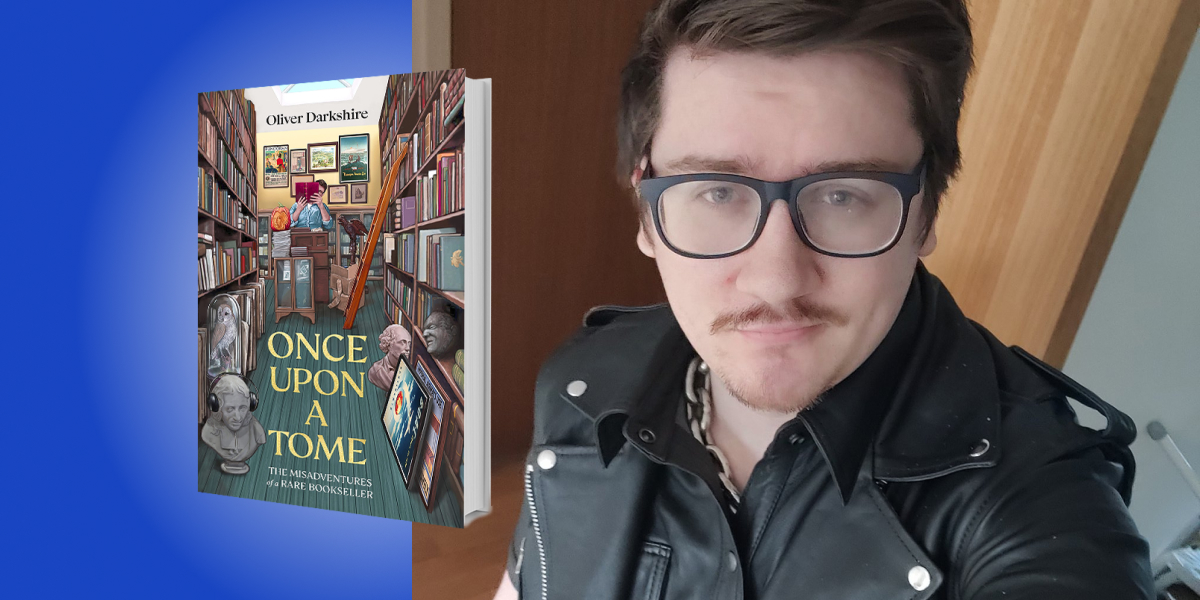

Oliver Darkshire is an antiquarian bookseller at Henry Sotheran Limited in London.

Below, Oliver shares five key insights from his new book, Once Upon a Tome: The Misadventures of a Rare Bookseller. Listen to the audio version—read by Oliver himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. There is always another dungeon.

A bookstore like Sotheran’s has countless hidey-holes, shadowy corners, and dusty cellars in which to dispose of unwanted books and, occasionally, particularly irritating customers. There’s no end to them, which sounds like an exaggeration but reflects the reality of the situation, which is that seven years down the line I am still occasionally asked to fetch something from a cellar I didn’t know existed.

Sometimes, people are living down there, which is something you learn to take in stride. Is it worrisome? Yes. Do I sometimes fear that the shop will come crashing down under the weight of all those accumulated secrets? Also, yes. Is there anything to be done about it? No. I just have to make sure that I don’t lose any of the hundreds of miscellaneous keys scattered about the shop, because marching around the catacombs of London carrying a gigantic set of bolt cutters invites all the wrong kinds of attention.

2. If you love something, let it go.

A consequence of having unlimited dungeons is that there are unlimited places for things to go missing. Books go on walkabouts, this is just accepted fact. When you first start working in a bookstore, you take this lamentably practical view of things. “It can’t possibly have vanished into thin air!” you say out loud, as if that will make a shred of difference, because it absolutely has.

“You learn to accept that physical books do have a mind of their own, and they will appear when they feel the time is right.”

After a while, when the fires of enthusiasm for bookselling have faded to a maintainable ember, you learn to accept that physical books do have a mind of their own, and they will appear when they feel the time is right. Every year, Sotheran’s vainly attempts a stock-take of all the books, more out of a sense of duty than anything else and every year we find that half of them have discorporated into smoke. This might sound like a tragedy, but they always return, usually several years after it would have been useful to find them, and in a place you searched thoroughly several times over.

3. Don’t go towards the light.

Old books have one true enemy, and that is sunlight. The vast majority of advice we end up giving to people when we sell them rare books is that they should buy some excellent curtains and never open them again.

Light and heat will destroy a book much quicker than you’d think, bleaching the covers and making the pages curl, and once it’s happened, there’s very rarely a way back. Thinking about it, this probably explains all the dark, cold cellars. This often leads collectors to keep all their books in boxes, hidden away somewhere cold. This is probably the best move to preserve them, and they’re following our advice, but perhaps that also means no one is really enjoying them. Is the book still worth anything if it never sees the light of day? Perhaps for something to have meaning, we must accept that it will eventually come to an end.

4. Always keep buckets.

It rains a lot in England, but even when it doesn’t everything is always a bit damp under the surface. Old buildings have it the worst, and bookstores generate leaks with a consistency that almost seems vindictive. If sunlight is the number one enemy when it comes to keeping books from disintegrating, then damp is a close second.

“Light and heat will destroy a book much quicker than you’d think.”

Alas, an ill-advised paving feature in the street above the bookstore means that when it rains, we get to experience a live re-enactment of the Fall of Atlantis. The time-honored solution to this, because the city of London has no interest in any task so prosaic as fixing their pavements, is buckets. Stacks of buckets, actually, which are placed in a long line whenever it rains to try and catch the worst of it. You have to hop over them to get past, yes, but the alternative is squelching around in wet shoes because the salary of a bookseller means my boots have almost as many holes as the pavement.

5. Confusion is the best defense.

Rare books are a tricky thing to sell without getting stolen from, because there are so many of them on so many shelves, and one cannot have eyes in the back of one’s head (at least not without very expensive surgery). We’ve tried various methods across the centuries to try and deter the people who wander in looking to make off with precious things. We put in CCTV, we tried putting tags in the books, and we hung up pictures of people who’d been seen taking things.

Nothing works quite as well, however, as a good old-fashioned lock and key. The canny modern thief takes advantage of easy situations, when you’re busy or distracted. Our most reliable defense is in lockable cases and extremely confusing keychains that have a great many redundant keys. The way I see it, if I don’t know where anything is, or how to get to it, then how will anyone else work it out?

To listen to the audio version read by author Oliver Darkshire, download the Next Big Idea App today: