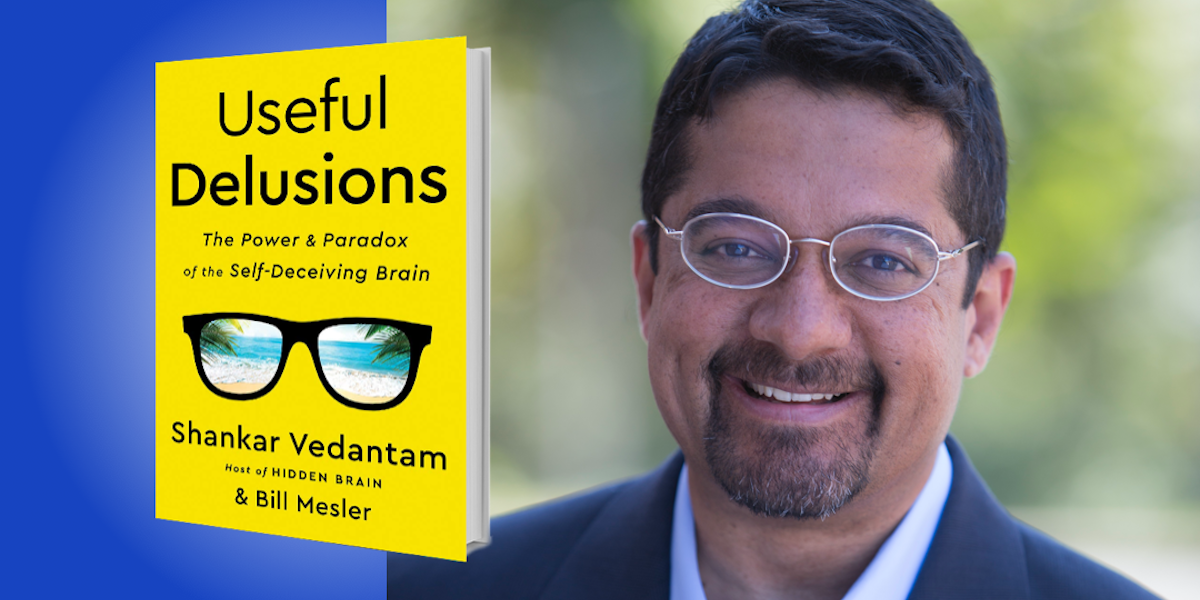

Shankar Vedantam is the host and executive editor of the Hidden Brain podcast and radio show. From 2011 to 2020, he was a social science correspondent with NPR, before which he was a national correspondent at the Washington Post.

Below, Shankar shares 5 key insights from his new book, Useful Delusions: The Power and Paradox of the Self-Deceiving Brain, co-written with Bill Mesler and available now from Amazon. Download the Next Big Idea App to listen to the audio version—read by Shankar himself—and enjoy Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Self-deception can sometimes be good for you.

In the late 1960s, Donald Lowry, a balding middle-aged writer living in a small Midwestern town, invented a series of characters—young women—whom he called “Angels.” Lowry began penning love letters in the voices of these Angels and sending them to thousands of men across the country. He formed an organization called the Church of Love, and in its heyday, the church had as many as 30,000 members. Those members were expected to send donations—or as Lowry called them, “love offerings”—in return for a steady supply of letters, and over the course of many years, Lowry extracted hundreds of thousands of dollars from people across the country.

When Lowry was finally arrested in the late ’80s and put on trial for mail fraud, several members of the Church of Love showed up to speak in his defense. That’s odd, right—why stand by the man who conned them? It turns out that for many of those men, the letters they received from the Angels were an important lifeline, a glimmer of hope that helped them stave of depression, anxiety, and, in some cases, suicide. This story is a reminder that while self-deception can do a great deal of harm, it can also do some good.

2. Delusional beliefs are vitally important to making us happy.

We all know that 50 percent of marriages end in divorce, but if you ask a couple on their wedding day, “What are the odds that this isn’t going to work out?” it’s unlikely that they’ll give themselves a fifty-fifty shot. And that’s a good thing; people who believe their partners are more beautiful, intelligent, and compassionate than they really are, are likely to be in happier relationships than people who can see their partners’ true colors.

“In moments of crisis, self-delusion can come to our aid.”

This, of course, is also true when it comes to our children. Many of us believe that our kids are extraordinary. This is a delusion, but it’s a useful delusion because it buffers you against the body blows of parenting. To see your children exactly as they are would make it much harder to be a good parent. And this is why, in the course of evolution, nature has seen fit to endow us with vast amounts of self-deception when it comes to people we love.

3. In an argument, self-deception can be more powerful than logic.

We often make the mistake—especially people who are deeply rational, people who believe wholeheartedly in science—of assuming that all arguments are best waged logically. But think about climate change; is presenting a climate change skeptic with yet another peer-reviewed study really going to change her mind? Of course not. If the first 677 peer-reviewed studies didn’t work on her, then why would the 678th study make any difference?

What we should aim to do instead is try to find ways to recruit the self-deceiving brain in the service of important causes. We see how well this works in sports—think of the Green Bay Packers fans who, despite frigid temperatures, stand bare-chested on the sidelines with their team’s colors painted on their chests. Where are the people who are willing to brave the freezing cold and go to great lengths to defend the integrity and safety of the planet? You would imagine that if there was anything that’s worth that kind of irrational loyalty, it wouldn’t be to your local football team; it would be the one planet that we all call home.

“Pelting conspiracy theories with logic is not only ineffective, but also counterproductive.”

4. There are no atheists in foxholes.

A few months ago, I experienced a retina detachment. I could literally see my vision disappearing before one of my eyes. At the time, I was far from home, and I couldn’t find a doctor. Miraculously, I managed to find an eye surgeon, and he kindly opened his practice for me at nine o’clock at night. He told me that I needed to be rushed into surgery immediately, or else I might lose my eye.

Of course, I did what anyone would do in a similar situation: I put all of my faith in a total stranger. Luckily, he turned out to be a brilliant doctor, and he saved my eye, for which I am extremely grateful. After the operation, however, I realized that I had trusted him not because he was a great doctor—I had no way of knowing that at the time—but because I was in a position of vulnerability. Deluding myself about his expertise allowed me to assuage my anxiety. So when we advocate that people follow logic and rationality, we’re often speaking from a position of privilege. In moments of crisis, self-delusion can come to our aid; as the aphorism says, “There are no atheists in foxholes.”

5. Some delusions are dangerous, but logic alone can’t defeat them.

Rather than trying to defeat dangerous delusions with facts and logic, we should ask ourselves, “What is the psychological purpose this delusion is serving?” When your uncle tells you the government was behind 9/11, rather than argue with him, it might be better to start with compassion and empathy. What does the belief mean to him? What would happen if he gave it up? This approach won’t eradicate all conspiracy theories, but as we’ve seen over the last year, pelting conspiracy theories with logic is not only ineffective, but also counterproductive.

To listen to the audio version read by Shankar Vedantam, and browse through hundreds of other Book Bites from leading writers and thinkers, download the Next Big Idea App today: