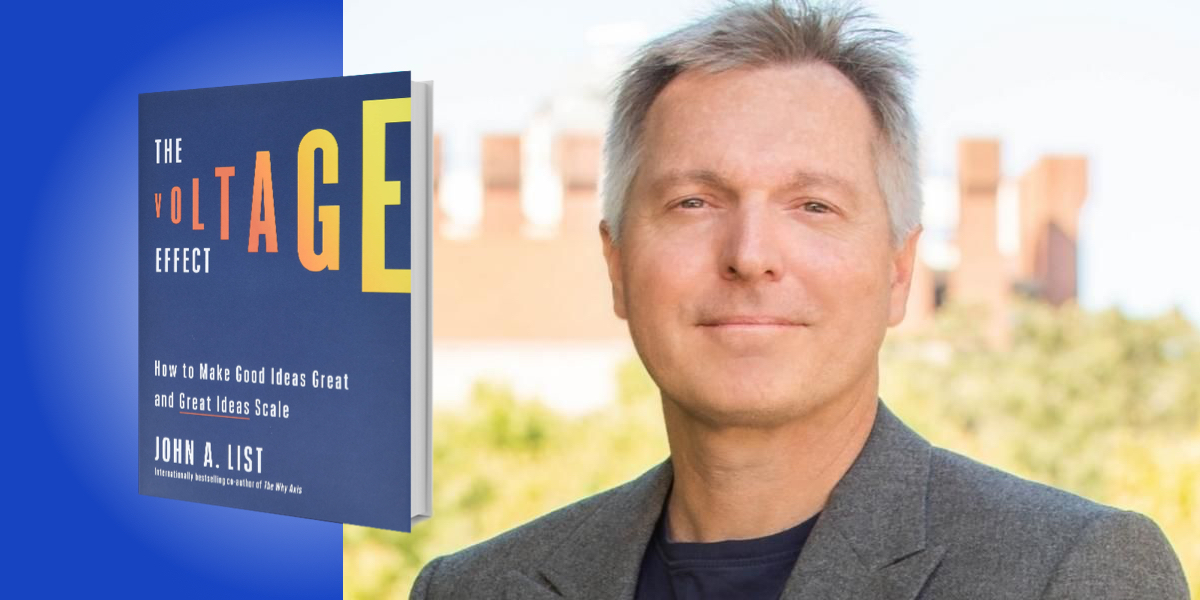

John List is a professor of economics at the University of Chicago. He is also the Chief Economist at Lyft, and Co-Director of various research centers around the world, including the John Mitchell Lab at Australian National University, the JILAEE lab in Argentina, and the TMW center at the University of Chicago.

Below, John shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Voltage Effect: How to Make Good Ideas Great and Great Ideas Scale. Listen to the audio version—read by John himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The voltage effect is the first law of scaling.

In 2007, the city of Chicago Heights asked for my help in improving their community. So in 2008 I partnered with Roland Fryer and Steve Levitt to start a preschool in Chicago Heights. We built this school from soup to nuts, and after a few years, I was very proud of the results: children improved immensely, and we were showing how a preschool can lessen the opportunity gap. I wanted every child in the world to experience my program.

But I was met with a slap in the face from policymakers. They said, “Professor List, your program had an impressive benefit profile, but don’t expect it to happen at scale.” I inquired why, and they said, “All of the experts tell us that their intervention will work, but treatment results aren’t close to what they promise.”

So, I began researching if what happens in the small is different from what happens in the large—and it was. This is what I call the “voltage effect,” which describes what happens when you move from the small to the large. A troublesome fact is that most ideas experience voltage drops, which occur when a seemingly promising idea loses power as it is scaled. The policymakers were correct.

2. Scalable ideas are all alike, but each unscalable idea is unscalable in its own way.

The policymakers had also told me that my project wouldn’t scale because there is “no silver bullet.” They had it wrong: this is not a “silver bullet problem,” but a “weakest link problem.” If weak enough, the weakest link in the chain will cause a failure. Think of an automobile where one blown tire ruins the whole trip. But just because there are numerous ways to fail when scaling, this doesn’t mean we are shipwrecked.

I have identified the five specific and universal causes of the voltage effect. If you understand each of the five vital signs, then you can determine if your idea has the signature of something with the potential to scale.

“Scalable ideas are all alike; every unscalable idea is unscalable in its own way.”

The first vital sign is false positives—these are cases where there was never any voltage in the first place, though it appeared otherwise. The second is overestimating how big a slice of the pie your idea can capture. Often this is the result of failing to know your audience, or assuming that the small subset of people who have bought into your idea are more representative of the general population. The third is failing to evaluate whether your initial success depends on unscalable ingredients—unique circumstances that can’t be replicated at scale. The fourth is when the implementation of your idea has unintended consequences, or spillovers, that backfire against the idea. And the fifth is the supply-side economics of scaling—for instance, will your idea be too costly to sustain at scale?

Leo Tolstoy began his novel Anna Karenina with the famous opening line, “Happy families are all alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” This “Anna Karenina principle” applies to scaling too: scalable ideas are all alike; every unscalable idea is unscalable in its own way.

3. Unique humans don’t scale, and a little game theory shows why.

Anyone who has read the book or watched the movie A Beautiful Mind knows who John Nash is—the famous West Virginian known as the father of game theory. But I want to introduce you to a lesser-known hero of game theory, the German mathematician Ernst Zermelo. A puzzle he was devoted to ended up playing an important role in early game theory.

Some four decades after Zermelo published his famous theorem, mathematicians in the 1950s combined his work with the concept of backward induction. Backward induction is key to scaling. That is, when conducting our original research in the small, we must backward induct from what our idea will look like when fully scaled—with all the necessary warts and constraints we face in the large accounted for. This means we must eschew the dominant approach of today—evidence-based policy approach—and instead embrace a policy-based evidence approach.

“Unique humans don’t scale, and trying to teach genius is a fool’s errand.”

For an enterprise to hold strong at scale, first you need to understand your non-negotiables—what were the drivers of the initial success? Consider a restaurant, where the success of the original eatery might be due to a brilliant chef with a unique style, or great ingredients. Before anything else, you must determine if your secret sauce is the chef or the ingredients. In other words, did your initial success rest largely on indispensable people or the product itself?

Since people don’t scale well, talent-centric ventures often don’t either. You can’t afford all the talent you’ll need as you grow, so you hire fewer high-performers, and quality suffers at scale—a cruel voltage drop. This is why truly great restaurants rarely become chains. Unique humans don’t scale, and trying to teach genius is a fool’s errand.

4. Spillovers lurk everywhere.

In 1968, a flagship federal law was passed requiring all personal vehicles to be outfitted with seatbelts. The argument was that it would stop a tremendous number of traffic fatalities. Flash forward to 1975 and my colleague Sam Peltzman examined mounds of data, concluding, “One result that can be put forward most confidently is that auto safety regulation has not affected the highway death rate.”

How could that be? As it turns out, people wearing seatbelts adjusted their driving habits and put the pedal to the metal, undoing the positive effects the federal government aimed to create. This is an example of an unintended consequence, and it represents one kind of spillover effect.

On the other extreme are market-wide impacts that influence your idea at scale. When I was the Chief Economist at Uber in 2017, we tried to raise driver pay by both changing the rate card and allowing tipping in the app. When only a handful of drivers were affected, everything went swimmingly: higher hourly pay, and drivers worked more hours. But when every driver was affected, the market arrived at a new equilibrium whereby drivers worked more hours but their hourly pay was no different than before the policy change. The reason is that they now drove around with an empty car more often than before.

“We don’t quit because society has taught us that quitting is repugnant. If only we could label it as pivoting, then we might have different social norms around quitting.”

Of course, positive spillovers exist too, such as network effects, which make a social media platform more valuable as more people join. When designing your idea, you must anticipate spillovers and look for ways to engineer positive ones while attenuating negative ones.

5. Quitting is for winners.

From the day we are born, we are taught the opposite of this idea. Consider my life, a child growing up in small-town Wisconsin, the kingdom of the legendary Green Bay Packers football coach Vince Lombardi, who famously said, “Winners never quit, and quitters never win.”

But I am here to tell you that we don’t quit enough. The reasons are two-fold: first, we don’t quit because society has taught us that quitting is repugnant. If only we could label it as pivoting, then we might have different social norms around quitting. The second reason we don’t quit is our own fault: an internal, psychological bias that leads us to ignore the opportunity cost of time. The fact is, we rarely think beyond our current situation.

We don’t consider that being a data scientist at Lyft means I am foregoing the chance to be a data scientist at Shopify. Research shows that people tend to quit their jobs only when something in their current job goes poorly, like a boss no longer appreciates you, you didn’t get a deserved raise or promotion, or you don’t get along with a co-worker.

We should be just as likely to move jobs when our opportunity set improves—that is, when the job choices we have available to us improve, that should be a draw for us. We should periodically examine our choice set because our lives will be better when recognizing the opportunity cost of our time.

To listen to the audio version read by author John List, download the Next Big Idea App today: