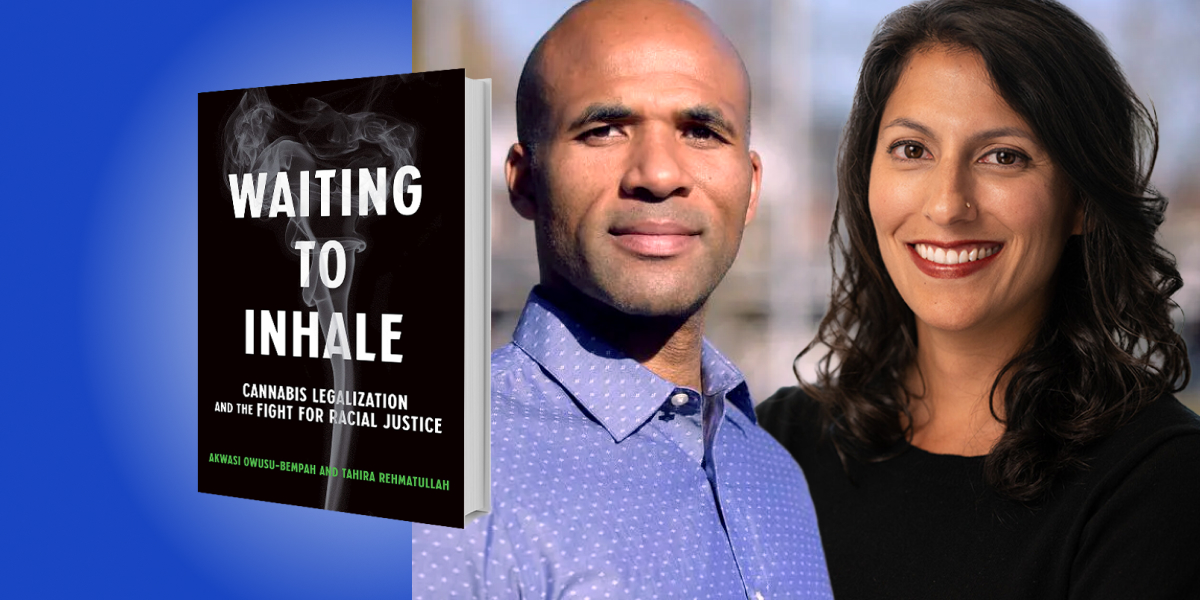

Akwasi Owusu-Bempah is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Toronto, and a Senior Fellow at Massey College. He also serves as the Race Equity Lead at the Center on Drug Policy Evaluation and holds Affiliate Scientist status at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Tahira Rehmatullah is a partner at Highlands Venture Partners, a boutique investment and advisory practice focused on emerging and innovative categories. She is also Cofounder of Commons, a health and wellness products brand, and a member of the board of directors of the Last Prisoner Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to criminal justice reform.

Below, they share 5 key insights from their new book, Waiting to Inhale: Cannabis Legalization and the Fight for Racial Justice. Listen to the audio version—read by Akwasi and Tahira—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Drug prohibition is the anomaly, not the norm.

The illegality of drugs is a relatively new phenomenon. For most of human history, drugs were not only legal but readily available. Now, as a result of drug prohibition, many of us have come to see drugs as bad and that drug users are bad. We want to flip this narrative to recognize that different substances (whether they be psychedelics or drugs like heroin or cocaine) were freely used by people around the world for different religious, spiritual, or recreational purposes.

Drug prohibition as we know it today is only about a hundred years old. It emerged largely at the beginning of the 20th century as governments in Canada and the United States sought to control not only specific substances but the people that used them. In the early 20th century, first opium became criminalized, followed by cannabis, cocaine, and other drugs. With that, a new regime blossomed—and not only in North America. Americans took this fight to the world stage by influencing the United Nations to create the UN Convention on Narcotic Drugs. This development really spawned the War on Drugs which was declared by Richard Nixon in the 1970s. From that flowed harsher laws against drug use, possession, and trafficking, as well as the expansion of a criminal justice apparatus designed to wage this war.

This historical aberration has been quite damaging. That’s not to say that drugs or their use are good, but the prohibition of drugs brings with it numerous negative consequences.

2. Drug law enforcement is used as a tool of social control.

Drug prohibition has racist roots. Drug laws were initially developed, and later strengthened, out of fear of racial minority populations: Asians, in the context of opium, Mexicans regarding cannabis, and Black populations with cocaine. As we’ve seen in both the U.S. and Canada, drug laws and their enforcement can be selectively applied to certain communities or groups, such as minorities or low-income populations, to exert control over them. This contributes to over-policing and the disproportionate incarceration of these groups, resulting in a cycle of poverty and social marginalization.

“Money spent on police, courts, and corrections in the name of this drug war is money not spent on schools, hospitals, and community centers.”

Even though rates of cannabis use are similar across racial groups, Black and Brown people have been disproportionately arrested and convicted of cannabis crimes. We talk about cannabis as a gateway drug, but not necessarily as a gateway to harder drug use. Rather, it is a gateway into the criminal justice system for society’s most marginalized populations.

Drug laws can and have been used to justify increased police presence and surveillance in certain neighborhoods or communities, leading to the erosion of civil liberties and the normalization of police intrusion into people’s lives. We must also consider the billions of dollars spent on enforcing drug laws. Money spent on police, courts, and corrections in the name of this drug war is money not spent on schools, hospitals, and community centers. We can think of this in terms of transferring wealth and resources going out of marginalized communities and into the hands of criminal justice agencies and the corporations that support and supply them.

Drug law enforcement can also be used to demonize certain drugs and drug users, creating moral panic and justifying harsh punishment and social stigmatization. This can contribute to a wider culture of fear and mistrust towards drug users, reinforcing social norms and values around drug use and addiction.

3. Cannabis legalization can be used to repair some of the harms caused drug prohibition.

With legalization comes a recognition that the substance, perhaps, should never have been criminalized in the first place, but certainly that its illegal status does not benefit society and certainly not those criminalized. With legalization, as we see happening in many jurisdictions in the United States that have legalized cannabis, there is the clearing of criminal records for people who have been criminalized for activities that are no longer illegal under the new regime. This has a beneficial impact on those people, of course, but also on society more generally. Individuals with a criminal record have a more difficult time completing their education, gaining meaningful employment, securing housing, traveling, and generally engaging in social life. By clearing criminal records, we allow these individuals a greater chance to navigate society, participate in our labor force, and ultimately give back to the countries in which they live. Legalization should bring with it a measure of amnesty through expungement and pardon systems and these should be granted by the government. This will help the individuals, their families, and the communities and the societies in which they live. We call this clearing the air.

“By clearing criminal records, we allow these individuals a greater chance to navigate society, participate in our labor force, and ultimately give back to the countries in which they live.”

A second way in which legalization can be used to repair the harms of the War on Drugs is by reinvesting a certain proportion of the tax revenue generated from legal sales back into those communities that have been most harmed by prohibition. When we look at arrest or conviction records, we see clearly that there are communities that were disproportionately targeted by the police for drug law enforcement, and within which a disproportionate number of people have criminal records for drug-related and cannabis-related offenses.

A good example of an emerging regime is in Illinois, where 25 percent of the cannabis tax revenue generated by the state is put into a fund to which community organizations and other agencies can apply to fund programs that promote public health, well-being, education, and address criminal justice-related issues. Through this reinvestment, we can begin to repair these communities and help them be more vibrant, healthy places to live.

4. The top must include space for those most harmed by the War on Drugs.

There are several compelling reasons why this should be the case, but we highlight four:

Historical injustice: The War on Drugs disproportionately impacted marginalized communities that have been unfairly targeted and punished for cannabis-related offenses, leading to mass incarceration and long-lasting consequences. Creating space for those most harmed by the War on Drugs to lead and benefit from the cannabis industry is a way to rectify this historical injustice.

Economic empowerment: By providing opportunities for those most harmed by prohibition to enter the legal cannabis industry, we can create economic empowerment and generate wealth in communities that have been historically disenfranchised. This can lead to job creation, entrepreneurship, and financial stability.

Cultural diversity: The cannabis industry has the potential to benefit from a diverse range of perspectives and experiences. By allowing those most harmed to participate in the industry, we can create a more inclusive and culturally diverse industry that reflects the communities it serves.

Social responsibility: The legal cannabis industry has a responsibility to acknowledge the harms of prohibition and work towards redressing them. By making space for those most harmed by cannabis prohibition to lead the industry, we can demonstrate a commitment to social responsibility and equity.

5. Legalization can’t (and won’t) end with cannabis.

The problems that we’ve identified with respect to cannabis and its prohibition, as well as the ways in which it can be used to better society, can be extended to other drugs. We’re seeing a resurgence of interest in psychedelics as medicines, being used to treat a host of mental health problems from depression to PTSD to anxiety and eating disorders. We also see decriminalization taking hold around the world, with calls, for example, coming from Columbia to legalize cocaine.

“We’re seeing a resurgence of interest in psychedelics as medicines, being used to treat a host of mental health problems from depression to PTSD to anxiety and eating disorders.”

The lessons that have been learned from both the failures and positive elements related to legalization should be extended to other substances as the legalization of those substances takes hold. That is, recognizing the harms, seeking to clear the records of people who have been historically criminalized, creating space within these industries both on the corporate and scientific side, and using some of the wealth generated from the commercialization of these substances to be fed back into the communities that have been most harmed by prohibition.

In conclusion, the War on Drugs has been a complete failure. Unless, of course, you’re an international drug syndicate that has made millions from the illegal trade in drugs, a politician who has risen to power as a drug war crusader, or a law enforcement agency that has been well-funded and equipped in order to wage this war. Cannabis legalization is here. Now, it’s what we do with it.

Beyond legalization, we must be advocates for social justice by taking tangible steps to create a diverse and equitable industry. We must recognize and address the systemic damage created by the War on Drugs and have empathy and compassion for those affected by these policies for generations.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Akwasi Owusu-Bempah and Tahira Rehmatullah, download the Next Big Idea App today: