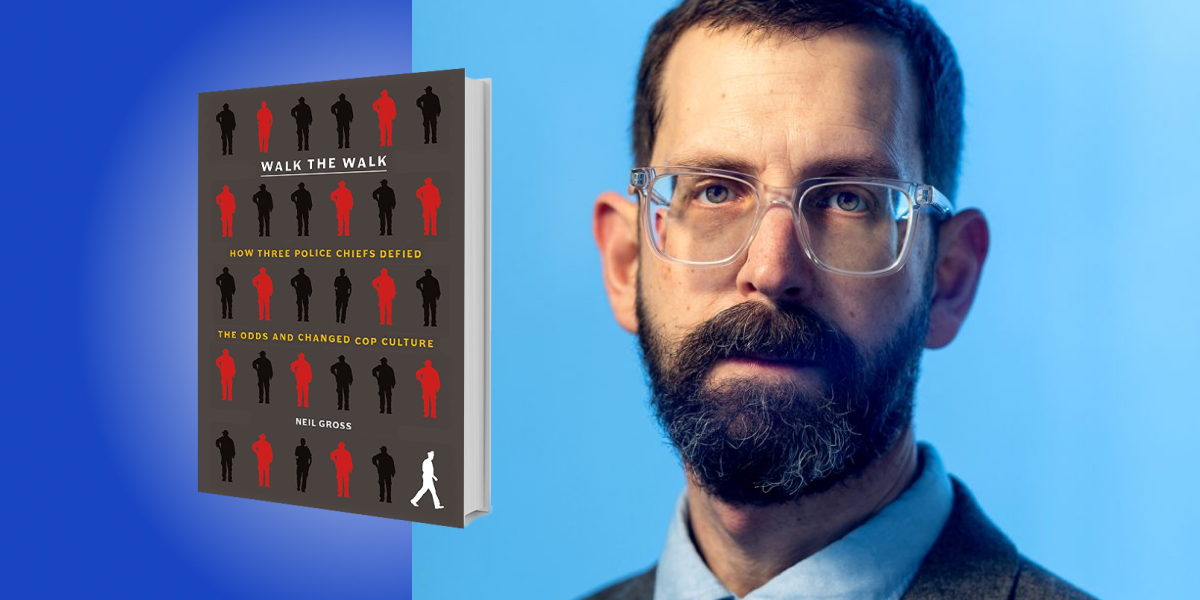

Neil Gross is a professor of sociology at Colby College in Maine. A frequent contributor to the New York Times, he is the author of two previous books and has also taught at Harvard, Princeton, and the University of Southern California. Many years ago, he served as a patrol officer for the city of Berkeley, California, in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Below, Neil shares five key insights from his new book, Walk the Walk: How Three Police Chiefs Defied the Odds and Changed Cop Culture. Listen to the audio version—read by Neil himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Cop culture matters.

When cadets go through the police academy, they’re taught the laws of their state and the policies of their department. But when they hit the street, what often influences their behavior more is cop culture: the norms, values, and mindset they pick up from their brothers in blue.

The features of this culture are well known to anyone who has ever been in law enforcement or hung out with cops. Cop culture stresses the importance of being aggressive, not showing weakness or backing down. According to its dictates, people suspected of criminal activity need to be dominated, not coddled. Policing is a dangerous occupation, and cop culture is preoccupied with danger—everyone cops interact with is seen as a potential threat. The most important thing is to always have your partner’s back, and that means not calling him out, even if he does something you know is wrong. Stereotypes abound. Cynicism, too.

Not every officer gets swept up in cop culture. But because policing is such an insular profession, the culture exerts a powerful pull, especially on young officers. It exerted an influence on me.

When you see cops engaging in disrespectful or downright cruel behavior toward citizens, usually it’s not because they’re following orders. It’s because they’ve absorbed the terrible lesson that acting that way makes someone a real cop. Until we change cop culture, imposing more policies or legal restrictions on the police isn’t likely to bring us the respectful, humane policing that so many Americans desire.

2. Culture can change.

One of the police departments I write about is Stockton. Stockton is a city of 320,000 in California’s Central Valley. It’s a blue-collar community with pockets of deep poverty, particularly among Black, Latino, and Southeast Asian residents. For decades, that poverty helped sustain a violent gang culture that’s made Stockton one of the most dangerous cities in the state.

“Just as a gang culture thrived in Stockton—among a relatively small number of its most disadvantaged residents—so too did a hyperaggressive, cowboy style of policing.”

For many years, Stockton police tried to keep a lid on the violence by inundating high-crime neighborhoods and making as many arrests as they could. Just as a gang culture thrived in Stockton—among a relatively small number of its most disadvantaged residents—so too did a hyperaggressive, cowboy style of policing. People I talked to who grew up there, especially people of color, told me harrowing stories of their experiences with Stockton PD. Many had gotten roughed up. Questionable police shootings weren’t uncommon.

In 2012, however, a new chief took the helm, Eric Jones. A longtime Stockton officer who’d grown up in a nearby farming community, Jones went into policing in the early 1990s, when the crack-cocaine-fueled crime wave of that era was at its peak. He wanted to fight crime but also cared about changing the criminal justice system from the inside—making it fairer, more equitable, and less racist.

At the same time that he was trying to contain gun violence, Jones leaned in—perhaps more than any other big city chief in the U.S.—to a philosophy of policing called procedural justice. Jones had to overcome huge challenges to get this implemented, but he was able to move the needle on police culture in Stockton. I saw it myself when riding with the department’s gang unit.

Did Stockton become a policing nirvana? No. But over the course of Jones’s decade as chief, it unquestionably changed for the better. Other departments can change, too.

3. You can’t fix what you don’t understand.

When I started the research for this project, I hadn’t been in a police car for a quarter century. So much had changed, from computers in cruisers to the use of body cams. But the day-to-day reality of dealing with people and calls hasn’t changed. In every community there’s theft and violence; there are unruly individuals, and difficult and dangerous situations. The cops get called to restore order.

“There’s often a disconnect between media portrayals of cops and the actual experience of the job.”

One of my aims in Walk the Walk was to bring readers inside the real world of the police. There’s often a disconnect between media portrayals of cops and the actual experience of the job, and that disconnect causes us to be less than clear-headed about what kinds of reforms are needed. I hoped that as a former cop-turned-sociologist, the officers I studied would trust me that much more. In the end, officers like Robbie Hall in LaGrange and Vijay Kailasam in Longmont shared far more about their lives and experiences than I could have imagined. I’ve tried to bring the police experience to the page, warts and all, to move the conversation around police reform in a productive direction.

4. You never know where a good idea will come from—so get involved.

In LaGrange, Georgia, one of the most innovative things the police chief did to transform his department’s culture might never have occurred to him were it not for a group of civic leaders. Those leaders organized a series of racial trust-building meetings between the city’s Black and white residents, and it was those conversations that led ultimately to the chief’s insight. When it comes to changing cop culture, you never know where a good idea will come from.

Sometimes it can seem like the problems with policing are intractable. While we might come out to protest a heinous injustice or cast a vote for a politician who promises reform, many of us fatalistically retreat into echo chambers, denouncing the police (or defending them) but never getting personally involved in making the institution better.

“To improve policing, we need the police to engage more with the community—but we also need the community to engage more with the police.”

Yet democracy is powered by citizen involvement. The more that we engage in difficult but constructive dialogue with local law enforcement officials about what justice means to us, what we expect of them, and what we ourselves can do to make our communities better places to live, the greater the chance that we’ll spark a change. To improve policing, we need the police to engage more with the community—but we also need the community to engage more with the police, fraught as this may be.

5. Improving cop culture doesn’t mean being soft on crime.

In one chapter, I tell the story of a horrific, gang-related gun homicide in Stockton. These homicides are among the most difficult to solve, but in this case, the trust that Chief Eric Jones had built up with the community helped lead to an arrest.

When people trust that cops are acting in good faith and aren’t biased, they’re less likely to break the law. They’re more apt to call the police when disputes arise, instead of taking matters into their own hands. If a crime occurs, they’re more likely to report it and share information about suspects. In the three cities I studied, improving cop culture by making it less hostile and aggressive improved public safety. Do cops need to fight people sometimes? Of course. But when they consistently act like jerks or tyrants, it alienates the community and makes crime worse.

To listen to the audio version read by author Neil Gross, download the Next Big Idea App today: