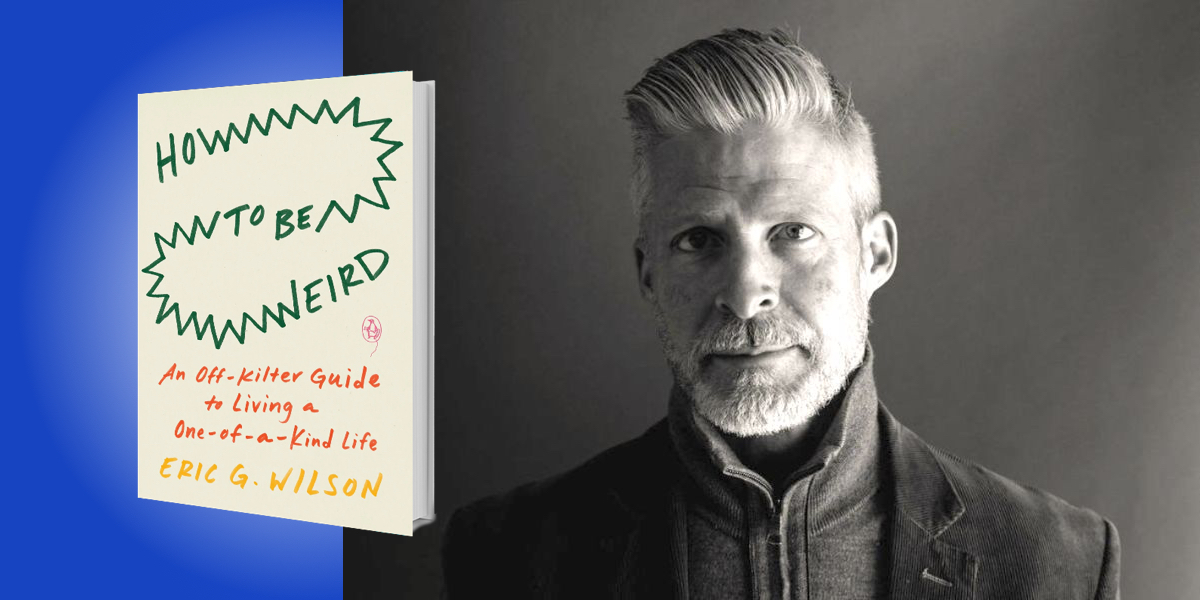

Eric G. Wilson is the Thomas H. Pritchard Professor of English at Wake Forest University. He has written many books about literature and psychology.

Below, Eric shares 5 key insights from his new book, How to Be Weird: An Off-kilter Guide to Living a One-of-a-Kind Life. Listen to the audio version—read by Eric himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Defamiliarize the familiar (see old things in a new way).

One of the great problems of life is how to keep it interesting. Many of us rely on the same routine almost every day, with the same people, from week to week and year to year. And while binge-watching television or drinking a little too much or trying to learn a new hobby offer distractions from monotony, at the end of the day, it’s the same old, same old.

That is, until you make the same old feel different by defamiliarizing the familiar. This is where weird comes in. Lie on your belly in your front yard or in a much-visited park or even on the sidewalk in front of your apartment. Stare at this ground for one minute, noticing the grass, acorns, a pebble, a stain on the pavement. Now, roll over and fling your sight into the sky. Enjoy the slight vertigo, the jerk from small to immense. Take in the heavens for a minute, and now roll back over. The ground isn’t the same anymore. It is different, alive. Take a souvenir from your adventure—a blade of grass, a picture of the stain. Put it beside your bed. It will remind you that you’re always only a turn away from re-enchanting your world.

There are many ways to disorient yourself slightly from the every day. Learn to write your name with your non-dominant hand. Imagine a secret name for a part of yourself you’ve rarely shown the world; carry the name in your wallet, and when things get stressful or boring, remember it’s there—it’s you, living out a life other than this one.

Weird experiences estrange us from our conventional habits of thought and perception, they nullify old conceptual maps, launching us into uncharted regions of our being where we can discover new coordinates, more capacious and colorful.

2. Familiarize the strange (see new things intimately).

Sometimes the daily grind can be too much even for a defamiliarizing imagination. This is when it is time to seek new terrain. No need to go far. On a Saturday, take a walk in a place in your town or city where you’ve never been. Your goal is getting lost. (Don’t worry; your smart phone will get you home safe.) Once you are beyond familiar terrain, wander just to wander. You’re not going anywhere; you’re just taking in what interests you. Follow your whim. Observe that tree with the golden leaves—is it a ginkgo? Do you smell that mud? It reminds you of the creek you played in when you were little. That house seems abandoned. What’s its story? The key is to observe and daydream. Let new sights enter your heart and activate feelings.

“The key is to observe and daydream.”

Another way to familiarize the strange is creating an atlas of weird things in your vicinity, from contorted tree trunks, to old pipes that seem to spring from nowhere, to spooky graffiti, or that underpass that’s always cold as hell.

Still another method: create a shadowbox. Over a week, pick up the strangest small things you come across. Maybe an interesting piece of litter. Perhaps a penny. A cicada husk? A crocus? Then turn a shoebox on its side and glue these objects into the configurations of your choosing. Now look at it as you would a stage in a theater. What does the scene tell you about yourself?

Try this, too: look at some medieval maps. See all the absurd monsters, strange coordinates, and bizarre symbols? Draw a similar kind of map—not of a landscape, but of your heart.

3. Shock yourself out of your tired habits.

Sometimes our attempts to defamiliarize the familiar just don’t work because our habits are too deeply ingrained. Your front yard is just your front yard, not a springboard flinging your mind to the heavens, and the abandoned part of the city is just too dilapidated. When our old identity is blocking our ability to enjoy strange and exhilarating experiences, we need to startle it out of complacency.

One way to do this: wake yourself up from a brief nap. Scientists have shown that when the brain has just fallen asleep it remains loosely conscious of subconscious currents. If we awaken when our brain is in this state, we often experience fresh associations, bizarre visions, and startling insights. Salvador Dalí knew this. He napped in a chair with a key between forefinger and thumb. As he relaxed into sleep, the key dropped onto a metal plate on the floor, and half-woke him into his surrealistic visions. You can do a variation on Dalí, using a ball bearing or a handful of pennies. Whatever your technique for inducing half-wakefulness, keep a paper and pen beside you. The instant you awaken, write down what you are thinking or feeling. Something fresh and ecstatic might emerge.

“When our old identity is blocking our ability to enjoy strange and exhilarating experiences, we need to startle it out of complacency.”

Another way to surprise yourself is opening a book to a random page and pointing. What word does your finger light on? Write it down. Do this four more times. Turn your five words into a poem about yourself.

Yet another way to startle yourself: Stare at your face in the mirror for five minutes.

4. Turn something into something else.

Artist M. C. Escher asked, “Are you sure that a floor cannot also be a ceiling?” Marcel Duchamp, another artist, turned a urinal into a fountain. We can liberate objects from their traditional uses, and thrill to the enchantment: you can turn anything into virtually anything.

Start small. Take a paper clip. What else can you bend it into? A hook, a key ring, an un-clogger of glue containers, the letter “L,” a bracelet, or a thin metallic worm. Then there is this story: “A Zen master pointed to a fan and asked two monks what it was. The first monk picked it up and fanned himself silently…The other monk took the fan, placed a tea cake on it, and offered it to the master. The fan was now a serving tray. This is the emptiness of the fan.” This means there is no such thing as “fan-ness,” just as there is no such thing as “paper-clip-ness.” These are ghostly concepts that attempt to fix an object onto one meaning. But in reality, a thing is less a noun and more a verb; not so much a solid as a likelihood.

Practice turning an object into an action. Grab a book. What can you make it? Maybe a tray, a plinth, a rectangular fluttering frisbee, a weapon, a shovel that works only in the loosest of sand, something to spin on your index finger, a tiny platform that makes you a little taller, a plate for potato chips, a triangle or a dollhouse, a measure of your posture, an example of a rectangle. Scientists say such transmogrifying improves creativity. It also softens facts into fantasies.

5. Embrace those parts of yourself you’re afraid of.

Great creators have made the weird their work. The eccentric artist is a cliché, but not an inaccurate one. Truman Capote feared planes with two nuns on board and avoided rooms containing yellow roses. Monkeys, peacocks, a bear, a crane, and a crocodile were the pets of Lord Byron, who imbibed wine from skulls. Charles Dickens stuffed the paw of his dead cat Bob and affixed it to an ivory letter opener. Poet Gérard de Nerval walked a lobster on a leash. Einstein gathered cigarette butts and smoked them in his pipe. Enamored of oxidization, Dalí peed on the brass bands of fountain pens. To finish The Hunchback of Notre Dame on time, Victor Hugo locked himself in his room naked. Steve Jobs ate so many carrots his skin turned orange. Buckminster Fuller, architect of the geodesic dome, wore three watches, slept only two hours a day, and updated his diary every fifteen minutes. Maya Angelou wrote best in hotel rooms, from 6:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m.; she required that the sheets never be cleaned and that sherry, playing cards, and a Bible always be on hand. Yayoi Kusama, artist of infinite mirrors, chooses to live in an asylum and paint her world in polka dots.

“If you crave originality, then cultivate the strange.”

Geniuses tend to be weird because they embrace those parts of themselves that separate them from the masses. If you crave originality, then cultivate the strange. This is not easy. Go singular, and you risk being misunderstood, feared, disliked, or ignored. But without this gamble, how will you discover your power?

Here are some things you can do to express your inner weird. If your soul were an animal, what creature would it be? Tomorrow, on three occasions, do something you think your animal would. Another exercise: If you died tomorrow but still got to write your obituary, what would you write? Still another: Make up your own curse word. Or maybe paint odd messages on stones and secretly place them around your town.

Strange activities stimulate your weirdness muscles and inspire you to embrace what is other, and perhaps delightful, about you.

If exercises like these don’t cultivate creativity, self-knowledge, and empathy, then at least they will distract you. Since boredom is, according to Søren Kierkegaard, the “despairing refusal to be oneself,” it is good to be distracted. It is better, though, to be enchanted, to divine that the days are strange and around the corner is always another wonder.

To listen to the audio version read by author Eric G. Wilson, download the Next Big Idea App today: