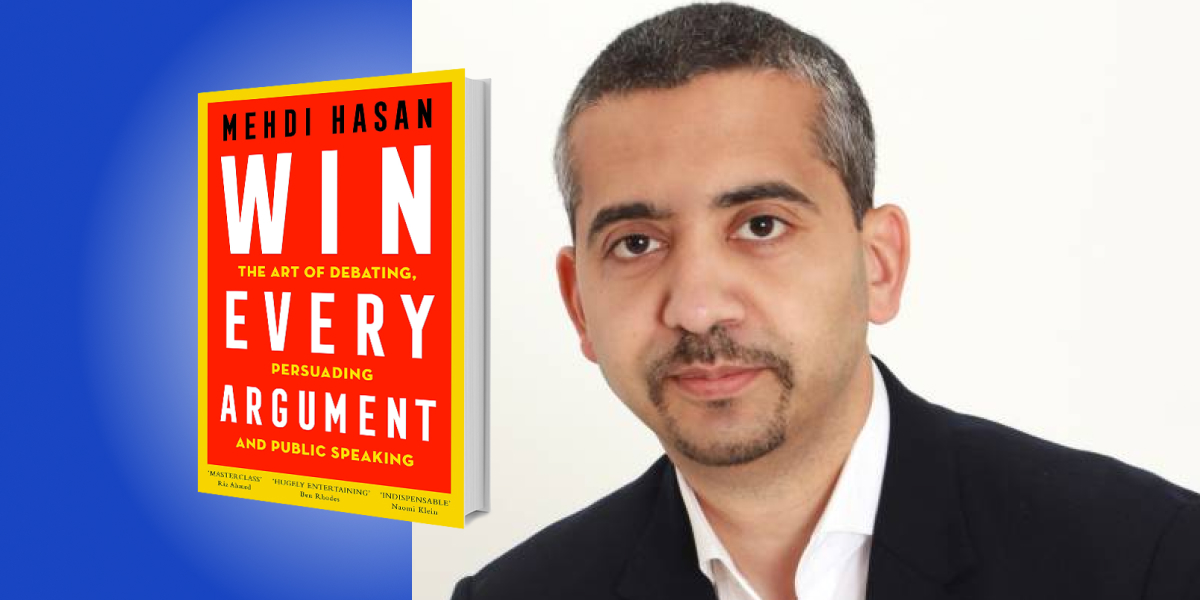

Mehdi Hasan is an award-winning journalist and the host of The Mehdi Hasan Show on MSNBC. He has argued with presidents and prime ministers, celebrities and activists, from across the globe.

Below, Mehdi shares five key insights from his new book, Win Every Argument: The Art of Debating, Persuading, and Public Speaking. Listen to the audio version—read by Mehdi himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Feel your way to victory.

I think it was Ben Shapiro, the conservative pundit, who popularized the phrase “facts don’t care about your feelings.” But what about the reverse? What if our feelings don’t care about the facts? Author Dale Carnegie famously described human beings not as “creatures of logic” but as “creatures of emotion.”

We often feel, rather than think or deduce, our way toward a particular viewpoint. Scientists say that some of our biggest and best decisions involve a jolt of emotion. Human beings, to quote Professor Antonio Damasio, the acclaimed neuroscientist, are basically “feeling machines that think.” To get people off the fence and on your side, you have to make an emotional appeal. You have to focus on what Aristotle called pathos.

To do that you have to use language that engages with their emotions; you have to be willing to show your own emotions, your passion for the argument; and, above all else, you have to be able to tell stories. As Plato is said to have remarked: “Those who tell stories rule society.” We, humans, love a great narrative. The human brain is hardwired, say experts, not for long lists of facts, but for storytelling.

To win an argument you need good anecdotes and gripping narratives to connect with your audience and get your points across. As Wharton professor of marketing and psychology, Deborah Small explained to me, stories that “are concrete (rather than abstract), personal, and narrative in form tend to evoke more emotion.”

Facts matter, but feelings matter more. If you win their hearts…you win their heads.

2. Play the ball…and the man.

When I was a kid playing soccer in school, the coach made it very clear: you don’t go after the player who has the ball, only the ball itself. You tackle the player and that’s a foul. So, you play the ball, not the man, as the saying goes.

When I got to college and started debating, I was told the same thing: go after the argument of your opponent, not the opponent themselves. Personal attacks are off-limits. Ad hominem arguments, or arguments literally “to the person,” are a big no-no. They are considered logical fallacies.

“You have every right to go ad hominem if they’re going ad hominem.”

The problem is, as Aristotle explained more than two thousand years ago, that audiences place a great deal of value on the “ethos” of a speaker: their personal character and credibility. Their standing, their expertise, their qualifications, that stuff makes a difference when it comes to whether or not people are willing to be convinced, so you have to be willing to question or undermine your opponent’s credibility.

It might feel a little icky to challenge your opponent so directly, so personally, but sometimes it has to be done. I’m not asking you to emulate the legendary Roman orator and debater Cicero who would hurl vicious invective at his opponents, calling them names, Trump-style, making fun of not just their arguments but their appearances, too.

I’m not telling you to do that. What I am saying is, for example, if a medical professional is making a bad argument but saying Trust me, I’m a doctor, you have every right to challenge their medical qualifications, their record as a doctor, their past history of claims or predictions; you have every right to go ad hominem if they’re going ad hominem. The same applies to conflicts of interest. If the guy opposite you denying climate change is funded by fossil fuel companies, why would you not bring that up?

The worst-kept secret in the world of debate is that arguments “to the person” can be both legitimate and effective. Don’t be a sucker. Don’t be a loser. Don’t ignore the power of a good “ad hom.”

3. Don’t be afraid to concede.

Sometimes you’re having an argument and they make a brilliant point. Perhaps something you hadn’t considered or anticipated. Perhaps something you have no response for. And yet rather than concede that point, you double down. You dig in. You refuse to budge.

Don’t. Do. That. Don’t be afraid to concede from time to time. In fact, it can actually give you the upper hand in a debate by catching your opponent off guard. The ancient Greeks called it synchoresis—basically, conceding a point so you can come back later with a stronger point.

“In fact, it can actually give you the upper hand in a debate by catching your opponent off guard.”

It’s a bit like judo, which is derived from the Japanese word meaning “flexible” or “yielding.” In judo, you’re not trying to use kicks or punches to knock your opponent to the ground. You’re trying to yield here or there, to unbalance them; to use their energy against them; to throw them down, ideally, when they least expect it. So, you can concede a point here or there to throw an unsuspecting debate opponent off balance. You can surprise them by pre-empting their points. You can even reframe the argument in your favor whenever you get the chance, again, leaving your opponent floundering. These are all rhetorical judo moves. To quote Kanō Jigorō, the founder of judo: “Resisting a more powerful opponent will result in your defeat, whilst adjusting to and evading your opponent’s attack will cause him to lose his balance, his power will be reduced, and you will defeat him.”

4. The rule of three is your friend.

Whether I am arguing with a politician over Middle East policy or arguing with my kid over how much ice cream they can have for dessert, I always try to have three main points. Three killer arguments. A, B, C. One, two, three.

What’s called the rule of three can be central to making a good argument. Think of those famous lines of political rhetoric from human history: liberté, égalité, fraternité—the French national motto. Or life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, from the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Or Abraham Lincoln’s government of the people, by the people, for the people. Those lines have impact. Those lines change hearts and minds because when you put your argument forward in three parts it sticks in people’s heads and even inspires. Cognitive psychologist Nelson Cowan told me that our working memory can basically “remember up to three basic units or chunks or ideas at once.”

Make sure you have three main points, and make sure you have a beginning, middle, and end—because three also gives you what Cowan calls a “stable structure.” It helps organize your arguments in a way that people find easy to absorb, remember and, ideally, agree with.

You cannot afford to forget or ignore the rule of three. As people have pointed out for years, it covers it all: from birth, life, and death, to past, present, and future. Once you master it, the rule of three will have you winning arguments left, right, and center.

5. Be prepared.

Too many of us start a rhetorical and very public fight without being prepared for it, without having researched our arguments or practiced delivering them out loud. There is a weird laziness when it comes to making arguments. We’re either overconfident and we think we can wing it, or we lack confidence and think we’ll never have what it takes to win over a crowd.

“You cannot engage in any kind of public speaking without the right amount and type of preparation.”

You cannot win an argument if you’re not ready for that argument. You cannot engage in any kind of public speaking without the right amount and type of preparation. The reality is that the best debaters and orators in human history had to do the grunt work; put in the hours; practice, practice, practice! Go back to ancient Greece and the great statesman Demosthenes, whom Cicero called the “perfect orator.” But as a young man, Demosthenes was a dreadful speaker and ended up retreating into an underground lair, Batman-style, for months at a time, to work on his voice and delivery. He even shaved the hair off half of his head so that he’d be too embarrassed to go outside.

More recently, in the 20th century, there was the young Winston Churchill who froze mid-sentence in the middle of a memorized speech to the House of Commons, unable to complete his thought. He was completely, utterly, and publicly humiliated that day. But Churchill never let it happen again. He practiced aloud while walking in the street; he practiced in private while sitting in his bathtub. He began keeping copious typewritten notes in front of him whenever he spoke in public or debated in Parliament. Nothing wrong with using notes! That can be a key part of the preparation and delivery process.

Don’t cut corners. “Give me six hours to chop down a tree,” that great orator, President Abraham Lincoln, is said to have once remarked, “and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.” Spend all the time it takes to sharpen your axe, to sharpen your arguments. And make sure you hone your delivery—the way you look, the way you sound, the way you stand —until it’s as sharp as can be. It all counts, and you can never ever be too prepared.

To listen to the audio version read by author Mehdi Hasan, download the Next Big Idea App today: