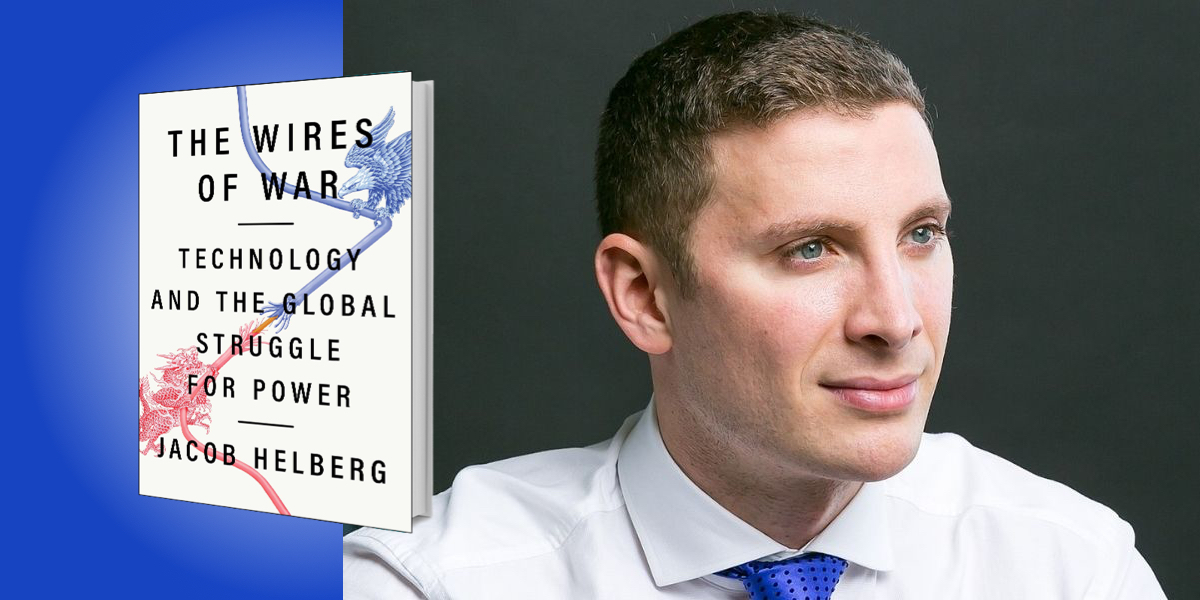

Jacob Helberg is a senior adviser at the Stanford University Center on Geopolitics and Technology and an adjunct fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He co-chairs the Brookings Institution China Strategy Working Group, which is helping support and lead research efforts focused on China’s intentions, foreign policy, and what the right long-term U.S. strategy should be to meet the challenge. From 2016 to 2020, Helberg led Google’s internal global product policy efforts to combat disinformation and foreign interference.

Below, Jacob shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for Power. Listen to the audio version—read by Jacob himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The Gray War is redefining international politics.

With the global economy more connected and intertwined than at any point since World War II, the costs and risks of an overt international war would be so damaging that the most powerful nations in the world have been deterred from engaging in a direct military conflict. But that doesn’t mean that geopolitical struggles for power have stopped. After all, war and peace have never been binary, and have always been a spectrum. What we’re seeing today is that great powers are increasingly subverting and leveraging technologies that make up our everyday lives to advance their interests and weaken their adversaries in the ambiguous gray zone between war and peace, competing over trade routes and fiber optic internet cables.

Gray zone competition conflicts are now a pervasive and predominant feature of international politics. I use the term “Gray War” to describe the systemic global tech-fueled struggle between U.S.-led democracies and China-led autocracies. The stakes of this war are ultimately about political power and influence over every meaningful aspect of our everyday lives, our economy, our infrastructure, our ability to compete and innovate, our personal privacy, and subtle decisions we make based on information we interact with every single day.

“Great powers are increasingly subverting and leveraging technologies that make up our everyday lives to advance their interests and weaken their adversaries in the ambiguous gray zone between war and peace.”

2. The new weapons of war are everyday technologies.

Unlike in the days of the Cold War, today’s new tech-fueled Gray War is primarily fought with dual-use technologies developed by private companies for civilian purposes. The reason has to do with the inverse relationship between the degree of destructiveness of a technology and its rational usability. For example, as Hans Morgenthau pointed out, a nation armed with nothing but high-yield nuclear weapons has no military means to impose its will on another country aside from threatening it with total destruction. Now compare that with commercial civilian dual-use technologies like artificial intelligence, 5G, and drones that can carry out high-impact attacks against an adversary in a way that is often far harder to attribute than attacks carried out with conventional weapons.

The result of these new technologies is that an aggressor often has the ability to deny its involvement in an attack and reduce the risks of costly retaliation. In other words, it’s because they’re effective and far less risky for aggressors that commercial dual-use technologies have become highly usable forms of weapons. Governments can deploy them for the daily conduct of strategic affairs in a way that doesn’t trigger a significant cost to themselves or their population. And that’s exactly why we’re seeing them doing it. I call this the “usability-destructiveness paradox” of modern warfare.

3. The face of censorship has fundamentally changed.

In the era of newsfeeds, modern-day censorship is no longer simply about whether information is in or out—it’s about whether it’s up or down. Autocrats distort what internet users see in their feeds by using two broad tactics: firehosing and information laundering.

“Modern-day censorship is no longer simply about whether information is in or out—it’s about whether it’s up or down.”

Firehosing entails artificially pumping so much information onto the internet around a particular topic that it drowns out everything else published on that topic. In doing so, autocrats can artificially suppress content written by others, and the content that autocrats don’t like becomes harder to see and access by everyday internet users.

Information laundering is when an autocratic government publishes and artificially amplifies stories to the detriment of other content around the same subject. This tactic usually aims to exploit online virality in order to bring fringe narratives into more mainstream forums.

Both methods amount to different ways of artificially distorting the information that internet users can see, resulting in the suppression of one type of content and the promotion of another. This marks a fundamentally new and different censorship paradigm than the old paradigm of simply blocking or banning access to information.

4. Old conceptions of sovereignty no longer apply.

The CIA estimates that the Chinese government has subsidized the telecom giant Huawei to the tune of 75 billion dollars. Observers around the world initially assumed that the motives of the Chinese government for these subsidies were primarily commercial and economic. But more recently, we’ve seen that there are also important political implications. For example, a newly disclosed 2010 risk assessment commissioned by KPN, a large Dutch telecommunications company, showed that Huawei can have completely unfettered access to everything that runs on top of its network, including all conversations and telephone numbers of political leaders and intelligence officers.

“Political control is no longer just determined by boots on the ground—it’s determined by wires in the ground.”

What that says is that control of the internet at the hardware level can effectively allow a government to access, block, and manipulate any data that runs on top of it. In a Gray War environment, control is power, and infrastructure is control. This creates a fundamental challenge to our traditional conceptions of national sovereignty. Political control is no longer just determined by boots on the ground—it’s determined by wires in the ground. Just imagine, as Yuval Noah Harari once asked, what might happen if a foreign adversary government knew the entire medical and personal history of every politician, every judge, and every journalist, including all of their sexual escapades, their mental weaknesses, and their corrupt dealings? When you control the wires in the ground, you no longer need to send soldiers on the ground.

5. In the Gray War, de-industrialization is disarmament.

In 2011, President Barack Obama attended an intimate dinner in Silicon Valley. At one point, he turned to Steve Jobs and asked, “What would it take for Apple to manufacture its iPhones in the United States instead of China?” Jobs responded, “Those jobs aren’t coming back.”

That response captured an assumption that runs through the American policy-making community, and has for a generation. But what if it’s wrong? As we’ve seen since the start of the pandemic, the weaponization of supply chains and information networks exposes the grave dangers of the de-industrialization that we’ve all accepted as inevitable. In this new Gray War, a de-industrialized United States is a disarmed United States. It’s a United States that’s precariously vulnerable to coercion, espionage, and foreign interference. If the U.S. is to secure its supply chains and information networks, it needs to re-industrialize. The question today is not whether America’s manufacturing jobs might be brought back, but whether America can afford not to bring them back.

To listen to the audio version read by Jacob Helberg, download the Next Big Idea App today: