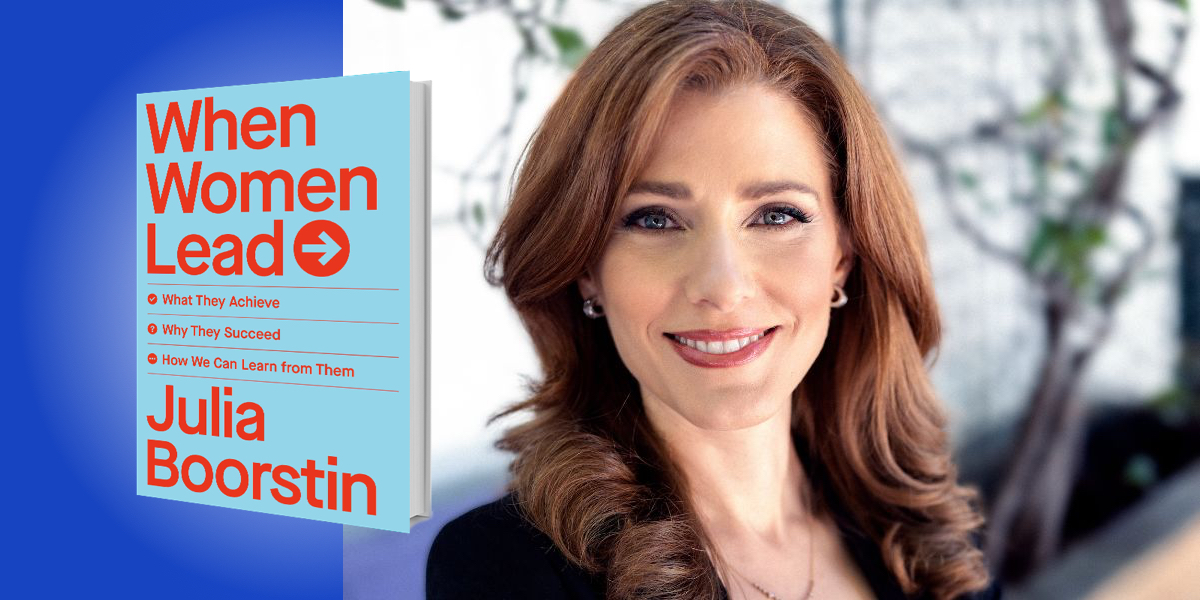

Julia Boorstin is CNBC’s Senior Media & Tech Correspondent and has worked for the network since 2006.

Below, Julia shares 5 key insights from her new book, When Women Lead: What They Achieve, Why They Succeed and How We Can Learn from Them. Listen to the audio version—read by Julia herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Superpowers don’t always look like powers.

There is no one type of leadership that always works, nor is there a singular trick to navigating challenges. There are stories from phenomenal women who were often wildly different from each other, whose successes were due to their complex and nuanced approaches to leadership. Their approaches looked nothing like those of a strident founder, visionary, and monomyth that have dominated in the business world for decades. In fact, female leaders who have tried to mimic the stereotypical male leadership styles have often failed, perhaps because of it. Elizabeth Holmes, for example, cast herself in Steve Jobs’ image—an aspiring Supergirl copying a Superman.

In the mainstream business world, there have been a handful of qualities traditionally associated with innovative leaders, especially in tech. Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk have unwavering confidence, inventing entirely new business categories and shooting rocket ships into space. Mark Zuckerberg has a move-fast-and-break-things message. Some women have qualities that would certainly not look out of place on a stereotypical male leader: Julie Wainwright is independent and persistent, Christine Hunziker is competitive. Another CEO, Katherine Power, who has founded numerous companies, makes it very clear she does not care about what other people think about her. There are also plenty of male leaders who show and benefit from more stereotypical female approaches.

Leadership superpowers often have nothing to do with power itself. There are characteristics, such as neurotic anxiety about planning ahead for worst case scenarios, that don’t scream confidence and unflappable leadership. But those same traits inspired Caryn Seidman-Becker, the CEO of Clear, to invest in long-term planning and also create situations to enable her to be adaptable.

Jennifer Holmgren is the CEO of a company called LanzaTech. She’s an introvert, a characteristic that has been described in many people as a flaw. For her, her preference to listen rather than speak made her a better negotiator because she could really understand where her counterpart was coming from. That range of characteristics, particularly those traditionally thought to betray weaknesses, can, in fact, be counterintuitive strengths.

“Leadership superpowers often have nothing to do with power itself.”

Toyin Ajayi, the CEO of Cityblock Health, slowed down and shifted the power dynamic away from her company’s team over to the patients. She put the patients in charge. Gwyneth Paltrow, the CEO of Goop, admitted she didn’t understand business jargon and that didn’t just help her, but gave her team permission to ask questions. Stitch Fix founder Katrina Lake was entirely forthright about her lack of experience in different areas, and that made her a talent magnet because that vulnerability invited other people to collaborate with her. The takeaway here is to look at your traits—don’t see them as flaws, as they can become your superpower.

2. Don’t fight the fear, acknowledge it.

You’ll often see older men running businesses and mutual funds who seem to have unwavering confidence. But the reality is that nobody is ever entirely sure of what’s going on. Everyone is just making the best decisions they can, with all the data they have at the moment. There are so many stories about confidence disconnects and feelings of imposter syndrome, but at the end of the day, it’s important to be honest about your lack of certainty. When you don’t feel confident, that can be a valuable tool; it’s an indication that you should be seeking information from other people.

In addition, expressing a lack of confidence can signal vulnerability and invite trust. Leaders are more successful when they are not self-confident all the time, when they admit when they don’t know all the answers, and they use those moments to invite collaboration from employees and team members from across their organization. After gathering the most diverse perspectives and insights possible, they formulate their solution, turn their confidence back up, and execute.

Acknowledging anxiety or fear is a sign that you should be going out and doing more homework. Use that homework to build your confidence back up. A balance of self-confidence and humility is essential for a growth mindset and valuable for any leader.

3. Don’t avoid dwelling on your obstacles, understand them.

Really dig into the data about bias and stereotype and how it impacts people. Through digging in, you can see that understanding these forces, no matter how grim they seem, can be a valuable tool to help people circumnavigate them. It’s much harder to achieve equity when we don’t realize just how far from it we currently are. It’s much harder to manage or neutralize double standards if you don’t see them.

“If you know how big the mountain is, you can figure out how to climb it.”

Acknowledging a challenging situation is not admitting weakness or defeat, it’s another form of preparation, and a key step in helping to accomplish meaningful change. If women who are fundraising know that the questions posed to them will likely focus more on their businesses’ downside risks, then they can anticipate how to reframe the conversation into a discussion about their company’s upside potential. Those are the questions that their male counterparts are asked.

If women know that their team will doubt and question them if they show anger, they might find different modes of expression. Kim Taylor, the CEO of a company called Cluster, was wary about backlash for delivering negative feedback. She developed a strategy to work around that, to delegate those notes to male managers. Don’t believe in the serenity prayer, believe in understanding the things which you cannot control. You shouldn’t spend time dwelling on them, but if you understand them, you can get around them. If you know how big the mountain is, you can figure out how to climb it.

4. It takes a village—a diverse one.

Of 120 women interviewed for my book, all of them stated that no matter how much credit they deserved for founding their company, taking on risks, and doing things that many people would think impossible, it was essential to acknowledge the contributions that other people made to their success. Whether it was a team collaborating to build a company or a C-suite coming together to pitch their startup to investors; nobody succeeds alone.

The most successful leaders are not those working alone as visionaries in an office, but those who are able to draw the most out of their teams. Study after study has found that the smartest teams are diverse, not just in terms of gender, but also in terms of race, backgrounds, and viewpoints. There is an advantage of communal leadership—leading not with a top-down approach, but communally, bringing together perspectives from across an organization. Although this is a style associated with women, strategic collaboration is not a stereotypically feminine, warm and nurturing welcoming of ideas—bringing together diverse perspectives is, in fact, about embracing the discomfort that can come when outsiders stimulate new perspectives.

There was a remarkable social science experiment done at Northwestern University about sorority and fraternity members who had an outsider join some of their groups. When an outsider joined them, the groups performed better at solving a test. They performed better not because a newcomer provided better ideas, but because the presence of a newcomer forced the original group members to reconsider their own perspective. If you dig into the data from the study, it shows that people are more sensitive to their own ideas and more conscious about their own contributions when they’re not surrounded by people just like them.

“Companies and organizations will be more successful if they figure out how to enable people to disagree.”

People step up their performance when they’re surrounded by people with other ideas and backgrounds. What’s most interesting here is that the students who were part of this experiment didn’t report that it felt good to reconsider their ideas. It felt challenging, but that feeling of difficulty meant that progress was being made. Communal leadership isn’t a kumbaya welcoming of ideas. It’s strategic work, drawing out opposing views and figuring out how to make a clash of perspectives result in a productive outcome. We need to lean into these challenging clashes of ideas. Companies and organizations will be more successful if they figure out how to enable people to disagree.

5. Nothing is more powerful than women helping one another.

There’s a stereotype that men are better at negotiating than women. A number of studies have found that the strongest negotiators are not men, however, but women negotiating on behalf of someone else. This indicates that women have been socialized not to push as hard when they’re speaking up for themselves. Hopefully women will start to change this as they come together. Organizations like All Raise and companies such as Chief and The Crew are teaching women to coach each other, and helping women unleash their negotiating ability and advocate for themselves.

They’re also creating the networks that are essential to help women succeed and making the bridge from these smaller, more nurturing female-dominated micro-environments into macro-environments. The stereotype that women are not kind to each other in business may have been true in the ’80s and ’90s. Back then, there was usually only one woman in the room, therefore there was little incentive to help each other or the next generation of women. Now the opposite is true. Women understand they will do better if they have other women around them.

Boardroom and executive suites are nearing a point of massive change. There’s a theory that once organizations hit what’s called a critical mass, about 30 percent, that’s key for a minority group to affect real change. At that point, a power dynamic starts to shift. We’re starting to see women hit that 30 percent mark in numerous organizations. Women are coming together and inspiring each other, helping each other unleash their professional potential.

To listen to the audio version read by author Julia Boorstin, download the Next Big Idea App today: