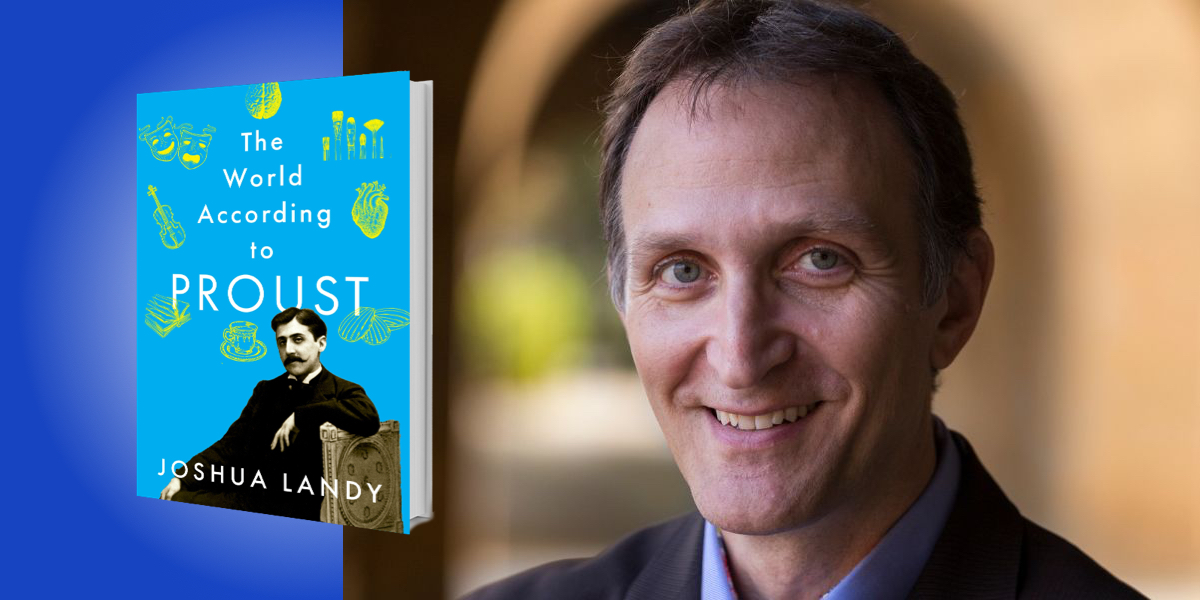

Joshua Landy teaches literature and philosophy at Stanford University. He is also co-director of the Literature and Philosophy Initiative at Stanford.

Below, Joshua shares 5 key insights from his new book, The World According to Proust. Listen to the audio version—read by Joshua himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Memory shows you who you are.

Try this: think about what you did on your last birthday. Who was there? What presents did you get? How did it go?

OK, now try this: pick a song you used to listen to a lot a long time ago, but you haven’t heard in years. Turn down the lights and listen to it. What comes back to you?

Whatever you remembered about your birthday party you remembered voluntarily: you deliberately called it to mind. But whatever you remembered thanks to the song—that popped into your head without trying. For instance, the time you made a fool of yourself at New Year’s thirty years ago in front of the person you most cared about while that song was playing. (That example may or may not be autobiographical).

“Proust loves this kind of memory—the involuntary kind—because it teleports you through time, dropping you straight into the shoes of your former self.”

A more famous example is the madeleine scene in Proust, where the main character eats a cake he hasn’t tasted in years, and suddenly remembers parts of his past he has long forgotten. At once, he says, “the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory”; “I had ceased now to feel mediocre, contingent, mortal.”

Proust loves this kind of memory—the involuntary kind—because it teleports you through time, dropping you straight into the shoes of your former self. You experience that person’s emotions from within: the joys, sorrows, and—in my case—humiliations. But more importantly, you notice a part of you that hasn’t changed: a way of seeing the world. That’s the thing that makes you, you.

2. It’s good to be a self.

In Proust’s novel, the lowest point for the main character comes when he feels shattered by grief and has lost all sense of who he is. He no longer feels, he says, like “an individual, identical, and permanent self.”

You want to be all three of those things. You want to have an individual self, rather than just blending into the crowd. You want to have an identical self, rather than being torn apart by competing impulses: Should I be with this person or that person? Should I take this job or that job? Should I eat the tofu burger or the chocolate mousse? (Trick question: the answer is chocolate mousse.)

And you want to have a permanent self, rather than changing wildly all the time. You need to be able to take responsibility for what you did in the past, keep your promises in the present, and make plans for the future. Sure, you shouldn’t get locked into a bad relationship or a bad job or a bad way of thinking—but your changes have to make sense and hang together in a story you can tell yourself about your life.

If you can have all of that, Proust thinks, you’ll make life better for yourself. You may even make life better for other people.

3. The world will thank you for sharing it.

At least if you share it in a poem, a painting, or a song.

“Art is a gift that fills the world with almost magical possibility.”

Here’s what Proust thinks about human beings: every single person has a different way of experiencing life, an inner world that you’ll never find twice. But most of the time, those worlds are trapped inside our heads. We talk to each other about ideas, or argue about sports and politics, and never realize the amazing richness and strangeness of each other’s unique perspective. Even if we get to know someone really well, Proust thinks, we don’t get a full sense of who they really are.

But art pulls off a kind of miracle. When you look at a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe, read a novel by Toni Morrison, or watch a movie by Charlie Kaufman, you get beamed straight into their world. Art isn’t a bunch of authors self-indulgently wallowing in the glory of their selves. Art is a gift that fills the world with almost magical possibility.

Thanks to art, there are multiple versions of reality at our disposal. We get an extra pair of eyes with every artist we encounter, and we can wander around looking at the world in an O’Keeffe way, a Morrison way, and a Kaufman way. “The one true voyage,” Proust’s narrator says, “would be to possess other eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others.” That’s what painters, composers, and writers allow us to do. “With people like these we really do fly from star to star.”

4. Sometimes it’s good to lie to yourself.

Deliberately lying to yourself might seem impossible—how can you get yourself to believe something you yourself know to be false? But it’s an everyday occurrence.

Let’s say you’re at the swimming pool and starting to get tired. You tell yourself, “just one more lap and then I’ll stop.” But you swim your lap and still feel OK, so you add one more after that.

If you keep on doing this day after day, soon you’ll come to realize that it isn’t necessarily your last lap. Yet you keep telling yourself that, and sort of believing it! It helps you to keep going. Deliberate self-deception works.

“It helps you to keep going.”

There’s a scene a bit like this in Proust, though the pool is replaced with an invitation to tea with a crush, and swimming is replaced with heroically saying no. It suggests that our minds are divided, that we can exploit this division for our own good, and that when it comes to matters of the heart—or the gym—truth is not always the most important thing.

5. These insights are not enough!

They’re not enough because you also need the novel they came in, because fiction isn’t just a fancy delivery mechanism for ideas. These days we’re told that the point of interesting fictions is to send messages, teach truths, reveal realities, and a host of synonyms all saying the same thing. Proust thought that this attitude was misguided and dangerous—if someone gets all their moral instruction from novels, they’re going to end up confused.

Since Proust practices what he preaches, his own novel does more than tell us what to think. It gives us a glimpse into Proust’s fascinating mind. It trains our brain: making us better at storing things away, thinking probabilistically, and better at thinking twice. Like a giant mirror held up to our face, it helps us to see ourselves.

If we’re lucky, we’ll come away from the long but amazing time spent reading it with a better sense of who we are. We’ll also be better at remembering, at weighing evidence, suspending judgment—and even at fooling ourselves.

To listen to the audio version read by author Joshua Landy, download the Next Big Idea App today: