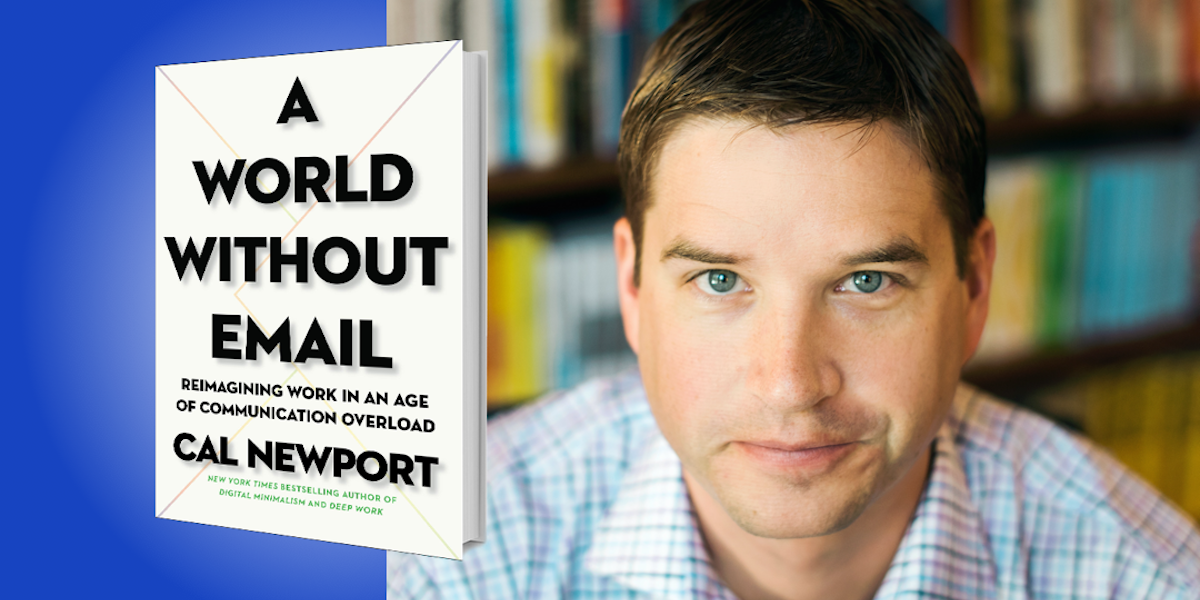

Cal Newport is the author of seven bestselling books, including Digital Minimalism and Deep Work. A frequent contributor to The New Yorker and WIRED, Newport is also a professor of computer science at Georgetown University.

Below, Cal shares 5 key insights from his new book, A World Without Email: Reimagining Work in an Age of Communication Overload (available now from Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to listen to the audio version—read by Cal himself—and enjoy Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Email makes us less productive.

Email spread quickly during the early 1990s because it was more productive than sending around paper memos in those folders with the little red thread ties. But as email moved from office to office, in its wake came an unexpected side effect, a new way of collaborating: the hyperactive hive-mind workflow.

Once we gained access to low-friction digital communication, we began to do most of our collaboration, coordination, and communication in unscheduled, ad-hoc, back-and-forth messaging. It’s fast, easy, and convenient. The downside, however, is that a ton of messages are generated each day. We have all of these unscheduled communication threads going, and they have to be tended.

The problem with this is every time we glance at our inboxes, we’re asking our brain to go through a cognitive context shift, and switching your cognitive context is an expensive neurological task. It takes time, but we don’t give it time. We glance at the inbox, we initiate a contact shift, but then we quickly rip our attention back to the main task we were working on. And we do this repeatedly throughout the day. The cost of all this aborted context shifting is that we lose our ability to think clearly. We begin to feel cognitive fatigue. That’s why by the time you get to two or three in the afternoon, you sort of give up on hard work altogether and just give in to your inbox. This is the hyperactive hive-mind workflow that email enabled. It is literally making us dumber—it is making it difficult for us to do serious thinking. And it is exhausting us.

2. Email makes us miserable.

Every moment that we spend not tending to our inboxes, we imagine they are filling up with messages from people we know, people we care about, people we respect—and they’re waiting for us to reply. This is a recipe for anxiety.

“If this makes us both unproductive and miserable, then maybe it’s time to look for better ways of collaborating in our digital age.”

The human brain takes social interactions very seriously because throughout most of our species’ history, carefully tending these one-on-one relationships could mean the difference between survival and death. This part of our brain can’t handle the idea that there are people who need us and we’re ignoring them.

Even when we know that those messages aren’t that important—it’s just Bob from accounting with an update!—that deeper part of our brain is not swayed by rationalizations. Just like telling yourself when you’re hungry that it’ll be lunch soon doesn’t stop your stomach from growling, no amount of rationalization about workplace etiquette can stop our social brain networks from flying into a panic the longer we leave our inbox unchecked.

3. Email has a mind of its own.

If the hyperactive hive mind makes us unproductive and unhappy, why did we decide to work this way? Well, it turns out no one did. There was no memo from management. There’s no Harvard Business Review article saying, “This is the new way to work.” It just happened.

When we recognize that the way we work is not intentional, it allows us to be much more critical. If the frantic way we communicate emerged at random, then we should be able to view it with enough critical distance to say: If this makes us both unproductive and miserable, then maybe it’s time to look for better ways of collaborating in our digital age.

4. Email overload cannot be solved in the inbox.

Once we recognize that it’s the underlying workflow that’s the problem, we see that we’re never going to solve it with better inbox habits or tips or etiquette, because the hyperactive hive mind demands your attention. You can’t do an email-free Friday if you use the hyperactive hive mind, because very little will get done on Friday. You can’t say “I’m going to check email twice a day” if your organization uses the hyperactive hive mind as its main way of collaborating, because people need you to check more than twice a day. All the decisions, all the task assignments, all the review, everything is happening through this back-and-forth messaging. So as long as the hive mind is in place as our primary tool for collaboration, we’re not going to fix it with better personal habits. We have to replace the hive mind itself with better ways of collaborating.

“A world without email is coming. The only question is whether you are going to be out in front of the trend or trailing behind it.”

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, but one metric that we need to focus on is reducing unscheduled messaging. Sometimes it’s simple—switching to a tool like x.ai or ScheduleOnce or Calendly gives you a way of setting up meetings with people that does not require many back-and-forth messages. It’s a great example of process optimization because you’ve reduced unscheduled messaging. Sometimes you need multiple different systems and tools to come together to optimize one of these processes. But remember, the goal is: How do we get this work done? And the answer is you work together to accomplish something while minimizing unscheduled messages.

5. A world without email is inevitable.

The great management theorist Peter Drucker, writing near the end of his life, observed that between 1900 and 1999, the industrial sector grew by 50 times. And they did it by constantly asking: What’s the best way to do what we do? The way they were building Model-Ts in 1921, for example, looked very different from the way Elon Musk builds Teslas in 2021. Drucker went on to say that modern knowledge work is where industrial work was in 1900. We’ve never tried to figure out the best way of doing things. In our current moment of digitally-enhanced knowledge work, we just came up with the first convenient way to engage in an age of networks—the hyperactive hive mind—and we gave everyone an email address and a Slack account.

We haven’t been critical. We haven’t been asking, “Is this working? Is there something better to do?” The good news, though, is that we are still in the early days of digitally enhanced knowledge work. There is so much growth on the table.

Achieving that growth means moving past the hive mind. That may be difficult at first, with significant upfront costs and minor inconveniences. But ultimately, we can increase productivity while decreasing burnout and turnover. A world without email, which is really a world without the hyperactive hive-mind workflow, is coming. The only question is whether you are going to be out in front of the trend or trailing behind it.

To listen to the audio version read by Cal Newport, and browse through hundreds of other Book Bites from leading writers and thinkers, download the Next Big Idea App today: