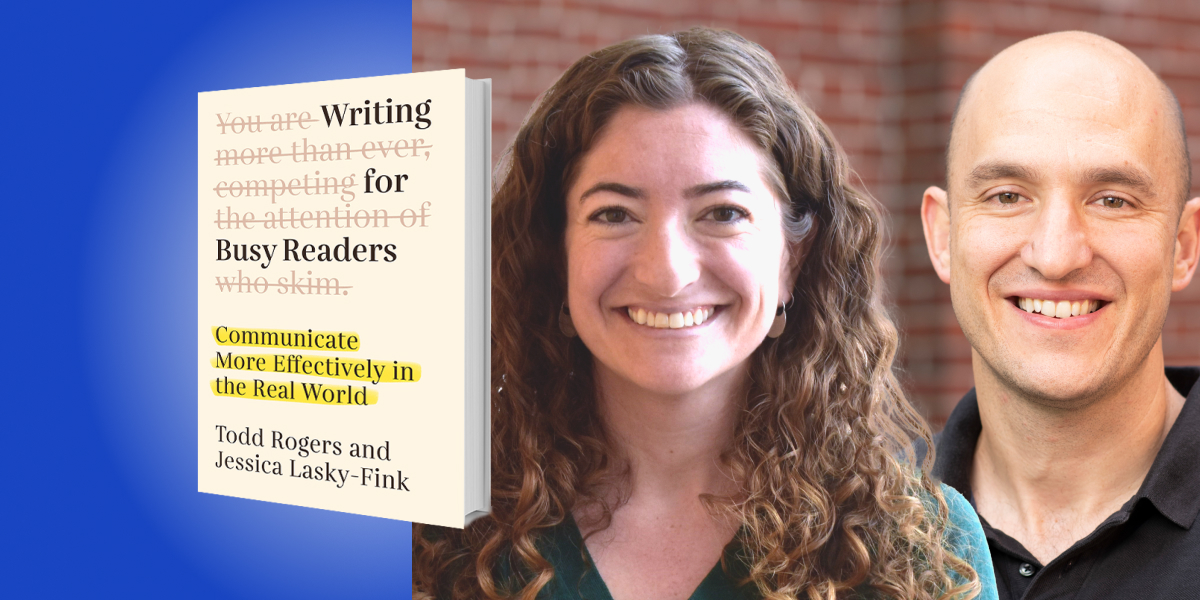

Todd Rogers is a behavioral scientist and Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. There, he is faculty director of the Behavioral Insights Group and director of the Student Social Support R&D Lab.

Jessica Lasky-Fink is the Research Director of The People Lab at Harvard, where much of her research centers on using behavioral science to optimize government services.

Below, co-authors Todd and Jessica share 5 key insights from their new book, Writing for Busy Readers: Communicate More Effectively in the Real World. Listen to the audio version—read Todd—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Everyone skims.

Think about how you “read” the last long email you received. You probably didn’t read it as closely as the sender had hoped. Our readers have better things to do than closely read what we write. That’s why they skim. A reader’s goal is often to move on to the next thing on their to-do list.

We writers usually care more about what we’re writing than our readers do. Far too often, that means readers move on without figuring out our main point. Research, where cameras track people’s eyes when they read, finds that people often quickly dart around text. They jump forward, skipping words, sentences, paragraphs, and even entire sections. They read some parts closely, then jump, sometimes even moving backward to figure out what they missed. If we want to be effective, we need to write for skimmers because everyone skims.

2. Write for navigation.

Our writing is more than a continuous string of words. It’s a visual scene that readers navigate, much like an image or a map. If we think of the challenge of writing effectively as partly a design problem, our approach changes. We create more white space, we incorporate clear organizational cues, and we use formatting and headings.

“It’s a visual scene that readers navigate, much like an image or a map.”

In a study we conducted, adding headings to a nine-paragraph message sent to 46,648 newsletter subscribers doubled the clicks on the lower part of the message, without reducing engagement with the initial paragraphs at all. Adding headings as navigational cues made the message easier for people to read.

3. Less is more.

When Blaise Pascal apologized in the introduction to a published letter, “I would have written a shorter letter if I had more time,” he made two subtle points. First, writing less can take more time. And second, writing more than needed calls for an apology.

More words than necessary demand more reader time than necessary. It’s an unkind tax. Strunk and White offered timeless advice in their book, The Elements of Style, that we should “omit needless words.” Yes, but it’s not just about eliminating useless words. It’s also about cutting down on only-kinda-useful words.

We sent two versions of an email to 7,002 school board members across the U.S., asking them to complete a survey. One version, 127 words long, began with several sentences expressing our gratitude for their important work. The other version, only 49 words, was more direct. When we asked a different group of people to read both, almost all of them predicted the longer one would produce more responses. However, the shorter email generated nearly twice the response rate.

4. Write simply.

Mark Twain famously advised, “Don’t use a five-dollar word when a fifty-cent word will do.” Though we don’t have to pay to write words, our readers pay for our words with their time and attention. When the price is too high, they move on to the next thing in their busy lives. Gratuitously sophisticated verbiage (ahem) can cognitively tax readers and discourage them from reading further.

More than that, fancy words can be hard to understand for a large fraction of people. According to the Literacy Project, around 50 percent of U.S. adults read at a 9th-grade level or below. Twenty percent of Americans read English as a second language. Untold numbers of people have learning challenges. To write in an accessible way, we should use short and common words whenever possible.

“Fancy words can be hard to understand for a large fraction of people.”

Consider the award-winning sign posted in a Canadian park that read, “Persons shall remove all excrement from pets.” The award, given by The Center for Plain Language, is more of a shaming than an honoring—it’s called the WTF Award (which, of course, stands for “Words That Failed”). Parkgoers likely didn’t bother to read the sign. Among those who did, many found it hard to decipher. A message is only as good as its ability to be understood: “Scoop Your Pet’s Poop” would probably have led to a cleaner park.

5. More effective is kinder and more inclusive.

Beautifully written or not, if a reader moves on from our writing before understanding the point, we have failed. Readers reward writers who make reading easy. They reward us by actually reading, understanding, and acting on what we write.

This isn’t just about being more effective. When we make reading easy, our words will get through to more readers and save them time. A project update that might have taken a client four minutes to read might now take one minute. That’s kinder. That’s more respectful. “Writing beautifully” is different than “writing effectively.” There’s a science to writing effectively and everyone is better off if we use it.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Todd Rogers, download the Next Big Idea App today: