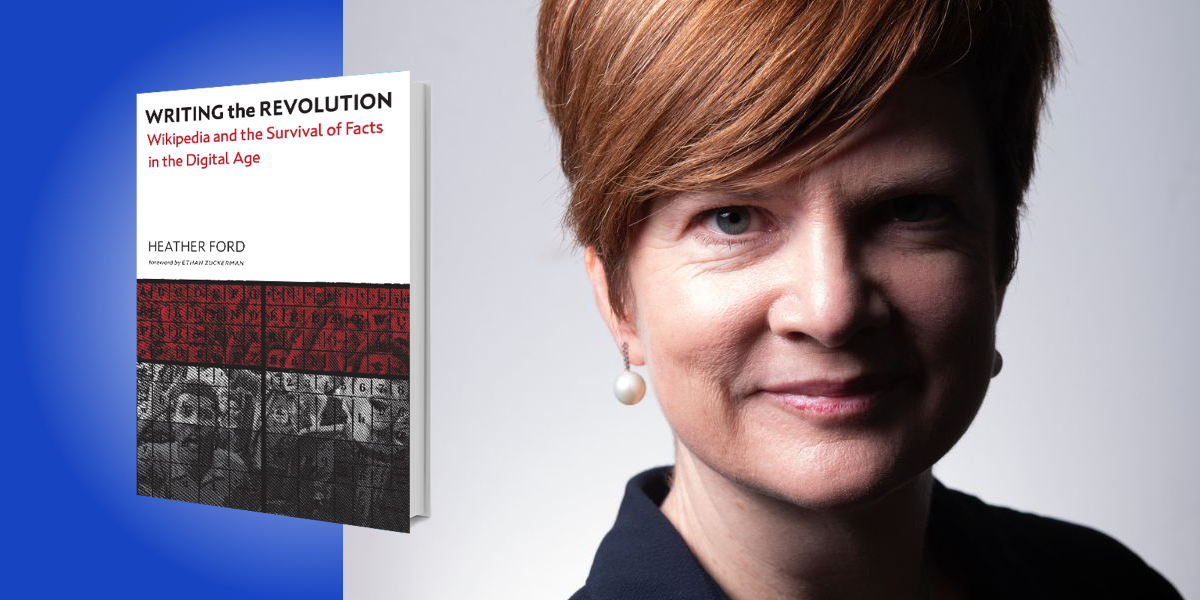

Heather Ford is a writer and academic who is interested in how digital technology shapes society. She has worked for tech non-profits like Creative Commons, APC and Ushahidi and has been a research fellow at Stanford University and the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Below, Heather shares 5 key insights from her new book, Writing the Revolution: Wikipedia and the Survival of Facts in the Digital Age. Listen to the audio version—read by Heather herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The first agent is the Wikipedian.

Unlike any previous encyclopedia, Wikipedia is a venue for knowledge about events that haven’t even finished happening. This has significant consequences for the ways in which history is written and who gets to write winning histories. In Writing the Revolution, I follow how facts about the 2011 Egyptian revolution were collected on English Wikipedia as events took place on the ground in Egypt during ten days between late January and early February 2011. Then I trace how those facts move between different places on Wikipedia and the wider Web.

The first agents to understand are the Wikipedians, who are volunteer editors dedicated to the long-term maintenance of the project. The Wikipedia editor who wrote the first version of the article about the Egyptian revolution prepared the article the day before the protests were scheduled on the 25th of January 2011. His username was The Egyptian Liberal and he was a young Egyptian democracy activist. Protests had been planned by democracy activists in the weeks prior to January 25, but no one knew whether anyone would actually show up on the day. In fact, major news outlets like the BBC predicted that Egypt would not follow Tunisia in major protests.

“The Wikipedia editor who wrote the first version of the article about the Egyptian revolution prepared the article the day before the protests were scheduled on the 25th of January 2011.”

The Egyptian Liberal wrote the first version of the article using an AFP source that had been published about the planned events. Wikipedia has policies that forbid creating articles about events before their historical importance is known or widely understood. Luckily for The Egyptian Liberal, he was soon joined by other editors that summarized journalistic articles after protests had begun. He gathered support by asking editors to continue to help building the article. He coordinated other volunteer editors on the talk page of the article (where editors discuss their changes). He did this obsessively right up to Mubarak’s resignation on February 11. Because he was one of the only regular editors on the ground in Egypt, The Egyptian Liberal was able to verify media reports. One example was when editors wanted to clarify who was the administrator of the Facebook group used to coordinate the protests. The Egyptian Liberal wrote, “I just spoke to Wael and no, he is still the admin of the page,” on the talk page on February 7th.

2. The second agent is the crowd.

You may be thinking: I knew it! Wikipedia is a place where anyone can write anything! But that’s rarely true. There are a lot of rules about what can be written on Wikipedia, and other agents that hamper Wikipedians’ ability to edit what they want. One such agent is the crowd. In addition to Wikipedians who are regularly updating the site and working intensively on articles, there are also crowds of newcomers who edit Wikipedia on waves of media attention. When a major event occurs, crowds of people from around the world move into the article to make history by making the historic edits.

In the case of the 2011 Egyptian revolution, the article saw multiple waves of new editors. When the announcement was finally made that Hosni Mubarak had resigned, the article saw its biggest crowds yet. Over 125,000 people visited the article on February 11. Wikipedians who had been studiously editing the article over the previous 10 days were suddenly overwhelmed by this crowd determined to the change the name of the article from “2011 Egyptian protests” to “2011 Egyptian revolution.” The crowd also tried repeatedly changing the date of the event to end on February 11. Some editors tried reverting the crowd’s edits because they wanted to be behind what secondary sources were saying rather than in front, but after only a few hours they gave up and the article’s name was changed to include “revolution.”

3. The third agent is the source.

Sources like books, scientific journals, and newspaper articles are critical to Wikipedia because one of the foundational rules of Wikipedia is that there is not supposed to be any original research. Everything on Wikipedia should be backed up by what Wikipedians call a “reliable source.” Wikipedians generally prefer peer reviewed academic books and articles to journalistic articles, and some newspapers like the Daily Mail in the UK are deemed unreliable. But in the case of breaking news, Wikipedians rely heavily on journalistic articles and these sources can remain hidden from the articles’ references after the news subsides.

“Sources like books, scientific journals, and newspaper articles are critical to Wikipedia because one of the foundational rules of Wikipedia is that there is not supposed to be any original research.”

Many of the editors I interviewed about the Egyptian protests article noted that their editing process began with watching live video of what was happening on the ground. Then they used Google to search for textual sources because video sources are difficult to cite since they are not always archived and are difficult to look up. Google was central to the Wikipedians’ research, and we know that Google prioritizes certain sources. Social media was central, too, because it was the main way that editors learned new information (even if those references didn’t stay on the article long). Al Jazeera English came to prominence during the revolution for the U.S. audiences in a way that it hadn’t been before. That’s because few major English news outlets had a presence in Egypt. There were few local sources because they would have been written in Arabic and very few of the lead editors were Arabic-speaking.

I found that the sources that Google prioritizes, as well as the live television coverage and social media, drive a particular understanding of what happens during catalytic events that is far from the academic books that Wikipedians would prefer to rely on.

4. The fourth agent is data.

Facts are digitized in Wikipedia, but they are also wrapped in metadata that explains to computers what kinds of entities are being described. I call this the packaging, for facts that travel through Wikipedia to reach search engines like Google and virtual assistants like Alexa.

Wikipedia has always been a source of datafied facts prioritized by the big platforms: Apple’s Siri, Microsoft’s Bing, Google Search and Home, and Amazon’s Alexa. But the year after the revolution, in 2012, Google launched an initiative that would further prioritize Wikipedia’s facts. It was called the knowledge graph and it resulted in a massive database of billions of facts extracted from Wikipedia and other public databases.

Data influenced how the revolution was remembered in two ways: first, it influenced how editors fought over facts on Wikipedia. Second, it influenced what became the consensus truth about what happened in Egypt in 2011. Wikipedia editors are aware that the data presented in their infoboxes are the most important elements of Wikipedia. Infoboxes are the little fact boxes on the right-hand side of most articles on Wikipedia that summarize the article. They also constitute the data that will be extracted by third parties, e.g. in Google, Bing, or Yahoo’s knowledge panels or fact boxes about the person, place, event or thing you’re searching for.

“Wikipedia editors are aware that the data presented in their infoboxes are the most important elements of Wikipedia.”

Within minutes of then-president Hosni Mubarak’s resignation, a massive crowd moved into the English Wikipedia article to change the name from protests to revolution, and to change the end date of the events to February 11. These are the datafied facts in Wikipedia articles that today form the stable facts presented by search engines in the right-hand fact box or knowledge panel and are used as virtual assistant answers. This information is critical because it is seen by many more people who generally view Google and results from other automated processes as somehow more truthful, more accurate, and more representative of the consensus of what happened than what would be found on Wikipedia—even when that is not the case.

5. The final agent is the event itself.

Without an event that tells a story that people want to hear (or at least people with power), then facts will not travel, stories will not be told, and historic events will not be recognized as such. In my ethnographic study of Wikipedia, I’ve analyzed many articles that have struggled to be born on English Wikipedia. These were articles by people written in my home continent of Africa about things (restaurants, cultural phenomena, political events) that faced significant challenges.

We already know that Wikipedia is written by a male majority (90 percent by some accounts). What is less well known is how difficult it is for people of color and people outside of North America and Western Europe to have their knowledge represented on English Wikipedia. Egypt was an anomaly. The event was the biggest news story in the U.S. in 2011. It captured the American imagination. It seemed to be a moment in the story of American democracy where platforms like Facebook and Twitter enabled the people to rise against their dictators.

In those two weeks between January and February of 2011, the world lit up by the excitement and fervor of what was happening in Egypt. It represented an ancient tale of the people rising against the tyrant, social media giving voice to the people, democracy spreading like a wave. Soon after Mubarak resigned, the crowd of Wikipedia editors moved on to other events and entities of interest. The article went relatively silent. The revolution was short lived and young people like my friend Alaa Abd El-Fattah are now in prison in Egypt because of their role in the events of 2011. Events can tell great stories but there are many more elements necessary for transforming governments and institutions.

To listen to the audio version read by author Heather Ford, download the Next Big Idea App today: