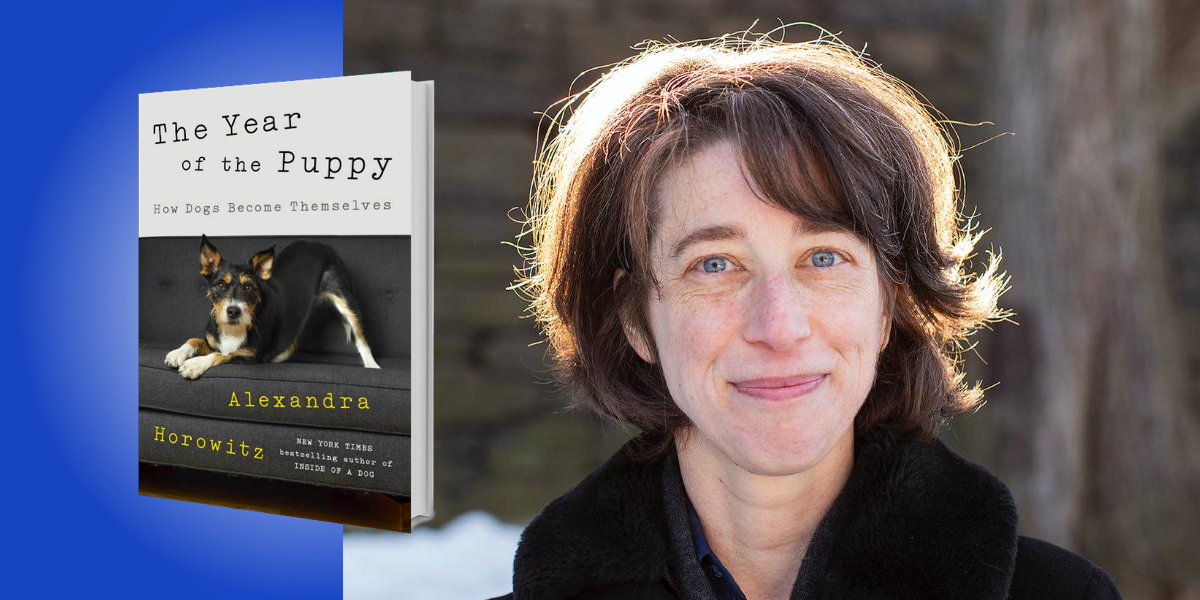

Alexandra Horowitz is a professor at Barnard College and Columbia University, where she teaches seminars in canine cognition. As Senior Research Fellow, she heads the Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard College.

Below, Alexandra shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Year of the Puppy: How Dogs Become Themselves. Listen to the audio version—read by Alexandra herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Embrace misbehavior.

Pick up a training book and you’ll probably read all about how to avoid your new puppy’s “misbehavior.” This is a mistake.

What is called “misbehavior” shouldn’t be understood as “bad behavior.” Instead, it is communication. It is information gathering. It is excitement, surprise, or even boredom. For instance, when barking at a guest, your puppy isn’t being rude. Your puppy is telling you something: someone is here, someone new! You are encouraging that behavior as you go right to the door, often barking back at them, albeit in your own way. Congratulations, you’re in conversation! Incidentally, wolves rarely bark, and it’s theorized that dogs began barking as a communication with us.

Information gathering is a dog sniffing you closely. Dogs see the world through their noses. Up close, they’re looking at you and finding out about you. Their noses have the acuity to tell where you’ve been, what you’ve eaten, and even if you’ve been secretly petting some other dog.

We tend to define dog misbehavior as those things they do that we simply do not like, regardless of whether the dog is equipped to understand or appreciate the rules they are breaking. Your dog’s “misbehavior” is telling you one thing, and it’s not that they’re bad dogs. What it’s telling you is how they experience the world differently than you do.

2. Your “puppy” is probably a teenager.

If you have a dog between six months and two years old, you do not have a “puppy.” You have a teenager. Though we think of dogs as either puppies or adults, they also go through a stage of adolescence. Just like the human teenager’s sometimes erratic behavior, teenaged dogs can be disobedient, appear to seek conflict, and then suddenly cling and stick by your side.

“Their brains are being re-wired, especially in areas that regulate emotions and make judgements.”

This phase in dogs is driven by hormones. Those hormones lead to sexual maturity that have other consequences, like increased sensitivity to touch and less self-control. Their brains are being re-wired, especially in areas that regulate emotions and make judgements. That is why you might see more challenges to your authority.

If an adolescent dog suddenly refuses to come when called, people are disposed to say they are a bad dog. This is a problem, because a primary reason for returning a dog is their behavior. They may jump, bite, escape, and soil the house. With the uptick of these behaviors in adolescence, there is a severe uptick of relinquishments, which can lead to euthanizing.

It is only a phase, however—and it’s hard for them, too. It’s been likened to waking up in a tent in a hurricane. Once you realize that, it’s easier to release your vise-grip and worry less about the mischievous scamp in your midst.

3. Dogs are not given a guidebook to living with humans.

New owners often pick up a training book to instruct them about their new pups. Where is the pup’s book, though? Surprisingly, we are that book. Dogs are not born understanding the byzantine rules of human social interaction, the rules of our houses, and what we consider appropriate behavior. Dogs don’t understand the pronouns we put on items—that’s my bed; that’s your bed. They don’t have a clue about the identities we give to objects—that’s a shoe, not a chew toy!

Research from the Dog Cognition lab at Barnard College has shown that even when we think dogs know they’ve done something wrong—giving the “guilty look” familiar to all dog people—this look isn’t a sign of guilt. It’s a learned submissive display they put on when we’re angry so we don’t punish them.

In our guidebook-writing way, we design their environment poorly, making it difficult for them to smoothly navigate a new space. You don’t leave kids alone with sharp objects, and we shouldn’t leave dogs alone with a cheese plate. If you leave a pair of your favorite shoes in the middle of the living room when you leave the house, you have designed the environment to include a special, you-smelling enrichment device at home. Your dog will take to it, and interact with your shoes in way that you might find objectionable.

“You don’t leave kids alone with sharp objects, and we shouldn’t leave dogs alone with a cheese plate.”

Sharpen up your tour guide skills, because you are leading your pup in a foreign land.

4. Your dog is your mirror.

Amazingly, there is research that bears out our intuition that dogs look like their owners, or vice versa. When given an array of photos of dogs, and another of people, it turns out that people can match the person to their dog at rates higher than chance.

They reflect us in other ways too. Their behavior shows us how we have dealt with them in the past. For instance, does your dog bark to go out? Do they start nibbling at you when they want attention? You have trained that. Dogs, coming into human homes not knowing the language, learn quickly to be good observers of your behavior. They try to communicate with you. As they do, the ways of talking that stick are the ones to which you respond. Do you ignore your dog when they’re quiet, and only look in to see what the matter is when they start barking? Your dog learns: bark to get your attention.

Take a look at your dog and you will start seeing something of yourself.

5. Lower your expectations to increase your chances of a satisfying relationship with a new dog.

This does not mean you should have no standards, that anything goes. But the expectations we tend to have upon meeting dogs and adding them to our lives often get in the way of learning about who they are.

“We come in thinking we know who a puppy is going to be.”

We have a lot of expectations. In today’s culture, puppies come to us, by breeder or shelter, with a reputation of their breed or parents already defining who they are: a “friendly” dog, a “trainable” dog, a dog that is “good with kids”. We look outside and see people walking down the street with dogs trotting agreeably by their sides. It looks as though it has always been that way. We see dogs coming when called, eliciting smiles from their person and wags all round.

We all come to the experience of having a puppy with ideas about how it’s going to go. We often idealize that it will go well right away. We come in thinking we know who a puppy is going to be. We prepare with books that talk about how puppies behave, similar to a user’s manual for our new tablet or coffee maker. We think it will be a sweet, innocent, easy addition in our lives. We think she will sleep through the night, will understand us, will want what we want. We’re wrong, of course. It is these expectations that distract us from seeing the delightful, difficult, burgeoning personality that is there.

Drop those expectations, and you get to watch them become who they are before your eyes.

To listen to the audio version read by author Alexandra Horowitz, download the Next Big Idea App today: