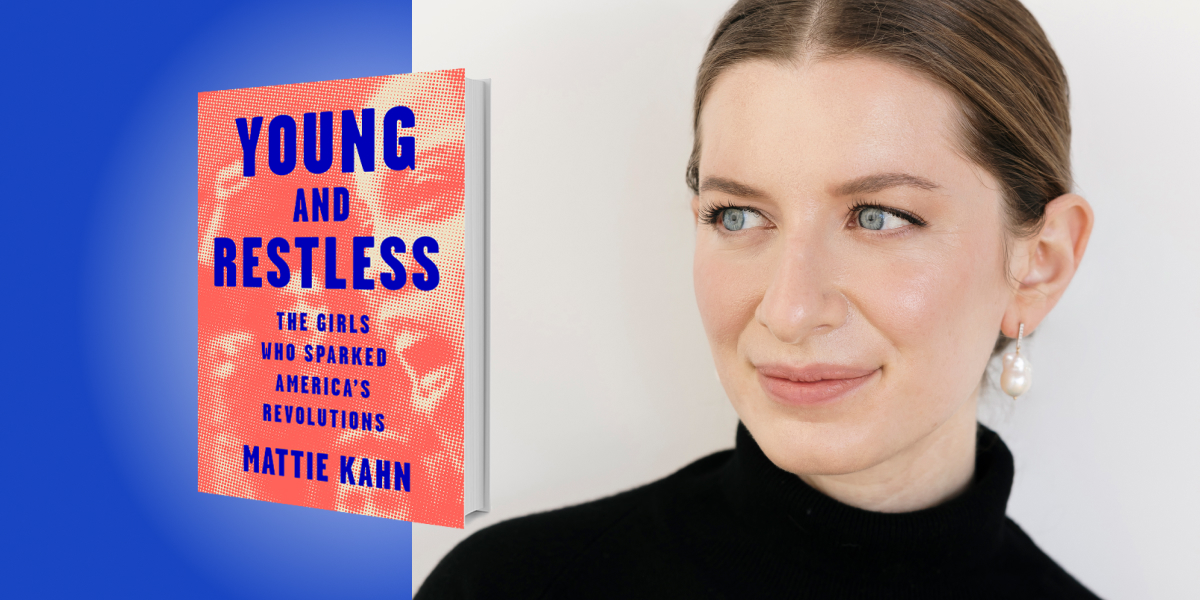

Mattie Kahn is an award-winning writer and editor whose work has been published in the New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Vox, and more. She was the culture director at Glamour, where she covered women’s issues and politics, and a staff editor at Elle.

Below, Mattie shares 5 key insights from her new book, Young and Restless: The Girls Who Sparked America’s Revolutions. Listen to the audio version—read by Mattie herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Look to your left and to your right: those are the people you’ll change the world with.

When we think about social change, we think about leaders: Martin Luther King, Gandhi, even Greta Thunberg, the climate activist who got her start as a teenage girl, demanding attention for the global warming crisis.

But students of social movements know that leaders don’t single-handedly mobilize some pliable flock of people. Efforts to realize change tend to start on the ground, among people who are experiencing injustice and sharing in a vision of what a better future could look like. From the Lowell Mill Girls, who protested working conditions in the 1830s, to the civil rights activists who risked their lives to desegregate schools and buses in the 1950s and 60s, the people who make change together are often friends, drawing on real relationships in order to build a movement. Friendship—or peer mentorship, as we might call it—is a potent, political force.

In 1960, a 16-year-old teenage girl named Brenda Travis got arrested after attempting to desegregate a bus station waiting room. She was sentenced to four months in jail for her so-called crime. When she was released, her principal expelled her because she’d missed the first month of school. No grownup swept in to fight for her, but her friends did. Over a hundred students walked out in protest. When the New York Times covered the event, it credited a field organizer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee named Bob Zellner with planning it. But Zellner knew he’d had no part. He’d been sitting in his office when the kids swept past him. He later quoted Gandhi: “There go my people, I have to go and run and catch up because I am their leader.”

Want to change the world? Don’t look to a man at a podium or a woman with a microphone. Look around you—those people on either side of you are your allies. They’ll take action. Your “leader” will follow.

2. No generation starts from scratch.

As I embarked on the project that would become this book, I thought I might keep my focus on this current generation of teenage girls—Gen Z. They’re at the forefront of the movement to address climate change and gun violence. They’ve organized marches for racial equality via Instagram DMs. Something seemed special to me about these girls, and I thought I might explore what made them so uniquely well-suited to protest and activism.

It didn’t take long for me to realize that teenagers have in fact been incredible organizers for centuries and that this generation was, of course, standing on the shoulders of those who came before them.

“But the true history of social progress is full of intergenerational partnership.”

There is a temptation to paint young people as one-dimensionally rebellious. Whatever their parents did, they won’t do. Whatever came before, they want to reject.

Again and again, that has been shown to be untrue. Yes, adolescents make their mark by individuating and sometimes that means pointing out what of the status quo needs to be disregarded. But the true history of social progress is full of intergenerational partnership. Young people bring energy and new ideas. Older people bring perspective and strategy. You don’t necessarily need both, but you’re better off with both.

In the 1910s, suffragists recruited young idealistic women to hand out fliers and march with banners at their parades. The older women wanted their movement to have an appealing face; girls provided it. In the 1960s, civil rights activists like Bernice Johnson—later Bernice Johnson Reagon—accepted hospitality from older folks who wanted to support their work, but couldn’t take their place on the frontlines. Johnson Reagon had once been dismissive of the role that grown men and women had in the movement, but she later wrote that she and her peers had not taken some quote-unquote unbelievable leap. It had been, as she put it, a continuance.

No activist needs to start from scratch. Appreciate the work that older people have done, and then put your own stamp on it. Don’t assume that there’s no infrastructure or precedent for what you want to accomplish. Do your research. Take what you can from what exists. Innovate.

3. Refine your message. Then refine it again.

I almost feel for the middle-aged Luddites who now have to do social media battle against Gen Z organizers who can run circles around them on the internet. In activism as in politics, communication is everything. You can’t win if you’re losing the message war. Young people know that, and they’re doing what generations of protestors have: using the medium du jour to their advantage.

Entrenched interests tend to have money, inertia, and accumulated influence on their side. But upstarts can claim a platform if they know how to use it.

During the Civil War, a gifted teenage orator named Anna Elizabeth Dickinson became a nationwide sensation for her fiery speeches. Adults could lecture too, but no one was braiding precociousness with wit and intellect quite like Dickinson. She became one of the most famous and best-compensated orators of her era.

“They’re doing what generations of protestors have: using the medium du jour to their advantage.”

Now the advantages of being a good communicator are even more obvious: The teenagers who are organizing for March for Our Lives are taking on the gun violence epidemic and their efforts helped lead to the first bipartisan piece of legislation on the issue in three decades. They run rhetorical circles around their political opponents. A college student named Olivia Julianna weaponized Twitter to raise over $700,000 for abortions after a congressman mocked her on the platform.

Distill what you want to say, and then keep distilling it. Your policy ideas don’t have to fit into a tweet, but your comebacks should.

4. Use disadvantages to your advantage.

One of the questions that this book hopes to answer is: What makes teenage girls such good and capable activists? How is it that in movement after movement, it’s girls who stand on the frontlines, risking it for progress?

In conversation with researchers and scholars, it becomes clear that the qualities that girls are socialized to develop make them skilled organizers. We raise girls to collaborate, to be articulate, to sacrifice for the greater good, to devote themselves to others, and to charm people. Think of what movement work requires! The Venn Diagram—as the kids say—is a circle.

In talking to successful and passionate activists from the civil rights movement to second-wave feminists to climate organizers, it has become clear to me that girls have always been savvy enough to use what is held against them to their advantage.

“The qualities that girls are socialized to develop make them skilled organizers.”

Second-wave feminists made consciousness-raising circles a centerpiece of their movement infrastructure, cannily creating space for the very thing that those who derided them accused them of wasting their time on: talking!

Youth organizers dismissed as being too online and dependent on their phones have built entire coalitions on the internet and across social media platforms. Generations of girls have marshaled what is used to discredit them in service of their ideals. The results speak for themselves.

5. Know your purpose.

Movement building is hard work; all progress is hard work. Losing sight of the reason you’re slogging through it is a recipe for infighting, distraction, and bad decision-making.

The opposite is also true: Knowing why you’re out there can drive you to persevere even in the face of unimaginable barriers.

Nine months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on that Montgomery bus, a teenager named Claudette Colvin was arrested for the same crime. She never became the face of the movement as Parks did. She ended up pregnant in high school and felt dismissed, not deemed the “appropriate” figurehead for the bus boycott, let alone the movement as a whole. Months later, activists were looking for plaintiffs in a case that would challenge this kind of discrimination on buses in court. They tried to recruit “upstanding” men—ministers, businessmen. But those people were afraid. In the end, four women stepped forward—and two of them were teenage girls. Claudette Colvin was one.

She had never been in it for fame or recognition. She knew what she was fighting for, and it brought her to testify under circumstances that made grown men quake.

These days, more people know who Colvin is, but few recognize her lasting contribution to the movement: her decision to be a plaintiff in Browder v. Gayle. Colvin’s life was hard, and the scrutiny to which she subjected herself didn’t make it easier, but she never forgot what she was fighting for. When it came time to step up, that awareness made all the difference.

To listen to the audio version read by author Mattie Kahn, download the Next Big Idea App today: