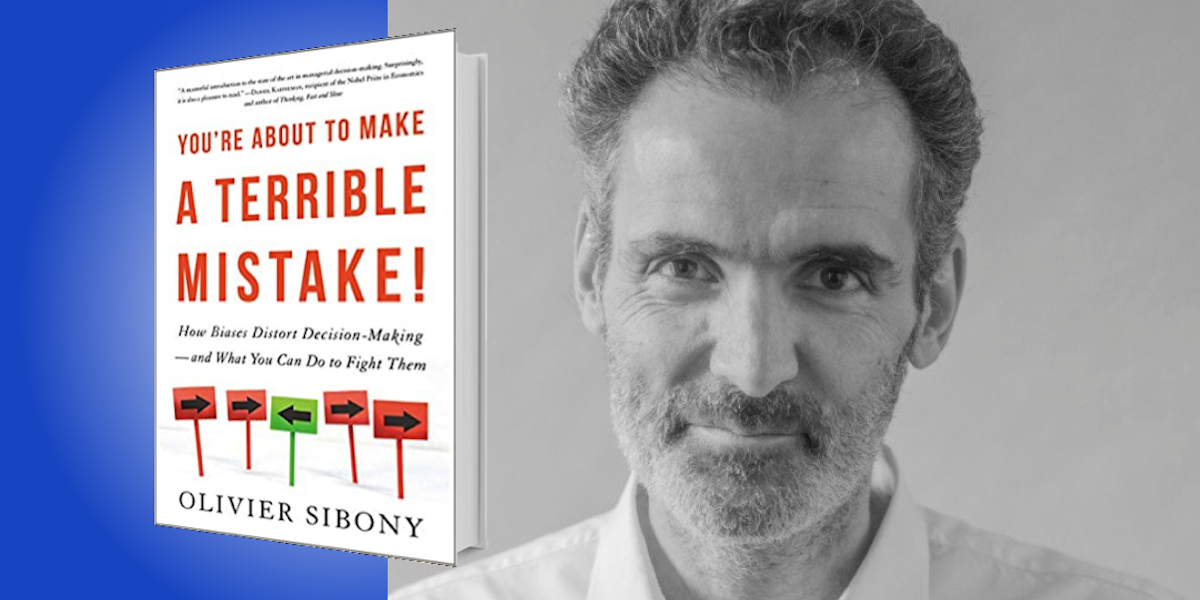

Olivier Sibony is an Affiliate Professor of Strategy at HEC Paris and an Associate Fellow at Saïd Business School, Oxford University. He also spent 25 years in the Paris and New York offices of McKinsey & Company, where he was a senior partner. Sibony’s research has been featured in Harvard Business Review, MIT Sloan Management Review, and more.

Below, Olivier shares 5 key insights from his new book, You’re About to Make a Terrible Mistake!: How Biases Distort Decision-Making—and What You Can Do to Fight Them. Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Learn the “reverse Anna Karenina” principle of strategic decisions.

Leo Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina famously begins, “All happy families are alike. Each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” For strategic decisions, it’s just the opposite; all great strategies are unique, but nearly all strategic mistakes fit one of a few typical patterns. For example, there’s the CEO who routinely underestimates risk in favor of gut feeling. There’s the organization facing disruption by a little startup that they can just ignore—until they can’t. And there’s the company that focuses on delivering great quarterly earnings, until it realizes that it has neglected to plan for the future. These all-too-common mistakes illustrate this “reverse Anna Karenina principle.”

2. It’s not about the CEO—it’s about you.

Why don’t the brightest executives learn from the mistakes that others have made before them? We often hear that a failed CEO was simply bad, or that they became a victim of their own hubris. But the truth lies in the cognitive biases that affect us all. For instance, some strategic mistakes happen because the CEO falls in love with his strategic vision, and doesn’t pay attention to the evidence that he’s on the wrong track. This is confirmation bias, and we’re all susceptible to it. There are also CEOs who pay too much attention to short-term results at the expense of the future—but the truth is, we all give too much weight to the short term.

3. Trust your gut—on the right stuff.

Our intuition is so powerful because it comes from our experience. When we recognize a situation we have encountered before, we can immediately assess the right decision, without even thinking about it. But since our intuition is the recognition of familiar situations, the more uncertain or unprecedented the situation, the less we should trust our intuition. So when making strategic decisions, first break down the decision into component parts. Then identify which specific parts are right for the use of intuition, and trust your gut with them. On the other, more novel parts, however, all your gut will give you is a false sense of confidence; the key is learning to recognize which parts are which.

“The more uncertain or unprecedented the situation, the less we should trust our intuition.”

4. Your job is not to be a psychic octopus.

During the 2010 FIFA World Cup, soccer fans discovered Paul, an octopus who correctly predicted the winner of eight games in a row. Paul may seem amazing, but hundreds or even thousands of animals around the world must have been trained to predict the results of World Cup games, so it’s no surprise that one of them happened to make lucky picks. In a similar fashion, we often evaluate leaders’ performance purely on results; we don’t stop to ask if they were lucky or unlucky. And the problem with this approach is that it discourages risk-taking. If you know you will be punished for bad outcomes, then it makes sense to refuse to take any risks, even when they are justified. So if we want people to take the right risks, we cannot evaluate their decisions based on their results—we need to focus on their process. Their job, and your job, is not to be a psychic octopus that gets the right results out of pure luck. It’s to make the best possible decisions despite uncertainty, and to prepare for the occasional failure that will not necessarily indicate a mistake.

5. A great team is nothing without a great process.

In 1961, President Kennedy approved a plan to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, and the expedition ended in disaster. The plan had been terrible, and even Kennedy knew it after the fact. 18 months later, Kennedy had to make a new set of decisions with the Cuban Missile Crisis. And as close as we came to World War III, he handled the situation with incredible skill. The difference was that after the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy realized that it wasn’t enough to surround himself with a brilliant team—he also needed to specify their process. For instance, he insisted that the team generate multiple alternatives to the plans that were initially suggested. He also asked two team members to play the role of devil’s advocate. Indeed, to improve the quality of your strategic decisions, it’s not enough to have a great team—you also need a great process.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: