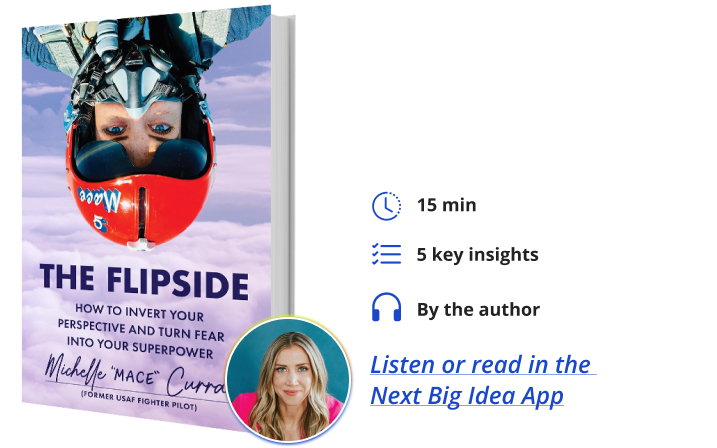

Below, Michelle “MACE” Curran shares five key insights from her new book, The Flipside: How to Invert Your Perspective and Turn Fear into Your Superpower.

Michelle spent over a decade as a fighter pilot and served as the Lead Solo Pilot for the Thunderbirds, the U.S. Air Force’s elite demonstration team. She has nearly 2,000 hours of F-16 flying time and flew combat missions in Afghanistan. Known for her upside-down maneuvers, she has inspired audiences at airshows and flyovers like the Super Bowl, Daytona 500, and Indy 500.

What’s the big idea?

Mace spent years operating in high pressure environments, from combat situations to performing high-speed maneuvers in front of millions of people. But what also came with that career were the moments behind the scenes of self-doubt, the struggle to find her identity, the near misses, and the mental battles that came with the job. Much of what she learned to persevere and triumph as a fighter pilot applies to winning at life.

1. Your inner critic is just a voice, not a verdict.

When I was a young, inexperienced fighter pilot, I lived with this constant fear that I didn’t belong and wasn’t good enough. I’d walk into a briefing room and feel like everyone else had it together. Meanwhile, I was hyperaware of everything I said and did as I tried to live up to my idea of what the perfect fighter pilot was.

This voice lives in all of us—that inner critic—telling you that you’re not ready, not enough, or don’t have what it takes. It may sound a whole lot like the truth, but that voice is often just fear in disguise: fear of being seen, fear of failing, or fear of finally succeeding and not knowing what to do with it. I had to learn that my inner critic wasn’t a signal to stop. It didn’t mean I was in the wrong place. It was a sign that I was pushing into something that mattered—something that was difficult, but worth doing.

I used to think that courage would show up, make me feel ready, and then I’d act. But courage comes after the action. So, when that inner critic chimes in, pause, acknowledge it, and then take one small, bold step despite it. Courage isn’t the absence of doubt. It’s action in the presence of it.

“It was a sign that I was pushing into something that mattered—something that was difficult, but worth doing.”

I didn’t get rid of my inner critic. I just stopped letting it drive. Even now, it still shows up before big decisions or at the start of new chapters, but I’ve learned to recognize its tone. It’s never curious. It’s never kind. It always speaks in absolutes: you’ll never, you can’t, you shouldn’t. When I hear that voice now, I take it as a clue, not a command. It’s a sign that I’m stretching into something that matters.

2. One minute, one hour, one month.

During an airshow in Columbia, I was flying my Thunderbird jet at 400 miles per hour, just a couple of thousand feet above a forest. Suddenly, I saw a flash of light, heard a loud thud, and felt the jet shake. I had just hit a bird. Later, I’d find out it was a vulture with a six-foot wingspan, but in that moment, all I knew was that this was serious. I didn’t know how bad the damage was. Was the engine okay? Would the aircraft keep flying? My adrenaline spiked, but I didn’t panic. I fell back on a mental checklist that we drilled from day one in training:

- Maintain aircraft control (don’t make it worse).

- Analyze the situation (what do I know?).

- Take proper action (what can I do about it?).

First, I focused on flying the jet, checking my instruments, and communicating with the rest of the team. Not fixing, but assessing, then acting. I still use that same process when things go sideways in life, but I translate it like this: What do I need to do in the next one minute, one hour, and one month?

- One minute: pause, breathe. Just let yourself feel it. Ground yourself in your body.

- One hour: analyze, gather facts. Get support.

- One month: adjust your habits, actions, and mindset.

Whether it’s a breakup, a layoff, or a deal falling through, you don’t need to solve everything all at once. When a bird hits your jet or life just hits you hard, start with the next minute because how you respond in small windows determines how you navigate the big ones. That bird strike could have gone very differently. If I had let panic set the tempo, I could have turned a bad moment into a catastrophic one, and I think we do that in life, too. We try to sprint through things that need a steady walk.

When something goes wrong, don’t just ask, What should I do? Ask what matters most in this moment? What can wait, and what can I shift long-term? That’s how you lead yourself through pressure—not perfectly, but with purpose.

3. Wiggle your toes.

Air refueling is when one airplane takes gas from another while flying alongside each other at over 300 miles per hour, thousands of feet in the air. It is a skill that requires practice and finesse, and it is stressful to learn. As a newbie pilot with little experience attempting this task, I was tense. My hand was going numb and I was gripping the stick like it owed me money, and every time I got close to the position where our airplanes would actually touch, I’d overcorrect, become unstable, and be told to back up and try again.

After one particularly bad flight, my instructor gave me this piece of advice: “Mace, when you get close, don’t forget to wiggle your toes.” It sounded silly considering we were trained combat pilots flying $30 million aircraft, but on the next flight, I gave it a try. As I felt the stress build, I consciously moved my toes inside my boots, and it worked. That tiny movement disrupted the tension in my body. It made me breathe, relax, and refocus.

“When pressure rises, your instinct might be to grip tighter, but sometimes the best move is to loosen your hold.”

Wiggling my toes became a ritual, and not just in the jet, but anytime. Stress made me want to control everything too tightly. When pressure rises, your instinct might be to grip tighter, but sometimes the best move is to loosen your hold. Try wiggling your toes. It’s a physical disruptor. It breaks the stress spiral. It buys you a moment to respond with intention instead of reacting under duress, and sometimes that’s all you need to regain control, not by force, but by presence.

4. Call signs are earned, not chosen.

In the fighter pilot world, we have nicknames that we refer to as call signs, and you do not get to pick yours. It’s given to you, usually after a mistake you made as a young pilot. Mine came during basic fighter maneuvering. I got so focused on the wrong thing that I accidentally broke the sound barrier—I was supersonic when I wasn’t supposed to be, and didn’t even realize it. I didn’t even understand what had happened until after we landed and watched the cockpit recordings during our debrief.

Not long after, I was officially named Mace (an acronym for “MACH at circle entry”). This wasn’t a compliment. It was a reminder of a rookie mistake, and I honestly felt a lot of shame around it. Then I thought about how every single pilot in my unit had a call sign, even the most respected, the best, the most experienced. I realized that when you’re doing something hard, no one gets by unscathed, and it wasn’t perfection that led to success, but persistence.

Our identities are often shaped by how we recover from missteps, not how we avoid them. That moment became part of my growth. I eventually owned it. I learned from it, and I flew smarter because of it. You might not get to control how every chapter of your story starts, but you do get to decide how it ends. I used to carry so much shame around that call sign, but then I realized it meant I was in the game. You don’t get a call sign if you’re sitting on the sidelines. You get one by showing up, getting it, and still coming back for more. All the people I looked up to had a moment they’d rather forget. Confidence doesn’t come from never falling. It comes from proving to yourself that you can rise after you do.

5. What’s your go/no-go criteria?

In aviation, we use the concept of go/no-go decisions. This is something you decide before the mission ever begins, not when things are falling apart. Before every flight, especially ones that push limits, you set your criteria. If the weather drops below a certain level, no go. If fuel hits this mark, go home. If the system isn’t functioning, abort the mission. Why? Because once you’re in the air, the variables increase, and so does the pressure. You’re emotionally invested, and that’s when people make poor decisions. They press forward toward an objective and into danger because they’re already in motion. A great example from mountaineering is summit fever, when a team pushes ahead because that summit is so close, even though they’ve already passed their turnaround time. Go/no-go keeps you honest and calm so that when chaos hits, you don’t have to figure it out. You just follow the plan.

“You’re emotionally invested, and that’s when people make poor decisions.”

I’ve used this concept in my personal life. Whether business, relationships, or big goals, I try to set my limits and values before investing time, money, and energy. What am I willing to compromise on? When will I walk away or shift course? This is where the sunk cost fallacy kicks in. We tell ourselves that we’ve already come this far and invested too much to quit now, but that logic traps us in bad decisions. The time, energy, or money you’ve already spent is gone. What matters is whether continuing is still aligned with your values, safety, and mission.

Go/no-go protects you from doubling down just to justify your investment. It gives you a way to honor your effort without letting it dictate your future so that when things deviate from the plan, you don’t have to scramble to find clarity. Bold doesn’t mean reckless, and quitting isn’t the same as failing. Draw those go/no go lines before you need them because decisions made in calm are what guides you in chaos.

Enjoy our full library of Book Bites—read by the authors!—in the Next Big Idea App: