Laurie Simmons is an award-winning photographer, filmmaker, and writer. Recently, she was honored at the sixth annual International Center of Photography (ICP) Spotlights benefit, which recognizes the achievements and contributions of women working in photography and film. At the event, Laurie was joined on-stage by actress, writer, and singer Molly Ringwald for a lively conversation about the creative process, whether motherhood influences art, and the aesthetics of loneliness.

This conversation has been edited and condensed. To view the full conversation, click the video below.

Molly: You once said you didn’t necessarily consider yourself a photographer, but more as an artist who used the camera. Why did you decide to use the camera instead of choosing a different medium?

Laurie: I came to New York in 1973, 1974, at a time when conceptual art, process art, and video were just bursting wide open. My very formal, rigorous art school education—print-making, painting and sculpture—didn’t seem relevant. Conceptual art was really about people picking up a camera because they had to document what they were doing. I thought, “A camera—maybe that’s an interesting tool.”

Also, I wasn’t aware of a lot of women photographers at the time, and I thought, “Maybe this path is a little clearer for me than painting or sculpture” which, as art history had been taught to me, most of the characters were male.

Like a number of other women artists at the time, I saw a clear path to something that we might be able to invent, or at least mold into our own.

Molly: How did you actually learn to take pictures? When you started, you weren’t working with digital as you do now, you had to work with a dark room. Did somebody actually teach you the technique?

Laurie: Kind of. I shared a loft with the photographer Jimmy De Sana, who died of AIDS in 1990. (I’m also the executor of his estate). We got a two-hundred-foot-long loft in Soho, for no money, and put a dividing wall in-between; I built a darkroom, he had a darkroom, and basically I just started trying to figure out what to do.

He taught me everything I knew, and when he wasn’t around, there was this thing called the Kodak Hotline. I called so many times that I started disguising my voice, putting on different accents because I thought, “This guy’s not going to answer any more of my questions.”

Between Jimmy De Sana’s instruction and what I learned from the Kodak man, I was really self-taught.

Molly: How long does it usually take you to take a photograph?

Laurie: I work in series, so when I get an idea, I set it up, and I shoot, and I shoot, and I shoot… and the series can go on for one month or two years. It’s hard to say. I’m sure a lot of artists would share this feeling with me, but I know when things are over. I know when they begin, and I know when they’re over.

Molly: Tell us a little bit about this series that we’re looking at right now.

Laurie: This is work that was made when I was having those really private days in the dark room with Jimmy De Sana, around ’75, ’76. It’s the first work that I ever actually exhibited, at Artist Space in New York in 1979, and it got reviewed in The Village Voice, which is still one of the most exciting things that’s ever happened to me.

The article was called, “Robert Frank and the Trap of Life,” and even though I was a baby booming feminist, I was floored when it referred to me as a feminist artist.

Molly: Did you consider yourself a feminist?

Laurie: Yes. I didn’t think I was making art about that, though. Nor did I want to because I felt that the generation before me had marginalized themselves by calling themselves feminist artists. Like a lot of women in my generation, I wanted to play with the big boys, I wanted to hang in museums, I wanted to do everything that was available.

Trending: Navy SEAL Secrets for High Performance Under Pressure

Molly: When you look back on the art now, do you view it as feminist art? You say you were surprised at the time, but when you look at it … to me, it does say feminist. I say that in a good way, because I think feminist is not a bad word.

Laurie: I don’t think feminist is a bad word, and it’s starting to become clear to me that a number of young women do think it’s a bad word. I’d like to know why.

I think that I was making work about memory. Those pictures were not a critique about a housewife being enmeshed in her own possession, or being trapped in her own home.

Molly: This image from the Cowboy series—you once said that you took these figures from your husband, right?

Laurie: Yes, they were his toys when he was little, and he called them the big figures. In my work I’ve gone back and forth between shooting surrogates—dolls, mannequins—and then trying to shoot real people, and also trying to shoot men, to balance it out so I’m not just a woman who takes pictures of women, even though I feel like my subject is, and always has been, a woman in interior space. Even my films are that.

This is a way to deal with men, because these are the guys that would’ve been on the TV in the 1950s, all those cowboy shows like Gunsmoke. And the Marlboro ads had a strong effect on me, in terms of wanting to command that imagery, to take and have it be my own.

Molly: Well, men and cowboys… I think they’ve been idealized the way that women have been idealized in the domestic spirit, right?

Laurie: Absolutely. I feel like the housewife and the cowboy make a great couple in some worlds.

In 1983, I created color-coordinated interiors when I got this set of Japanese dolls. They’re called Teenettes: it was a Japanese toy maker’s idea of what an American girl looked like.

I would color-coordinate them with rooms because the most striking feature of the home I grew up in was that everything was color-coordinated in the most amazing way. I am programmed to see color-coordination. I can tell you that your lipstick and your hat match.

Molly: They do.

Laurie: I’m programmed to make those connections because of how rigorous the steps were that everybody took to make sure that the world matched. And I love shooting black and white, but I’m really most conversant in color. As a child, I could identify people’s lipsticks. If you had to have a pair of shoes dyed to match a dress, I didn’t have to use the color chart. These were things that I just intrinsically understood.

Molly: Can you give a feeling of the size of these dolls?

Laurie: The dolls are about four inches high, and the prints are five feet, six feet, they go up to being ten feet by five feet. So these were really large, but the dolls were really small.

In this series, I took the dolls out into the world and moved them around the most cliched monuments and tourist spots like Stonehenge and the Statue of Liberty and the Eiffel Tower. The great monuments are built by men, and they’re very phallic, so having these little dolls travel from place to place and then blowing them up to a much larger scale was appealing to me.

Molly: By this point, you were married. Do you feel like getting married and having children affected your art in any way?

Laurie: I’m really glad you asked that question, because if someone asked me that twenty years ago, I would refuse to answer because I felt like all artists should be on a level playing field, men and women, gay and straight, and people were not asking them that question.

Now I think it’s really important to answer the question because there are so many young women artists who feel like it’s not appropriate to have children, and a number of them have actually come to me and asked me my thoughts about it, about the idea of being an artist and having a child.

Of all of the things that everybody says about Hillary Clinton, I haven’t heard anybody criticize her for being a mother. Or Ruth Bader Ginsburg, or Meryl Streep, or Margaret Thatcher. Why the conversation exists in the art world is baffling to me.

One of the ways that having children changed my work was that it made the structure of going into the studio much more regimented: “I have to get in there on these days, and I can’t work all night the same way that I used to.”

Molly: Going back to that idea that feminist can be a loaded word, why would being a mother, and it influencing your art, ever be considered a bad thing?

Laurie: Well, I don’t know if being a mother, per se, influenced my work, although it’s interesting that in my 1987 ventriloquism series, where I made three trips to a ventriloquist museum down south, and photographed hundreds of dummies against a background—moving and carrying them around—it occurred to me that I was then going back home and picking up a child who weighed relatively the same.

At the time, I was really coming into my full blown adult political awareness. What I was thinking about is: who’s actually speaking? Who’s really speaking when we read the newspaper, when we listen to a politician, or the newscasters? Where is the information coming from? It was the moment when I became mature enough to understand how to disseminate all the information that was coming at me. That’s what I was saying these pictures were about—the fact that they mirrored carrying small children around, or a child, was something that I can see in hindsight. Often times I think the artist is the last one to know what the connections really are.

Molly: I love your series [about objects on legs] that you revisited recently for New York magazine. What was the inspiration?

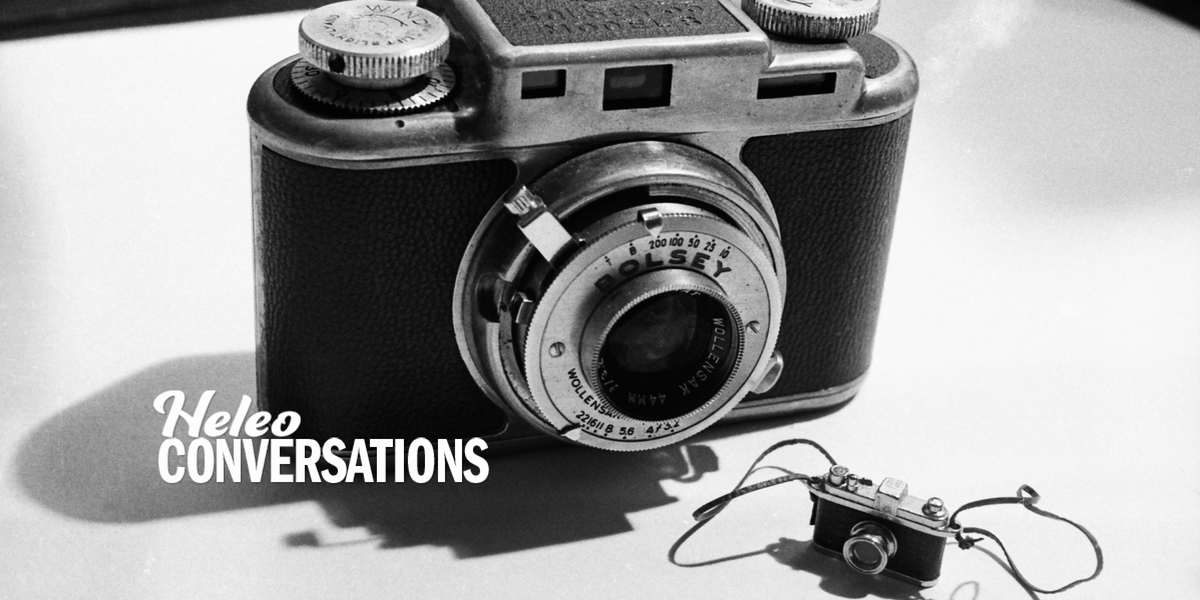

Laurie: This was my friend Jimmy De Sana in the camera. The camera was from the movie, The Whiz, which we were able to borrow from the Museum of the Moving Image.

Trending: How to Make Menopause the Best Time of Your Life

It was 1987 and we both knew that he was dying of AIDs, though it wasn’t something we talked about a lot. This was an homage to him in the sense that he had taught me everything I knew, and he loved posing for it. It makes me so happy that people associate this picture, probably first and foremost with my work, because it’s so much about him and my relationship with him.

I think that the reason I thought about doing these objects on legs was that the ventriloquist series had been so much about the brain, and I wanted to think about brawn, and the way that we as women have to hold up the possessions, that we become subsumed by them, we become defined by them.

In a sense, this was more of a classic feminist statement that the early doll house pictures.

Molly: Right, that feeling of carrying around a lot.

Laurie: Well, I mean, who hasn’t felt like that?

Molly: I feel like that every day. For some reason, I carry a handbag, and a bigger bag, and then a satchel. Every day I find myself carrying so much stuff, and I think, “It is purely psychological.” It’s like I need to manifest in what I’m actually carrying, and this series reminds me of that.

Laurie: You need to take your life with you. I think that a lot of people feel that.

Molly: In this image, you seem to be getting across the feeling of time.

Laurie: Yes, I was starting to think about aging, and all of the ways that I could portray that without hitting you over the head with it.

Molly: I’ve always thought that to be an artist would make you feel not as susceptible to the idea of aging, but is that just a complete fallacy?

Laurie: Yes. I think it would be impossible to be a woman in our culture and not to think about issues around aging. It doesn’t mean that everyone hates the age that they are and wants to be young, but it’s there for us to see, every single day. We’re manic about youth in the United States.

You’re in an interesting position. You’re playing Aurora in Terms of Endearment off Broadway, which was the part played by Shirley MacLaine, and it’s hard to realize because in the ’80s, women were represented so differently, so the idea that you’re the same age now that Shirley MacLaine was when she played Aurora is amazing to me.

Molly: Almost unfathomable. When I got the call and they said Terms of Endearment, the first thing I thought of course was the Debra Winger part. When I realized it was the Shirley MacLaine role, I had to take a step back. I said, “I need the weekend to think about it.” Ultimately I decided to do it, mostly because there are very few parts for women of any age, and particularly a part that was this good. But it is true that 48 right now in 2016 is completely different than it was in 1983.

I don’t think it’s only women who feel the emotional impact of age. I think it’s something men feel a great deal, too. Even though they do get a pass physically that women don’t get, I still feel like there is that impact on men as well.

Laurie: I agree, and as an artist, I think about all of the work that I want to do, and I start counting, “Do I have enough years left…”

Molly: To say everything you want to say in your art?

Laurie: I think that everyone is battling the idea of a limited amount of time. That’s universal.

The dummies inspired the first movie that I made, The Music of Regret, a musical in three acts. It was a way for me to say goodbye to all of the series I’d done up until 2006.

Molly: You wrote the music?

Laurie: I wrote the lyrics. Michael Rohatyn wrote the melodies, which are beautiful. I cast the dummy as an image of me, and then I cast Meryl Streep to play the dummy.

Trending: Microsoft, Google, and Beyond: What Business at the Cutting-Edge of AI Looks Like

Molly: How did you end up with Meryl Streep in your project?

Laurie: I’ve known her for years. Her husband is a very well known sculptor, and I knew that Meryl liked to sing—this was before Mamma Mia. I hoped that if I played her the songs that she would say yes, and she completely fell in love with the songs.

She was going to be able to sing with Adam Guettel, who wrote Light in the Piazza, who was also the grandson of Richard Rogers, so there were lots of things in my favor, things that I thought as an actor that she would want to do.

Molly: Was it daunting that your first experience directing a film was directing Meryl Streep?

Laurie: Well, you don’t direct Meryl Streep. You just stand there and she does her thing. Perfectly. That was really not a directing experience.

Molly: What was behind your decision to work with film since filmmaking is not in your roots?

Laurie: In my shoots, I kept upping the ante—I needed more and more moving parts when I was shooting, and I can’t think of another situation, except if you’re a general of a large army, where there are so many moving parts as there are in making a film. There’s the writing of the script, the editing of the script, trying to raise money to make the movie, and trying to actually make the movie, then the editing, the sound edit, the visual … I mean, it’s so completely engaging and gripping.

Molly: And everything needs to work together in harmony.

Laurie: Everything needs to work together, yes.

Molly: Why do you sometimes shoot without figures?

Laurie: It feels right to me, sometimes, to shoot without figures or dolls—periodically, I just make really empty spaces. And if I’m exhibiting the work and standing in the gallery, it’s amazing to see people’s eyes glaze over like, “Where’s the doll? I’m out of here.” Sometimes the places I want to be don’t have figures in them, and I feel like that’s where I am when I look through the viewfinder.

Molly: Sort of like the difference between being an extrovert and an introvert? These images to me seem more introverted. More peaceful, in a way.

Laurie: Exactly. Whatever the camera factors out, or whatever I lose in my peripheral vision, makes me feel that I’m psychically standing in that place, which reminds me of the feelings that I had when I would sit on my mother’s lap and she would read a book.

Molly: I feel like it evokes the same thing in the viewer. It’s like reading a book that doesn’t… I tend to gravitate towards authors that don’t describe the person physically in detail, so I can invent my own image, and these images do that for me, where you sort of imagine the rest.

These final images are some of your most recent work?

Laurie: Yes, they’re called “How We See” and the fashion models’ eyes are closed.

Molly: They’re so beautiful—and so creepy.

Laurie: They really are. They’re striking, you can’t stop looking at them. It’s that classic “there’s something wrong with this picture” situation. And there is—their eyes are closed.

It speaks to so many of the things that I’m thinking about: identity, identity politics, and the idea that the person that we meet on the internet, the person that we project on the internet, may not be the person that we think it is at all. I’m interested in false identity, and the way we’re able to mask our identity.