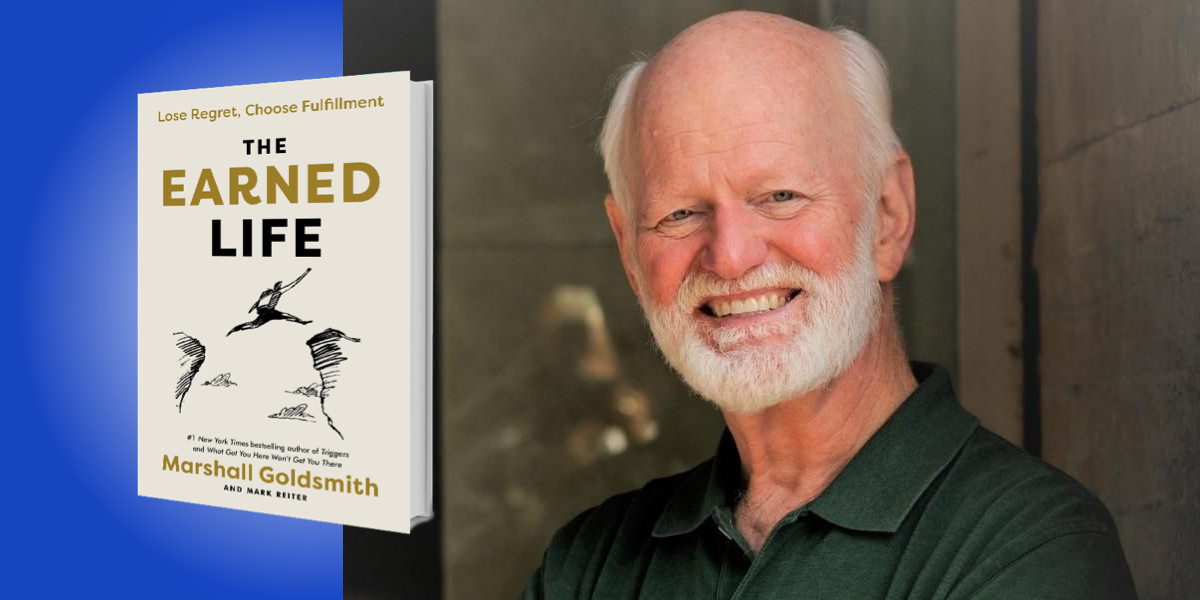

Marshall Goldsmith is an executive educator and coach who has been ranked the number one leadership thinker in the world (twice) by Thinkers50. Mark Reiter is his longtime collaborator.

Below, Marshall shares 5 key insights from their new book, The Earned Life: Lose Regret, Choose Fulfillment. Listen to the audio version—read by Marshall himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Align your aspirations, ambitions, and actions.

What do you need to have a great life? Well, assuming that you have your health, some good relationships, and at least a middle-class income, three things matter.

First, we need an aspiration. You need an answer to the great question, “Why am I working so hard? Why am I doing this?” The aspiration doesn’t have a particular target or a finish line—it’s a broader goal explaining why we’re doing something. Second is our ambitions, what we’re trying to achieve. There is a finish line, a target, or a deadline. And the final element is our actions, our day-to-day activities.

Most human beings tend to get lost in the action phase. If you look at the history of our species, our ancestors didn’t have money. They lived on a day-to-day basis, and didn’t have time for lofty ambitions. They pretty much did what was in front of them. And today, you still see a lot of people stuck in this action or immediate phase—people who are video game addicts, or wasting large amounts of time on social media. On the other hand, some people get stuck in their aspirations. They’re great about looking at what’s important, the big picture of life—but they don’t actually do anything. They don’t achieve a whole lot.

Most of the people I coach get stuck in the ambition phase, and get lost in the excessive desire for achievement. You never, ever want to base your value as a human being on what you achieve, and that’s for two reasons. One is that what you achieve is not under your total control; there are many variables impacting success that you don’t control. And two, what happens after you achieve something? How much long-term satisfaction does that actually bring? Usually not much—and we have to achieve more and more and more. I’m a philosophical Buddhist, and the Buddhist term for this is a “hungry ghost”: I’m always eating, but I’m never full.

2. Eat the marshmallow.

There’s some fascinating research on marshmallows done by Walter Mischel at Stanford. In this famous research, he gave each kid a marshmallow. He said, “If you eat one, you get one. But if you wait, you get two.” They ran a longitudinal study, and the kids that ate one marshmallow never amounted to much in life. The point of the research was that delayed gratification is good, a message we are constantly bombarded with in the West.

“If all we do is delay gratification, what do we get a lot of? Delay. What do we not get a lot of? Gratification.”

But here’s the problem. They didn’t take the kid who ate two marshmallows and say, “Hey, kid, wait a little bit more, and you get three. Wait a little bit more, and you get four, five, ten, a thousand!” Where does the story end? It ends with an old man in a room waiting to die, surrounded by millions of uneaten marshmallows.

There’s a story about Jack Welch, the former CEO of GE. He almost died, and he had triple bypass surgery. A friend of mine asked him, “Jack, what did you learn about life when you almost died?” And he said, “Why am I drinking the cheap wine?” Jack Welch had an incredible wine collection, but he wasn’t drinking it—he was waiting for it to appreciate in value. He finally realized, “I’m Jack Welch! I’m already rich, so what am I doing?”

If all we do is delay gratification, what do we get a lot of? Delay. What do we not get a lot of? Gratification. The point is: sometimes, you’ve got to eat the marshmallow.

3. The “new me” paradigm.

This is based on the Buddhist philosophy of impermanence. As we journey through life, we are constantly reinventing and recreating ourselves. And the great Western myth is that we’re going to get to a place that lasts forever. This is the “I’ll be happy when” myth—“I’ll be happy when I get the money, status, BMW, condominium.” Well, there is no when. There’s a certain kind of book that ends, “…and they lived happily ever after.” Unfortunately, this book is called a fairytale. It’s not the real world.

I spent the COVID lockdown with a group of amazing people who inspired me to write this book. And one of them was named Safi Bahcall. He has a Ph.D. in physics from Stanford, he started four companies, he wrote a number-one bestselling book called Loonshots—he’s an amazing man. But Safi had always believed, “If I achieve enough, I will be happy.” But finally he realized, as he put it, that “happiness is not a dependent variable based on achievement.” He realized that you can achieve a lot and be happy, or you can achieve a lot and be miserable. You can achieve absolutely nothing and be happy, or you can achieve absolutely nothing and be miserable.

“You can achieve a lot and be happy, or you can achieve a lot and be miserable.”

4. Credibility must be earned twice.

We all want to build credibility, to be seen as trustworthy people. In order to do this, two things have to happen. One, we have to be competent—we have to do great work. And two, we have to be recognized for doing this great work. These are two completely different variables.

Some people have this ridiculous idea that good work will speak for itself. But your good work will not speak for itself. Now, I’ve been blessed to sell about 3 million books. How many books do you have to sell on Amazon in a year to be in the top half of all the books sold out of the 33 million? I think the answer is two. 16 million books sold almost nothing! Now, I’m not arrogant enough to believe my books are actually better than 16 million other books. I’m sure many of them are wonderful books—but no one read them.

If you do a Google search for seeking or needing approval, it’s considered a psychological dysfunction. That is insane! We all need approval. After all, you’ve been taking test after test in school, and you had to prove you’re smart—you had to gain approval. But while gaining approval is important, the question is, “When do I strive for approval? When do I try to prove myself, and when do I not?”

In the book, we talk about something called the “credibility matrix.” The credibility matrix looks at two dimensions: one, making a positive difference in the world (which I learned from Peter Drucker; that’s what we’re here for in life) and two, promoting myself, trying to gain approval. One thing the matrix illuminates is called “overselling.” People who oversell promote themselves too much, try to win when they don’t need to win, try to prove how smart and great they are—there are dangers in overselling ourselves.

And then there’s “underselling.” This is a bigger problem: people who really think they’re great, but are hesitant or embarrassed to promote themselves. To the undersellers, I ask three questions: one, would the world be worse off or better off if you became more powerful and influential? (They almost always say better off.) Two, do you feel uncomfortable promoting yourself? (They typically say yes.) And three, what’s more important: making the world a better place, or being comfortable? Well, get over yourself! If you want to make the world a better place, you’ve got to go out there and market! If good work really spoke for itself, no company would need a marketing function.

“If good work really spoke for itself, no company would need a marketing function.”

So, the idea is that we want to build credibility by promoting ourselves when we should, when it’s going to make a positive difference, and not promoting ourselves when we shouldn’t.

5. The LPR.

The Life Plan Review (LPR) is what I did during COVID with a group of great people, and it builds on something called the “daily question process.” I talk about the importance of making a list of what’s important in your life, and evaluating how you did every day.

I talk about some important questions like, “Did I do my best to set clear goals today? Did I do my best to make progress toward achieving these goals? Did I do my best to find meaning? Did I do my best to be happy? Did I do my best to build positive relationships? Did I do my best to be fully engaged?”

As a group, we met week after week during COVID to go over these basic questions of life, and people loved it. Why? Because you get accountability, and you don’t have judgment—it was a support group. And there’s an old saying: “It’s lonely at the top.” This group contained some of the most influential people in the world, and they loved the opportunity to honestly share what was going on in their lives. They shared what was working and what wasn’t, to get ideas on how they could improve.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Marshall Goldsmith, download the Next Big Idea App today: