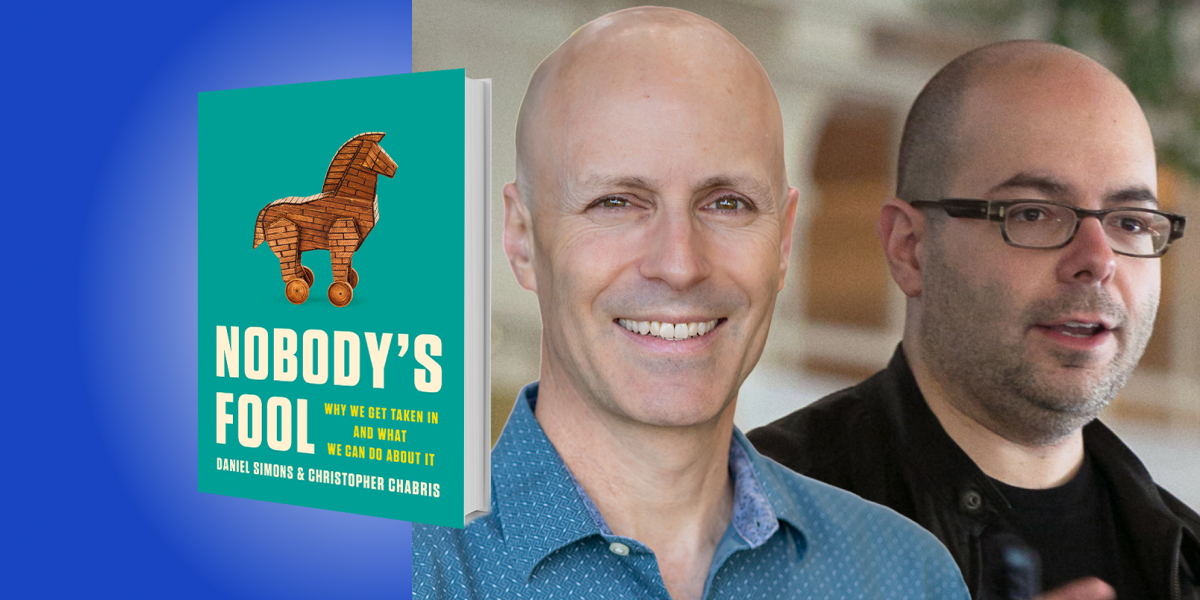

Daniel Simons is a Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Illinois where he also has appointments in the Gies College of Business and the Sandage Department of Advertising. Simons received his B.A. from Carleton College and his Ph.D. from Cornell University.

Christopher Chabris is a Professor at Geisinger, a healthcare system in Pennsylvania, where he co-directs the Behavioral Insights Team. He previously taught at Union College and Harvard University, and he is a Fellow of the Association for Psychological Science.

In addition to a number of academic honors and awards, Simons and Chabris jointly received the 2004 Ig Nobel Prize in Psychology—an award for research that first makes you laugh and then makes you think—for showing that it’s possible to hide a “gorilla” in plain sight.

Below, Daniel and Christopher share 5 key insights from their new book, Nobody’s Fool: Why We Get Taken In and What We Can Do About It. Listen to the audio version—read by Daniel—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. You can fool all of the people, some of the time.

In March 2022, a month into the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the international sanctions that followed, I got an email with the enticing subject line “Business Matter.” In poorly punctuated English, someone calling himself Mr. Bahren Shani offered to invest up to €200 million on behalf of wealthy Russians, as long as I could propose a “convincing business project.” Had I shown interest, Mr. Shani and his friends no doubt would have asked me to help pay some minor expenses first so that they could fund my project.

Advance-fee scams, like this one and the ever-present email from a Nigerian prince trying to recover his fortune, are deliberately incredible: both in that they promise absurd riches and in the sense of being not credible. Why should we believe that someone who emails us out of the blue and writes in broken English is likely to have access to vast fortunes? Why do they think I’m the right person to help them out? Why don’t these scammers use Grammarly or chatGPT to create more professional-sounding pitches?

Because the absurd email contents and broken English are a feature, not a bug. Scams are most profitable when they target only those who are likely to believe that the pitches are genuine. The obviously scam nature of these emails filters out skeptics, leaving just the recipients who are most likely to be victimized. The scammers don’t want to waste time interacting with skeptics who are unlikely to send money—that’s costly to them. But blasting out millions of emails to find the tiny percentage of people who are most likely to provide their bank information is cheap and effortless. It’s the same reason why pitches to extend your car’s warranty or to threaten IRS sanctions for unpaid taxes start with a robocall voicemail: anyone who calls back has self-identified as a target for the scam.

We might not be the sort of people who would fall for obvious scams like these, but the ability to spot obvious scams can give us a false sense of security. It’s dangerous, and wrong, to think that only the gullible, uneducated, or hopelessly naive get conned. Many of the victims of cons and scams were high achievers at the top of their profession. The victims of Bernie Madoff were mostly well educated and wealthy. The duped board members of Theranos were former U.S. cabinet members and retired generals. Scientific experts regularly fail to spot fake findings; in reality, any of us can be fooled, as long as we are the target.

2. Truth bias turns seeing into believing.

The Saturday Night Live characters Hans and Franz famously said, “Hear us now and believe us later.” The irony of their catchphrase is that we usually don’t wait until later to believe. Instead, we hear now, believe right away, and only occasionally check later. We tend to assume that what we see and hear is true, unless we get clear evidence otherwise. Many philosophers and psychologists argue that this “truth bias” is an essential feature of our cognitive architecture. Without a shared assumption that people generally speak the truth, we’d be unable to live together in communities, coordinate our actions, or even hold simple conversations.

However, “truth bias” is a necessary precondition for almost any act of deception. For example, in the “Fake President” fraud, made famous by the audacious French-Israeli fraudster Gilbert Chikli, a middle manager receives a call from someone claiming to be their own company’s president or CEO. The caller convinces the manager that they are uniquely positioned to help address a problem the company is having, such as making a purchase quickly, or closing a secret deal without too many people knowing about it. The caller asks the manager to transfer company funds and the payment actually winds up in the scammer’s account. The entire trick hinges on the manager’s willingness to believe that they are talking to the company head and that they are the only one who can help. If they don’t accept that the caller is who they say they are, they won’t fall for it.

“No legitimate organization or company will ever demand that you make payments using a prepaid card; that’s always a scam.”

If we start with a truth bias, a fast-talking scammer has a chance of ensnaring us before we think to check. The same principle applies in the “Call Center Scam”—the caller persuades a mark that they need to purchase cash cards and read off the numbers in order to avoid criminal charges. If the caller knows enough about their mark that they sound informed, people don’t tend to question as much as they should.

No legitimate organization or company will ever demand that you make payments using a prepaid card; that’s always a scam. Often scammers just lie directly about what they’re doing because they know few people will check. The crypto company FTX claimed that the money each person invested would be isolated and not used as part of other investments. However, it appears that they did exactly the opposite of what they promised. Scientists tend to trust that their colleagues are reporting what they did honestly and openly, but science fraudsters rely on that trust to pass off phony results and papers.

Outside the legal system, we rarely ask other people to affirm that they are telling the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth; in most contexts, that would be considered antisocial. However, asking ourselves whether a key piece of information is unquestionably true, or whether we should withhold judgment until we can verify it, can save us from the consequences of acting on a falsehood. Making a deliberate choice to remain uncertain and check more helps restrain our truth bias.

3. Precision does not imply credibility.

We all know that if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is. However, what’s fishy to one person is just plausible enough for another. Those looking to deceive us know how to make promises sound plausible by using the sorts of information we find especially appealing. For example, when they provide precise details, we’re less likely to be suspicious, and most of the time, that’s reasonable. All else equal, given a choice between a vague or precise statement, we would favor the precise one because precision often signals deep understanding. Knowing that it might rain sometime in the next day or two is less useful than knowing whether it will rain on your picnic scheduled for 5 pm. It shows a greater understanding of weather patterns to be able to make that accurate, precise forecast.

When a marketer says their brand of soap kills 99.9 percent of all bacteria or a business guru claims that 13.5 percent of customers are “early adopters” of new technologies, we assume those numbers have meaning and we rarely stop to question where they came from. Their precision gives their claim a patina of rigor and understanding, hijacking the appeal of precision to hook us. Most of the time, it doesn’t matter whether soap kills 99.9 percent or 99.8 percent or even just most bacteria. It doesn’t matter whether the actual percentage of early adopters is 13.5 percent or 10 percent or roughly one in six. If we take the precision and concreteness of the claim as a sign of true understanding, we’re opening ourselves to being deceived.

“The next time you see an exact number attached to a claim, consider that the precision might be intended to get you to lower your guard.”

Some marketers seem to care more about making their statements sound precise than keeping them straight. We recently reviewed a company’s website that promised to 3x your performance with its proprietary training program. However, later on the same page it promised to 6x your productivity, and elsewhere claimed to 5x it. Nowhere did the company promise simply to help you increase your productivity with their brief training. Meaningfully increasing your productivity with one simple trick might sound too good to be believed, but when we see a specific number associated with the increase, we tend to assume that their claims were evidence-based; we are more trusting. That might be why myths like the idea that we use only 10 percent of our brain, or that 90 percent of communication is non-verbal tend to stick; they attach a precise number to something that can’t easily be verified. The next time you see an exact number attached to a claim, consider that the precision might be intended to get you to lower your guard. A good way to check if you’re being misled is to ask whether you’d be just as persuaded if they’d used a different number or no number at all.

4. Surface your commitments.

In almost all cases of fraud deception and misinformation, victims could have stopped themselves before it was too late, had they surfaced their commitments. A commitment is a key assumption that, if incorrect, leaves us open to disaster. If unquestioned, a commitment leaves us unaware of our vulnerability. Many victims of Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme found it inconceivable that Madoff would ever screw them; they were fully committed to his trustworthiness.

In the early 2000s, we were each separately contacted by a fellow cognitive scientist who wanted to collaborate with us on research. He was polite, he dropped the names of respected scientists we knew, and he had some interesting ideas. For various reasons, the collaborations never got rolling, and it’s very fortunate for us that they didn’t. He turned out to have been involved in dozens of legal cases because of his long-running side hustle as a fraudster. He pretended to have credentials he didn’t and bilked people out of a few thousand dollars here and there. We never thought to check his background, and had we engaged with him, we could have become two of his victims. Many scammers, like this one, have committed fraud before, but we rarely investigate the people we’re dealing with. Even when the stakes are high, we just assume they are legitimate, especially if they sound like they are.

In some cases, fraudsters even have criminal records that could be found with a quick search. Recently the FBI raided an Orlando art museum and seized its collection of paintings attributed to Jean-Michel Basquiat. Most experts believe the paintings were fakes. Had the museum done the due diligence of checking out the backgrounds of the three men who had “discovered” the previously unknown paintings and provided them to the museum, they might have reconsidered the exhibition. Collectively, the three men had seven prior convictions for crimes, including drug trafficking, campaign finance violations, securities fraud, and consumer fraud.

Whenever we’re dealing with high-stakes decisions, we should carefully inventory and scrutinize all the assumptions we’ve made. Those are the times when a scammer will go to great lengths to set up a big score. Remember that someone who is entirely trustworthy and credible will come across that way when you talk to them, but so will a con artist.

5. Outsource your vigilance.

Have you ever wondered why some shops offer you money or a free meal if the cashier doesn’t give you a receipt? Do they really want you to have a record of your Big Mac purchase? No. It’s a fraud prevention measure, and a good one at that. In 2022, a Jimmy John’s manager in Missouri was fired for stealing more than $100,000. Whenever a customer paid in cash, he gave them their food and then simply canceled the transaction and pocketed the money. Generating a receipt prevents that sort of scam by ensuring that every sale is registered and incentivizing customers to make sure there is a receipt helps the store prevent fraud. On top of this, it doesn’t require the store owners to distrust their employees individually.

“It’s much harder for someone to fudge numbers if they know someone else will be checking to see if they get the same results.”

The rock band Van Halen famously implemented their own automatic trustworthiness check. As part of their concert rider, they asked that the venue provide a bowl of M&Ms, but with no brown ones. If they checked the bowl and found any brown M&Ms, they knew that the venue wasn’t paying close enough attention. They figured that if they could screw up a bowl of M&Ms, they could also make mistakes with the extensive rigging and pyrotechnics in their show, and the band members did care about those. Researchers like us have our own variants of the M&M test; we include questions in our studies and surveys that are designed to check whether our participants are following instructions. If they get those questions wrong, we know not to trust their other answers.

Researchers can also use the trick of requiring receipts to prevent scientific fraud. For example, we can make sure at least two people involved in any project analyze the data independently. It’s much harder for someone to fudge numbers if they know someone else will be checking to see if they get the same results. Having such a process as standard practice means that we don’t constantly have to second guess or distrust our colleagues. Doing this perhaps could have prevented recent cases of scientific fraud in which prominent researchers fabricated data right under the noses of their equally famous co-authors.

These sorts of preemptive fraud detection measures can help, but to implement them, we first have to anticipate what might go wrong or how someone might rip us off. Doing that requires us to spot gaps in our own thinking and procedures, which can be as hard as spotting our own typos. This is why the military uses red teams whose sole job is to find weaknesses in a plan of engagement, and it’s why software companies pay bounties when outsiders find bugs. Whenever you might be at risk of a bad decision, and whenever adopting a scammer’s perspective is challenging, it can pay to have someone else do it for you.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Daniel Simons, download the Next Big Idea App today: