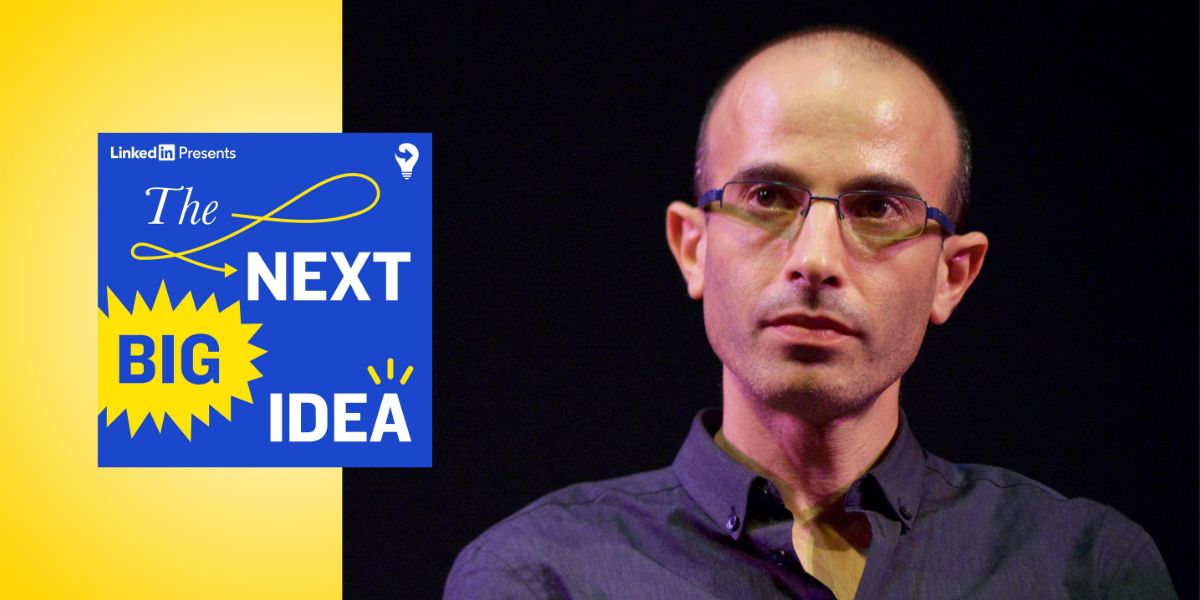

Yuval Noah Harari is a historian and philosopher whose books — Sapiens, Homo Deus, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, and most recently Unstoppable Us: How Humans Took Over the World — have sold more than 40 million copies. He joins our host, Rufus Griscom, for a wide-ranging conversation about storytelling, life in the Stone Age, the future of democracy, and the threat of AI.

If you want to listen to this and other episodes ad-free, and enjoy hundreds of audio summaries of the best nonfiction books, written and read by the authors themselves, download the Next Big Idea app.

Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | The Next Big Idea app

Topics

- Storytelling is our superpower

- Understanding the ancient past changes our contemporary worldview

- Our innate longing to live like hunter-gatherers

- Harari’s critique of The Dawn of Everything

- What the Constitution’s framers got right

- The biggest advantage of liberalism

- Why Democrats and Republicans are more ideologically aligned than you may think

- Democracy is built on information technology — and now that technology is undermining the democratic system

- AI is the first technology that can take power away from us

- If we are not careful, AI and bioengineering will be used to create the worst totalitarian regimes in history

- Be skeptical of technological determinism

Transcript

Rufus Griscom: Yuval Noah Harari, welcome to The Next Big Idea podcast.

Yuval Noah Harari: Thank you. It’s good to be here.

Rufus Griscom: Yuval, you wrote a book, it was first published, I think, in Israel more than 10 years ago now, called Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, which tells the story of our species in an unusually direct and provocative style. And it has been colossally popular to a degree that has really excited me personally. I was, I think, among the early readers in the US. And I was astonished to see so many people so interested in a scientific explanation of our species. I was also interested to see that it irritated a few of your academic friends.

I think one anthropologist said the book is fundamentally unserious and undeserving of the wide acclaim it has been receiving. So I’m curious, why do you think Sapiens had and continues to have such a massive global impact, and why the resistance from some corners of academia?

Yuval Noah Harari: The basic reason is that we now live in a global world. So to understand our lives, we need to understand the totality of human history, the history of our species and of our planet, and not just the history of one people or one country or one culture. And that’s the attraction. And especially, in most countries, at least in my country, in Israel, they don’t teach the history of humanity, they only teach the history basically of Israel and the Jewish people.

Sometimes you hear about, I don’t know, the French or the Romans, but only in the context of what they did to us. So you can finish school and never get a big picture of the history of the world, and we need it. And the reason that at least my approach has been criticized by some academics is because to write the history of the entire world in 400 pages or 500 pages, you need to skip over many things. You need to simplify many things. That’s the deal. You can’t write the history of humanity in 400 pages and do it like you write an academic paper for a professional journal.

So some people criticize this approach. But I also got a lot of very positive feedback. And in the end, I don’t see these kinds of books as replacing the kind of rigorous, in-depth academic research that I did as a researcher and as both of my colleagues still do today. We need this. Without these articles on a single archeological side covering just a single year, it would be impossible to write a scientific history of humankind.

What we really need is cooperation. I see my role is mainly a bridge, that I bridge the gap between the academic community and the general public. So I read as much as I can the in-depth studies of anthropologists and archeologists and geneticists and historians, and I try to translate them into a very broad and accessible narrative that would reach a wide public.

Rufus Griscom: And what’s so interesting is this simple direct approach that you took that I think was born out of a process of preparing for this world history class that you were teaching your students. And there’s this wonderful story that you preferred not to engage in a lot of public speaking. So you preferred to write the scripts and you had limited space and time. So you had this incredibly concise, direct, declarative approach that, as you say, by necessity, had to cut out some of the complexity of the controversies in various fields and endless citations.

And in the process of doing that, it ended up harnessing the power of the thrust of the story of our species with our species as the protagonist, and it turned out that that just resonated right in this way that I think surprised you, didn’t it, as much as it surprised many others?

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah. I thought it would reach a limited audience of maybe students at university who needs this kind of broad introduction to history. But yeah, it turned out that many people out there want to have an understanding of our history. And in a way, it’s obvious because I can’t really understand myself without understanding the history of our species. Now, if you think about a more narrow approach to history, so the old-fashioned history of kings and battles and dates, so most people, they don’t see how it is connected to their life.

I mean, okay, if some king won some battle a thousand years ago, why should I care about it? What does it have to do with my life today? And I think, in a curious way, when you broaden the scope, it becomes obvious why it’s relevant to your life today. That almost everything we think and we do and we feel comes from history. Even if you’re a kid and you wake up in the middle of the night afraid there is a monster under the bed, this is actually a historical memory from hundreds of thousands of years ago when our species lived in the African Savannah and there were monsters that came to its kids at night, a lion would come or some cheetah would come. And if you wake up in fear and call your mom, then you have a chance of surviving.

And these kinds of insights of how the past still shapes the present, this is what makes history relevant. And it’s not just our fears, it’s also our desires, our passions. Lots of people are struggling today with food issues. And again, especially kids but also adults, we tend to eat a lot of sugary and fatty food, which we are told it’s not good for you. And you have this question, “If it’s not good for me, why does it taste so good? Why do I want to eat it? Is there something wrong with my body? Does my body want something which is not good for it?”

And when you look at it from the perspective of the present, it really makes no sense. But when you look at it from the broad perspective of human history, it suddenly makes sense. Because again, this is a historical memory basically that when we lived in the wild, there wasn’t a lot of food, certainly not sweet food. The only sweet things were either honey or ripened fruits. And if you live in the Savannah and you come across a tree full of ripened figs and you eat just two or three of them and go away and say, “Okay, I’ll come back tomorrow, eat some more.” When you come back tomorrow, there is nothing left because the baboons came at night and ate everything.

So we have this program built inside us that if you encounter a sweet food, eat as much of it as quickly as possible. And it made perfect sense in the Stone Age. It doesn’t make much sense today for many people, but our body doesn’t know that it lives in the modern world with refrigerators and supermarkets and all that. Our body is still programmed basically for the Stone Age. So understanding how our ancestors lived in the Stone Age is still extremely relevant to our life today. And finally, to give one other example of the relevance of history is that, very often in life, we encounter laws and rules, you can do this, you can’t do that. And a very big question about almost any of these rules is where do they come from? Are they natural laws or is it something invented by some human being in the past?

In many countries, until the very recent times, the rules said that only boys get education. Only boys can go to school and later to university and become priests or rabbis or professors. And when people asked about this law, they were told either that this is a law of nature, it’s nature that made men superior to women, or it’s a law of God, God’s decree that this is how the world would function. And the way that history helps us is when we study the history of education and the history of gender and of religion, we realize this law doesn’t come from biology and this law didn’t come from God. It came from some humans who invented the story 2000 years ago, a 1000 years ago, and it’s just a story invented by humans. It’s not true.

And when you realize that as many people realized over the last century, you change the rules. You say, yes, girls can go to school, women can be politicians and professors and journalists and so forth. So knowing what comes from history and what comes from biology, it’s one of the most important and controversial issues. And again, this is not some king who won a battle a 1000 years ago, this is about how we live our lives today.

Rufus Griscom: Your latest book, Yuval, Unstoppable Us: How Humans Took Over the World is for children, kids eight to 12. I have a 12 year old son with whom I’ve been reading the book. I was very happy that you included the business about the impulse to eat all the chocolate cake in the refrigerator because he has a sweet tooth. Really, we read that section twice. But I agree that it’s empowering for kids of all ages and adults and all of us to understand that humans are the source of everything and we can change it. And one of the themes of course is that storytelling is the superpower, and origin stories seem to be very important for humans.

And Sapiens, and now Unstoppable Us, is another version of the human origin story, harnessing itself the power of storytelling which you were able to hone with your undergraduate class in a way that’s been, again, colossally successful. I think 24 million copies of Sapiens sold. Meanwhile, I looked it up and the Bible sells 20 million copies per year in the US. So you have serious competition Yuval from another alternative origin story, right?

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah.

Rufus Griscom: But I wonder to what degree you see that as part of the purpose of this book and to many versions of Sapiens that have come out, the value of emphasizing an origin story that all homo sapiens share that can cause us to act in a way that’s more collaborative, hopefully?

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah, that’s extremely important, origin stories. Humans are storytelling animals. We think in stories. And this is something that often scientists miss. They try to influence public opinion, for instance, with statistics, with equations, with lists of facts. And usually it doesn’t work. It doesn’t work because they miss something very fundamental about humans. We think in stories, not in statistics, not in isolated facts. So if you want to get to people, you need to tell a story. Our superpower as an animal, what makes a superior to all the other animals, is not the power of the individual, but the ability of very large numbers of people to cooperate. Actually there is no limit to the number of humans that can cooperate. This is our secret of success.

And how do we cooperate with countless strangers? We do it by inventing and believing some story. Underneath every large scale cooperation, you always find a story at the basis. It’s obvious in the case of religions, but it’s also true in the case of modern economics. The most successful story ever told, despite all the copies sold by the Bible, the most successful story ever told is not the Bible, it’s money. Many people in the world don’t believe in the Bible is the world of God, but there is hardly anybody who doesn’t believe in money. And money is also, it’s just a story. I mean, it is not an objective reality.

We talked about food. So a fig or a banana, this is an objective reality. It has biological value. You eat a banana, you get energy. Money is not like that. If you are stuck on a deserted island with a pile of dollars, you will starve. You can’t eat the dollars, you can’t drink them, they’re useless. They’re just worthless pieces of paper. And in fact, today in the world, most money, most dollars are not even paper. Most money, more than 90% of money today in the world is just electronic data. And a lot of you got talking about Bitcoin. Even the dollars, most dollars, they are just electronic data passing between computers.

And how does it work? It works on the basis of a story. You have the greatest storyteller in the world, which are not historians and they are not the people who win the Nobel Prize in literature, it’s the people who win the Nobel Prize in economics. They’re really the greatest storytellers. And the bankers and finance ministers, they tell us a story that this piece of paper or this bit of information, it is worth 10 bananas. And as long as everybody believes that this piece of paper is worth 10 bananas, it works. I can go to a store, give this piece of paper to a stranger I never met before and get my bananas. So this is also a story.

And yes, origin stories, as you said, are very, very important. They explain who we are. Unfortunately, in many parts of the world, maybe in most parts of the world, the origin stories tend to be very narrow. They tell about the origin of just one human group, not of humanity as a whole. And I mean, looking at all the nations and religions today in the world, they are very recent. I mean, the oldest nations in the world, I don’t know, like Egypt, let’s say, it’s a continuation of Ancient Egypt, it’s about 5,000 years old. It may sound like a lot, 5,000 years, but there have been humans on earth for more than two million years. So these origin stories are not really origin. They’re very, very late. They’re telling us about just the last hour, the last minute in the life of our species.

And when you go back, you find really fascinating things about where we came from. For instance, that even though we are homo sapiens, that’s our species, almost all of us carry also DNA from other human species that once lived on earth alongside Homo sapiens. If we go back 50,000 years, we are not the only humans on earth. There are at least five other human species at the time living side by side with us. The most famous of them are the Neanderthals. And some people, when they hear about ancient species, they tend to arrange them in a line, as if at any moment in time, there is just one human species on the planet. Because we are used to this situation that there is just one human species.

Trending: Best Happiness Books of 2025 (So Far)

But actually, if you look at all the other animals, it doesn’t work like that. You look at birds, there are many species of birds on the planet right now living side by side. You have grizzly birds and polar birds and brown birds and panda bears side by side. So this was also the case with humans. We have different species of humans. And we know that around 50,000 years ago, sapiens and Neanderthals interbred, thinking about it in concrete terms, not in the abstract. 50,000 years ago, there was a child whose mother was a sapiens and whose father was a Neanderthal. And that’s really mind boggling. And we are the descendants of that child.

So with all the controversies today about mixed marriages and different family structures, and people have issues if two people from a different religions or ethnic groups have a kid together. But there you have different species, in a way, different animals having a kid together and we are the descendants of that kid.

Rufus Griscom: It’s so astonishing. And we’ve learned so much, haven’t we, in recent years, right, about a large portion of us have several, 2-3% Neanderthal in us. My favorite is the detail of the people from the island of Flores, I learned additional details from Unstoppable Us reading with my son, who were no more than three feet tall and weighed 55 pounds because they’d been isolated on this island and had, over time, there’d been dwarfism, which happens on islands, as you explain.

And my favorite detail, they hunted miniature elephants. But it’s so astonishing that we coexisted with these species. And I love the question that you pose in both Sapiens and Unstoppable Us about how our history would’ve been different if we continue to coexist with these other species. We might feel a little less special, a little less disconnected from the rest of the planet. It’s such an interesting thought experiment.

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah. I mean, just imagine, you have all these religious conflicts and ethnic conflicts. Just imagine the world with several human species still coexisting. So let’s say in the United States, in addition to all the divisions between Republicans and Democrats, between white people and black people, you also had this huge Neanderthal population. What do you do with it? I mean, what would be the position of religions? You have all these stories that after you die, you go to heaven or hell. What if you are a Neanderthal? Can Neanderthals enter heaven. And if you’re a wicked Neanderthals, do you go to hell?

The Catholic Church, for instance, have a very clear view on chimpanzees. They have been asked a number of times about chimpanzees and they said, “No. No chimpanzees can enter heaven. And no matter how wicked the chimpanzee you are, you don’t go to hell. Because you don’t have an eternal soul, when you die, you die. That’s it. There is nothing left of you.” Now, what would the Catholic Church have made of Neanderthals? Do they have an eternal soul? If they say no, then again, imagine this kid 50,000 years ago, this kid has a sapiens mother and Neanderthal father. So the Catholic Church tells him, “Okay, if you go to heaven, you can meet your mother but not your father. He has no soul.” What does it mean that my mother has a soul but my father doesn’t have a soul? Do I have half a soul?

If there were Neanderthals in the world, I think that you would have seen completely different religious ideas. Similarly with politics. I mean, can Neanderthals vote in the elections? Can they be elected to Congress? Can they be President? And the thing is that they actually build a bridge between us and the rest of the animal kingdom. As you said that if there is another human species out there, we can no longer feel completely alone and isolated and see ourselves as distinct from nature, from the other animals.

Just think how much chimpanzees have changed our view of ourselves. I think one of the most powerful books I’ve ever read which completely changed my worldview was Chimpanzee Politics by Frans de Waal.

Rufus Griscom: Oh yeah.

Yuval Noah Harari: Which describes the politics of a chimpanzee band. I think, at some point, it was a recommended reading for new Congress members in the US. And it’s fascinating. And when you read the book, you immediately understand we are not so special. Many of the things that characterize us, even that we cherish, we share with the chimpanzees. And this breaks down a huge, huge barrier.

Rufus Griscom: You’re much more explicit than many writers I’ve read on the topic of the early sapiens quite possibly engaging in acts of genocide against these other species, right? And we know that we almost certainly wiped out all the extraordinary megafauna, these beautiful animals in Australia and in the Americas. Do you think there’s a resistance to the idea that early humans were capable of large scale acts of cruelty? I mean, I think there’s some camps maybe that would prefer a version of early humans that was a little more pure.

Yuval Noah Harari: It should be clear that when we talk about our ancestors, Homo sapiens driving to extinction other human species, we are not talking about a 20th century genocide with concentration camps and mass killings.

Rufus Griscom: Yeah, sure.

Yuval Noah Harari: It’s more of competition over resources that sometimes flares into direct violence. And new sapiens tribe arrives on the scene in a place inhabited by Neanderthals or by some Denisovans or some other human species. The sapiens are better organized, they can cooperate in larger numbers. This is their big advantage. So they take most of the resources. If the Neanderthals resist, there is violence. Maybe they drive the Neanderthals away except for maybe one or two Neanderthals that join the sapiens band. And this happens again and again in more and more places until the Neanderthals become extinct. So this is the kind of process that we are talking about.

There is a lot of resistance to this idea that, from the very beginning, our species was responsible for such large scale ecological crimes, that we are basically ecological serial killers, that we have driven to extinction all our closest relatives, the other human species, and also many of the large animals of the world, even before agriculture. I mean, some people think that the damage that humans do to the ecological system, it’s a new thing, that it’s just because of industry, modern industry, because of modern capitalism, because, I don’t know, of western civilization, and they have this image that indigenous cultures in ancient times, they lived in complete harmony with nature. And this is not true.

We would maybe like it to be true. Then the problem is, our species is just actually a problem not with the species, but with the specific modern culture. But the evidence points in the other way, that there were huge, massive extinctions of animals, especially large animals caused by humans who reached America and Australia and other parts of the world tens of thousands of years ago. It’s estimated that before the agriculture revolution, we’re not talking about modern capitalism and modern civilization, we’re talking about before agriculture, before you have villages with wheat-fields, already humans drove to extinction about 50% of the large animals of the world, most notably in Australia and in America.

Before humans came to America around 15,000 years ago, 20,000 years ago, America was full of mammoth and mastodons and camels and horses and lions and all kinds of animals that are completely gone. So we don’t even know how they looked like.

Rufus Griscom: Giant sloths. They were giant sloths and dire wolves. They’re just extraordinary animals. And as you point out in the book, they didn’t have the benefit of evolving with humans over time and learning to fear them.

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah. That’s a very interesting point that you actually need a lot of time to learn to fear something. And we can learn it from our own experience, that many people today are afraid of scorpions and spiders and snakes. I personally, as a child, was terrified of spiders, even though spiders hardly kill anybody. I mean, how many people die every year from a spider bite? Very, very few. But almost nobody’s afraid of cars.

Rufus Griscom: Right. Right. Yeah, yeah.

Yuval Noah Harari: And every year, cars kill more than a million people around the world. So we don’t have to teach our kids to fear spiders, it comes naturally to them, actually very often the opposite. We need to tell them, “No, it’s not so dangerous. Don’t be so afraid of the spider.” But we do need to invest a lot of effort in teaching kids to be afraid of cars. Now why is it? It’s because spiders have been around from millions of years, so again, it’s built into us to be cautious at least about spiders and scorpions and things like that. Cars were invented a little over a hundred years ago. It’s not enough time to build this instinctual biological fear of cars.

Rufus Griscom: Interesting. Yeah. Yeah.

Yuval Noah Harari: And the same thing happened to the large animals of the world when humans spread. The animals of Africa, they grew up with these dangerous apes and they learned, even though humans don’t look very dangerous, we can’t run like cheetahs, we don’t have big teeth, we don’t have sharp nails, we’re not poisonous, but elephants in Africa learned that these apes, they don’t look dangerous, but they are the most dangerous thing around. So they learned to keep their distance. This is why there are still elephants in Africa. But when sapiens spread from Africa very quickly to other parts of the world, the big animals there, they didn’t have enough time to learn to fear us and they got extinct before they understood what hit them really.

Rufus Griscom: One of the things that I loved about reading Sapiens and that was rekindled in reading Unstoppable Us, is that I’ve always been fascinated by this question of what it felt like to be a hunter gatherer. And I suspect that you may have this feeling as well because there’s a passage in Sapiens that’s so lyrical and beautiful on this topic that I can’t resist reading it to you.

You write, “At the individual level, ancient foragers were the most knowledgeable and skillful people in history. Foragers listened to the slightest movement in the grass to learn whether a snake might be lurking there. They carefully observed the foliage of trees in order to discover fruits, beehives, and birds nests. They moved with a minimum of effort and noise and knew how to sit, walk, and run in the most agile and efficient manner. Varied and constant use of their bodies made them fit as marathon runners. They had physical dexterity that people today are unable to achieve even after years of practicing yoga or tai chi.”

There’s a sense of reverence there, in your words, I think, Yuval. Do you have a longing for this moment when humans were in the environment in which we evolved? Or would you describe it more as just a curiosity?

Yuval Noah Harari: Well, I think, in a way, almost all of us have this longing that something inside us remembers the Stone Age and sometimes wants to go back there. If you wake up in the morning and you wish, “Oh, I wish I didn’t have to go to the office,” or as a kid, “I wish I didn’t have to go to school and I could go to the forest instead and look for mushrooms and fish in the river,” then this is a part of you that remembers how we lived in the Stone Age. And we lost a great deal since that time. Of course, we also gained many things.

I mean, it wasn’t idyllic, it wasn’t utopia, but many dangers. A tiger could come and eat you. You’re constantly bothered by mosquitoes and insects. You can’t hide inside your house and close the window. And, I don’t know, you climb a tree to pick fruits, you fall down, you break your leg, this could be a death sentence. I mean, there are no hospitals. The band has to move on to the next valley, to the next camp, and maybe they can’t take you with them. So it was not a comfortable life, it was not always a pleasant life. But certainly, we have lost a great deal on the way from the Stone Age to the Silicon Age.

Rufus Griscom: We had David Wengrow on the show to talk about The Dawn of Everything a few months ago. Extraordinary book.

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah. I think it was the best book I’ve read this year.

Rufus Griscom: Yeah. Right? Right? Just remarkable. And of course, I loved all the descriptions of the sophistication of Native American life and politics and so on. Now, of course, you certainly know that the Davids, as we called them, take aim at you and the other big history writers for—

Yuval Noah Harari: Yes.

Rufus Griscom: … perpetuating a false origin story. They believe this notion that we lived in small egalitarian bands, then the agricultural revolution was a one-way street to hierarchical structures that exploited peasant farmers. They make the case that in contrast, I’m quoting them here, “The world of hunter gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiments resembling a carnival parade of political forms. Agriculture did not mean the inception of private property, nor did it mark an irreversible step towards inequality. In fact, many of the first farming communities were relatively free of ranks and hierarchies.” Do you buy this? What’s your take on this criticism?

Yuval Noah Harari: Well, I completely agree. I think that they exaggerated the difference between what they say and what many of the previous researchers have said. I think that most researchers of hunter gatherer societies and of the Stone Age except that there was a very wide variety of social arrangements in the Stone Age and in the hunter-gatherer societies even after the agricultural revolution. My main point is that the human superpower is the ability to cooperate in large numbers. The way that I explain how Homo sapiens manage to overcome the Neanderthal and managed to spread all over the world is not because they lived in these tiny isolated bands, but because they were able, already tens of thousands of years ago, to unite at least in [inaudible 00:37:32] many bands into larger, more complex structures of tribal structures. And similarly, when the agricultural revolution came, it didn’t force all people into a single social structure.

What you do see, however, and this is something that I didn’t really understand the alternative thesis that the Davids try to present, is that even though the first agricultural societies were indeed sometimes very small and could be very egalitarian and so forth, over time, over thousands of years, all over the world, you see the emergence of larger and larger agrarian societies culminating with cities and kingdoms and empires. And even though, of course, everywhere you still have these small societies on the side, they tend to be crushed and conquered by the kingdoms and empires over time. So that in the end, these kingdoms and empires conquer the entire planet.

And I don’t see how you can posit an alternative history to that. You can argue about what are the political implications. Now, I hope I don’t misrepresent what they say, but their basic, I think maybe the most important message is that you can build a large scale society, which would be truly egalitarian, that people will enjoy freedom even in a large scale society. Nobody disputes that in a small scale society, you can have freedom and equality. The question is always about the large scale societies, society, say, of millions.

And I was eager to see what are their examples of a free large scale society? No. You know, the usual suspects are the modern democracies. If you don’t like the United States, okay. So you go for Canada, you go for Denmark. “Oh, this is the perfect society.” And no, they say that even Denmark is an oppressive regime.

Rufus Griscom: Yeah.

Yuval Noah Harari: So what are their examples? And they don’t really have convincing examples of large scale societies. I’m talking about hundreds of thousands, millions of people living together that fit the bill. They give some example from ancient societies about which we don’t know much. So they bring Teotihuacan in Central America, and we don’t really know the social structure and the political structure of Teotihuacan. They spend a lot of time arguing that Teotihuacan was not ruled by kings. Even if we accept it, Denmark is also not ruled by kings, the United States is not ruled by kings, the Soviet Union was not ruled by kings, it didn’t make them a free society, at least not according to their standards.

Similarly, they point out that Teotihuacan, based on archeological evidence, had public housing. You know, this is debatable. The archeological evidence can be interpreted in many different ways. But let’s go along with it. Let’s say Teotihuacan had public housing. The Soviet Union also built public housing. It didn’t turn it into a free society. So you’re left with the impression that if even Denmark doesn’t fit the bill, that there has not been a single free large-scale society in history. So you are only left with a promise of some future utopia that maybe one day we can build it, which is fair. But as a historian, it’s a weak argument if you can’t point to a single successful experiment in the whole of human history.

Rufus Griscom: Yes. Yes. And utopianism can distract us from the unglamorous business of incrementally improving the place we already are. You describe currencies, corporations, nations, and religions as fictions, which is a wonderful, simpler way of describing how these different entities function. What’s more surprising is when you go on to say that liberalism is a secular religion, it’s a kind of fiction, and that the idea of human rights is a fiction. That becomes more, I think, surprising to a lot of readers. But you also say, I think, that among fictions, liberalism includes a willingness to be wrong, a humility that’s maybe somewhat a product of the scientific revolution. Among available fictions, do you see-

Yuval Noah Harari: Absolutely.

Rufus Griscom: … liberalism is better than the others? Yeah.

Yuval Noah Harari: Absolutely. When I say something is a fiction, it means that it’s something that exists in our imagination, that we invented it. Now, for many people, this is obvious about Gods, this is obvious about money, but it’s the same with human rights. I mean, human rights are not an objective biological fact about humans. We don’t have rights inscribed in our DNA. They don’t come from biology. This is something that we constructed in our imagination that, it actually is that humans don’t have rights, they should be granted rights.

And what is crucial about liberalism is that it is willing to admit its own limitations, its own mistakes, which is the first step towards improvement. When you compare the American, let’s say, Constitution to the 10 Commandments, both documents originally endorsed slavery. Many people don’t know this or don’t realize it, but the 10 Commandments endorsed slavery. You just need to look up the 10th commandment. The 10th commandment says that thou shall not covet your neighbor’s house or your neighbor’s field or your neighbor’s slaves. If you read the 10th commandment, it’s perfectly okay to have slaves. What’s not okay is to covet your neighbor’s slaves. This is wrong. You’ll go to hell if you do that.

Trending: Why Rest is the Biggest Productivity Hack for Your Brain

And of course, the American Constitution also endorsed slavery. But the amazing thing about the American Constitution, which is one of the most revolutionary document in human history, it includes a mechanism to amend itself. It has a way that the founders… It’s very common today to disparage the American founding fathers, but to say one very important thing in their favor, they realized they are not perfect. They realized they might be making mistakes, so they provided the people who would come after them with a mechanism to identify and correct these mistakes.

And eventually, the Constitution was amended to abolish slavery, which is not true of the 10 Commandments. We still have the 10 commandment in its original form endorsing slavery. And there is no mechanism in the Bible, in Judaism, in Christianity, how to amend the 10 commandments or how to amend any of the other commandments, any of the other basic ideas of monophasic theology if it turns out that there is a mistake there. And this is the huge advantage of liberalism, that it is aware of the fact that it is a human creation, in a way, that it comes from our imagination or from our mind, and therefore it might contain mistakes. It makes no claim to infallibility.

And I think this is the most we can accomplish as human beings. We can’t create a perfect society, but we can create a society which is humble enough to admit that it’s not infallible, and to have mechanisms to correct itself. And this is the essence of democracy. Democracy is all about admitting fallibility, that every now and then we can say, “Hey, we made a mistake. Let’s try something else.”

Rufus Griscom: Well, despite this self-correcting mechanism in the US Constitution, our American experiment has been feeling particularly fragile lately.

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah.

Rufus Griscom: And I was interested to hear you say that you see the actual ideological differences between Republicans and Democrats in the United States today as smaller than they were in the 1960s and maybe other times in the past, because it sure doesn’t feel that way on the ground. When you dig into specific policy differences, I see your point, do you want to make this case that actually our differences are smaller? And how is it that we can have comparatively small ideological differences and yet be unable to talk to each other?

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah. That’s the big question. I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t know. We still need to research that. But this is really striking from historical perspective because, from the outside, the differences between Republicans and Democrats don’t seem so big, not in terms of policy or of ideology. Certainly they’re smaller than what they were in the sixties. Many of the arguments about LGBT rights and about the whole issue of transgenderism and about sexuality in general, they are really the aftershocks of the big bang of the 1960s of the sexual revolution. The issues in the 1960s are much, much bigger.

Similarly, if you think about race and the struggles in the sixties, it’s the middle of the Cold War, there is the Vietnam War, on any moment, there might be a nuclear war, as the Soviet Union, in a way, much bigger controversies and also a lot more violence. There was a lot more physical violence in the streets, riots, political assassinations, much more common at least so far than what we see in the United States today.

And nevertheless, people did not dispute, for instance, the outcome of elections. When they lost, they lost. They acknowledged it. So what’s happening right now, it’s hard to understand it if indeed the ideological differences are smaller. And yet in many ways, the Republicans today are more liberal than Democrats were in the 1960s. Not on all issues. Abortion, for instance, is an outlier here. But again, going back to LGBT rights, the Republicans today are far more liberal than the Democrats were in the 1960s.

Rufus Griscom: Interesting. Yeah.

Yuval Noah Harari: So what is really driving the levels of really hatred and fear that we are seeing today? It’s hard to explain. One dominant explanation is that it’s not about the ideas, it’s not about the policies, it’s about the technology. That new information technology has undermined the democratic system. And this makes sense because democracy is built on top of information technology. This is something that we often don’t appreciate. We think that democracy is mostly about certain ideas.

But again, going back to what we discussed earlier, we don’t have any examples of large scale democracies before the rise of modern information technology. All the examples people bring of democracy in the ancient world, they are all of very small scale societies, either hunter-gatherer societies and small towns or city states like Athens or Rome. Because in a place like ancient Athens, even though just 10% or 30% of people have political rights, we’re still talking about thousands of people, they can all come together in one place and have a political discussion. This is something you can’t do on a level of an entire kingdom or empire before the rise of modern information technology. First of all, newspapers and the printing press, then you have telegraph and radio and television.

In the Roman Empire, you could not have a democratic discussion because people just couldn’t talk with one another from different places in the empire. It became possible only with modern information technology. So democracy is built on specific information technology. And now we are living in the middle of an immense revolution in information technology. And this may be the root cause, not any disagreement about some idea or policy, of the upheaval we see in democracy, not just in the US, but in many other countries as well. In my country, in Israel, we have the same issues. In Brazil, they have the same issues and so forth.

But democracy in essence is a conversation. It’s the ability to have a conversation. And when the technology used for the conversation changes, it creates a crisis. What we see now is that people just can’t hold the conversation anymore. They are locked inside echo chambers, unable to talk with people on the other side. And we see levels of hatred and fear that previously we saw only between hostile nations. I think it’s fair to say that today, Republicans and Democrats fear each other and sometimes hate each other more than they fear or hate any other people on the planet, more than they fear and hate the Russians or the Chinese or anybody else.

This partly has to do with social media. We have people like Elon Musk describing Twitter and then social media as the town square, but it’s not the town square, it’s the gladiator arena.

Rufus Griscom: Yeah, that’s right.

Yuval Noah Harari: In town square, people listen to each other and there are the rules of civility of how to conduct a public conversation. And very often, if you start shouting and abusing and fighting, you don’t get positive feedback in the town square. But in the gladiator arena, you get a lot of positive feedback for that.

Rufus Griscom: Yeah, interesting.

Yuval Noah Harari: We have now a button for attention, basically. And unfortunately, the easiest way to grab people’s attention is by pushing the hate button, the anger button, the fear button. If you say something middle of the way, moderate, you don’t get much traction.

Rufus Griscom: Yeah.

Yuval Noah Harari: If you say something extreme, you get a lot more traction. And we basically destroy the ability to have a conversation.

Rufus Griscom: I heard you say before the midterm elections that you thought there was something like a 20% probability that democracy in the United States could fail. That’s an alarmingly high number. Do you still feel that way?

Yuval Noah Harari: Yes. The main issue, again, it’s not the policies of the different parties. The main issue is the willingness to accept the basic rules of the game. The most basic rules of the election is that if you lose, you concede. And this is now up for grabs. This simple rule is no longer accepted by everybody. It’s like playing football, now with World Cup. It’s like playing football, when you say, “Okay, if I score a goal, that’s one for me. But if you score a goal, that’s zero. We don’t accept that. Only we can score goal.”

You can’t play football like that. And similarly, you can’t have a functioning democracy if increasingly, when you lose, you refuse to accept the response of the election. And we have, unfortunately in the US and also in other countries, more and more politicians who say openly that I will accept the results only if I win and people still vote for them.

Rufus Griscom: Yeah.

Yuval Noah Harari: In this case, you cannot maintain democracy for long. And even more fundamentally, democracy works only if you view the other people, the other side, as your political rivals but not as your enemies. It’s fine to have rivalries and to have disagreements. This is what democracy is all about. But if you view the other side as your enemies who are out to destroy you, then democracy cannot survive for long. In such a situation, you will do anything to win the elections, and if you lose, you don’t accept the results.

So if you view the other side as your enemies, you can have a civil war, you can split the country, or you can have a dictatorship. Again, we should realize democracy is not like gravity that you have it everywhere. No. Especially in large scale societies, democracy is a very difficult system to build and to maintain. Under many types of conditions, it is simply impossible. The idea that you can have a democracy anywhere, anytime is simply completely wrong. You need very special preconditions for a successful democracy. And if you lose one of these preconditions, for instance, in a place where people see the rivals as their enemies, you just can’t have a democracy.

Rufus Griscom: And as you said, it’s easy to lose democracy and it’s very hard to get it back. We had Will MacAskill on the show recently, and as you may know, he’s part of this longtermism movement. And one of the arguments he makes is that we have periods when our values or social structures are up for grabs. And then long periods during which there’s, what he calls a valued lock-in, that you have a new structure that could be in place for potentially very long periods of time. And that makes the next couple decades potentially very high stakes. Do you have a view on the longtermism movement and Will MacAskill?

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah. I think, of course we should think in long term, not just in short term. Many of the big dangers we face are not immediate. It’s not the next year or the next two years. We need to think in terms of at least decades. Climate change is one obvious example. Artificial intelligence is another obvious example. I don’t think that, in a science fiction scenario, that we have killer robots tomorrow morning running in the streets, killing people. This is not going to happen.

But artificial intelligence is one of the biggest threats to human civilization. It’s the first technology in history that can make decisions by itself and can therefore take power away from us. Every previous invention in human history always empowered humans, whether it’s a knife, a stone knife, whether it’s an atom bomb, it empowers us in the sense that we make the decisions how to use it. It cannot make decisions by itself. AI is the first technology that can make decisions by itself. Autonomous weapon systems are different from atom bombs. They can decide by themselves who to shoot, who to kill.

Similarly, I don’t know, a recommendation algorithm or the algorithms that run Twitter and Facebook and Instagram, they are not like radios and printing presses. Printing presses could never decide what to print. There was always a human in the loop deciding, “Okay, let’s print the Bible. Let’s print Copernicus’s book. Let’s print Newton’s book.” There is always a human making the decision. Now increasingly, and this goes back to the previous issue of having a conversation, our conversations are regulated, are moderated and monitored by algorithms, not by human beings. We are losing control of our lives.

Increasingly, more and more decisions about our lives are taken by algorithms. You apply to a bank to get a loan. Increasingly, it’s not a human being that decides whether to give you a loan. It’s an AI that collects data on you and decides whether to give you a loan. And when the bank refuses to give you a loan and you ask the bank, “Why not? What’s wrong with me? Why didn’t you give me a loan?” And the bank says, “We don’t know. Computer says no. The algorithm told us you are not credit worthy, so we just believe our algorithm.”

The AI revolution is just 10 years old. We haven’t seen anything yet. We have to be extremely concerned about the dangers inherent in this technology. It can do also a lot of good, of course. But if we are not careful, it’ll create the worst totalitarian regimes in history. Things far worse than what we saw in the 20th century with the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany and so forth. The Soviet Union couldn’t follow all the citizens all the time. They just couldn’t. You can’t have a KGB agent following every Soviet citizen 24 hours a day. And even if you do, I mean the KGB agents, they just write their paper report on you, which is sent to headquarters in Moscow, and there is nobody there who could read all the report and make sense of them.

Now with smartphones and cameras and drones and all that, you can follow everybody all the time. And you have AI to analyze all the data. So it is technically possible for the first time in history to follow everybody all the time. And this creates the potential for the worst totalitarian systems in history. And this can happen in 10 or 20 years. We have to be extremely concerned about these issues.

Rufus Griscom: This is a new idea for me. It’s so interesting, this interdependence between technology and systems of government. It hadn’t really occurred to me until you said it just earlier, that we needed the printing press to have large scale democracies, that different forms of government require and benefit from different forms of technology. This could quite possibly make us very concerned about the evolution of a country like China that’s embracing all the latest technology and how artificial intelligence combined with surveillance technology maps onto a country like China and potentially the empowerment of AI, how that could make such a state that much more powerful.

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah, absolutely. Because in the 20th century, the story was that in the battle between totalitarianism and democracy, democracy won. Why? Because totalitarianism just wasn’t efficient. The Soviet Union tried to run a central economy from Moscow. And it just wasn’t efficient. They didn’t have the capacity. They brought all the information to Moscow, but there was nobody there who could process all the information fast enough and efficiently enough to make the right decisions. And this is why the distributed information system of the United States proved to be far superior to the centralized information system of the Soviet Union.

The thing is that it’s not a law of nature that in all cases, under all conditions, a distributed system, a decentralized system is always more efficient than a centralized system. This was true in the second half of the 20th century. Now, AI is changing the situation. And the Chinese, they’re making a huge historical bet that AI will make centralized systems more efficient than decentralized systems. And we don’t know what the outcome of this new round in the contest between democracy and totalitarianism will be. Technology really changes the fundamental situation there.

Trending: How to Break Free From the Ambition Trap

Rufus Griscom: It’s terrifying. Yeah. And when you think about facial recognition and potentially health monitoring, clothing, and I have a watch and a ring that monitors my pulse, all of which is connected to my wifi, right? And one can imagine scenarios that even George Orwell could not fully have conceived of.

Yuval Noah Harari: Exactly. Because I think the most frightening thing, I think, of everything about this technology, the most frightening thing is the ability to go under the skin with outside surveillance. Because in the 20th century, and even in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, surveillance was always above the skin. That in Stalin’s day, they see where you go, they see who you talk to, they listen to what you’re saying, but they don’t really know what’s happening in your mind, what you actually feel.

So you have this big meeting and the Stalin gives a speech, and everybody’s of course, smiling and clapping their hands and enthusiastic. If deep inside your heart you say, “You go to hell. I hate you, Stalin.” But on the outside, you are smiling and clapping your hands, you are okay. But in the 21st century, the future Stalins, and we already have a number of dictators who want to be the next Stalin, they will have the technology to actually go under the skin with these things like the watches and the bracelets that measure your heartbeat and your blood pressure.

We are not there yet. But say in 10 years or 50 years, we might be in a situation when if you live in a place like North Korea or some other totalitarian regime, you are obliged to wear these surveillance tools on you all the time. And this can be used to know what you are feeling and thinking. And this is terrifying. And this is not science fiction. We are developing the technology that can do that. Of course, it should be very, very clear that this is not a prophecy, it’s not deterministic, it’s not inevitable. I don’t believe in technological determinism. Technology always gives us a spectrum of choices.

When people invented knives, you could use a knife to murder somebody, you could use it to save their life in surgery, you can use it to cut salad. Similarly, in 20th century, the technology that was used to build the Soviet Union is basically the same technology that was used to build the United States. Both the Soviet Union and the US, they used trains, electricity, radio, telephone. So there is nothing inherent in the technology that forces you to use it to build totalitarian regime. It just makes it possible.

And it’s the same in the 21st century. If we are not careful, then AI and bioengineering and all that will be used to create the worst totalitarian regimes ever. But if we make the right decisions now and in the coming years, then they can be used to create the most open democratic societies. And AI will be used to monitor not the citizens, it’ll be used to prevent government corruption and bioengineering will be used not in order to, I don’t know, upgrade some tiny elite, but actually to provide better healthcare for everybody. So that’s a choice, and I hope we make the right decisions.

Rufus Griscom: What specific steps do you think we can take to properly manage the development of AI? I mean, do we need to slow it down? Right now, just in the last few weeks, ChatGPT was released. Everybody I know is currently having conversations with language models. And it’s one of these inflection points, not unlike the release of the first smartphone 15, 16 years ago, where you just feel that something is fundamentally changing and you’re watching it happen and we’re not in full control of the reins.

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah. I think, first of all, the two basic assumptions we should start with is that we haven’t seen anything yet. This is just the first tiny baby steps of AI. In recent years, I’ve heard people say, “You know, they say that AI can do this, can do that. No, it can’t. I’ve tried, it can’t do that.” And this is ridiculous. I mean AI, real AI is basically something like 10 years old. This is just the beginning of the revolution. So we have to take into account that this is going to go much further than what we’ve seen so far.

And secondly, that there is always a choice, that no technology forces us in a specific direction. So we shouldn’t believe the kind of technological determinism that sometimes people in the Silicon Valley have, that we do it because this is the only thing that can be done with this technology. And if we don’t do it, the Chinese will do it. So we have to do it. This is not true. In the previous wave of revolutions, like in the industrial revolution, we had big industrialists telling people that we must send kids to work in coal mines. They sent 10 year old kids to work in the coal mines. And when people questioned it, they said, “It has to be done. If we don’t do it, the Germans will do it and they will get ahead of us.”

Now we know that this was nonsense. That it was better on all levels to send the kids to school and not to the coal mines. So we should be skeptical about this determinism. And there are many regulations that we should have about AI. I don’t have a lot of time. I’ll just mentioned a few of the key principles. First of all, when you collect information on me, this information should be used only to help me, not to manipulate me.

This is very obvious. We have it in place in other systems. Like my personal physician has a lot of very private valuable information about me. They are not allowed to sell my information to a third party or use it to manipulate me. It should be the same with Facebook and Google and the other tech giants. “Okay, you have my information, you cannot use it to manipulate me or to sell it to somebody else.”

Secondly, whenever we increase surveillance of individuals, we must simultaneously increase the surveillance of the big corporations and the government. You know more about me, I must simultaneously know more about you, your business model. How do you make your money, actually? How do you pay your taxes? And same with the government. And also another key principle, never allow all the information to be concentrated in one place. This is the high road to totalitarianism. It doesn’t matter if the one place where all the information is, is a government agency or a private corporation. Both are equally dangerous. We should just prevent the over concentration of information.

And one last point… Again, each of these points is worth an entire book. But one last point is that, whenever AI is used to make decisions about humans, it should leave room for humans to change. Because the tendency of AI is to assume that humans don’t change. It’s much easier to make decisions about humans when you assume they don’t change. To give just one example maybe, like movie recommendations. Like Netflix recommends us which movie to watch. It’s much easier for the algorithm if it assumes that humans have a fixed taste in movies, so it constantly gives us movies of the same type. It also makes it easier for Netflix to know where to invest its money, continuing to produce the same movies that we watched last time.

But this is not good for humans. Because it means it narrows our artistic capabilities, our taste. So AI, even on something as simple as recommending movies, should always assume humans change, humans can develop. So I shouldn’t just recommend to them the same type of movies they watched before. I should help them expand their horizons. This of course is more difficult. It also is more difficult than for the company to know where to invest its money. It can invest billions in another superhero movie, but now people have changed their tastes, so they wasted their investment. But for humans, it’s good.

So AI should always assume the capacity of humans to change, and would actually help us to change. I think the best vision for AI is not a rivalry or a battle between AI and humans, but rather a cooperation in which humans help AI to improve. And at the same time, AI helps humans to improve and to learn and to change.

Rufus Griscom: I’d love to end, Yuval, with a more personal question, which is…

Yuval Noah Harari: Yes.

Rufus Griscom: There’s a lot of stressful ideas here for the average listener.

Yuval Noah Harari: Absolutely.

Rufus Griscom: And it’s so difficult for so many of us to distinguish between the small problems or the big problems. I mean, as individuals, we struggle on a daily basis with obnoxious drivers, the spouses, dishes in the sink, office politics. It’s always struck me that if you don’t have big problems, the small problems become large problems. It’s helpful to see the big problems, I think, maybe to put things in perspective. But I wonder how we avoid the noise, how we take joy in being humans in a world that’s feeling increasingly like it’s speeding past the human level experience?

And I know that meditation is an important part of your experience. Maybe that helps you to attain this sort of 10,000 foot view and keep things in perspective. Is this something we should be doing? And how do you think about how to, as individuals and as a society, how do we keep things in perspective?

Yuval Noah Harari: Yeah. For me, meditation is very helpful in this. It helps me keep my mind more balanced. But different things work for different people. For some people, it’s therapy. For some people, it’s sports or art. What is common to all of this is that we are now flooded by enormous amounts of information. And you have the smartest people in the world working on how to constantly get our attention to the smartphone, to the screen, to the next thing. And we are living really within a toxic information environment. The same way we pollute the atmosphere, we also pollute the information sphere.

And I think we need to go on an information diet. Many of us are very careful about the food we put into our body. We also need to be extremely careful about the food we put into our mind, the information that we consume. When you go to the supermarket and you buy some food, you often have this label on it, “This contains 40% sugar, 20% fat.” If you want it, you can have it. But at least you know what you put inside your body. We need this also with the information we consume. Like you watch some video, whatever, it should have, “This contains 40% hate, 20% greed.”

Rufus Griscom: Yes.

Yuval Noah Harari: This is the diet you want for your mind, then okay. What can we do? But at least you know. I’m very much in favor of disconnecting every now and then. I’m now actually talking to you from India. I’m on my way to a meditation retreat.

Rufus Griscom: Wonderful. Wonderful.

Yuval Noah Harari: Where I completely disconnect for a time from everything. No phones, no computers, no emails, no nothing. Just give the mind time to detoxify. And also, I write books. I read books. I write books. Books demand a long span of attention. It’s not 10 seconds or a minute. Even the children’s book, even an Unstoppable Us, it’s a long book on purpose. I mean, there is a lot of value in learning how to immerse yourself in a story, in a journey, without allowing your mind to be constantly distracted every few seconds or every few minutes by the next thing.

Again, unfortunately, we have some of the smartest people in the world working constantly on how to distract us, how to grab our attention, and we need government regulations on this. We can’t put all the responsibility on individuals. But also individuals should resist this and should protect their mind in the same way that they protect their body from unhealthy food or unhealthy environments.

Rufus Griscom: Sam Bankman-Fried, who was running FTX, the crypto fund, apparently said that he never reads books. So I think that must explain part of the problem.

Yuval Noah Harari: This is the best recommendation for book reading that I’ve heard in a long, long time.

Rufus Griscom: Exactly. There is something about the humility of just immersing yourself in someone else’s ideas for 10 consecutive hours. That is, I think, a very, very healthy exercise. And I agree. People should have media diets with the exception of podcasts, a possible exception of podcasts.

Yuval Noah Harari: No, I’m not saying you shouldn’t listen at all, you shouldn’t be on Facebook. No. I mean, you should. But balance it. Balance the time that you’re investing it.

Rufus Griscom: Absolutely. Well, Yuval, it’s now almost 1:00 AM in New York City, which is roughly three hours past my bedtime, and yet I’m wide awake because I have so enjoyed this conversation. Thank you so much for taking time out to join us.

Yuval Noah Harari: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure. Have a good night.

You May Also Like:

- 10 Years Ago, She Predicted COVID. Here’s What She’s Worried About Next

- New Evidence Shows How Humans Really Migrated to the Americas

- The History of Humankind Just Got a Major Rewrite

To enjoy ad-free episodes of the Next Big Idea podcast, download the Next Big Idea App today: