William J. Bernstein is an American financial theorist known for pioneering research in the field of modern portfolio theory. Bernstein is also highly regarded for his self-help finance books for individual investors who wish to manage their own equity portfolios. His publications include The Intelligent Asset Allocator; The Four Pillars of Investing: Lessons for Building a Winning Portfolio; and The Birth of Plenty, a history of the world’s standard of living.

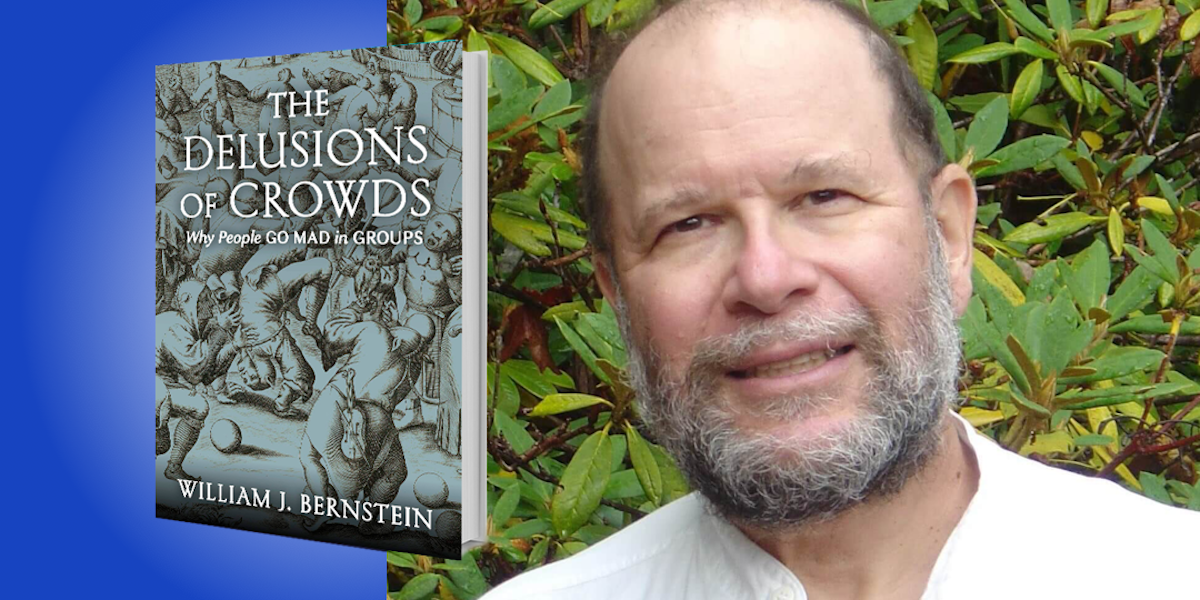

Below, William shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Delusions of Crowds: Why People Go Mad in Groups (available now on Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Old classics can often become suddenly relevant.

For the past few decades, I’ve been writing about finance and the history of economics and technology. Three decades ago, I came across a classic well-known in the field of finance, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, written in 1841 by Charles Mackay—a Scottish journalist who chronicled financial, religious, fashion, and health manias over the preceding centuries.

It’s famous among financial types because of his description of the stock market manias that swept Paris and London in 1720, as well as the Dutch tulip craze of the 1630s, bequesting the word “tulipmania” to the English language. Over the 180 years since its publication, it’s saved the bacon of many an investor by teaching them how to recognize the characteristics of financial bubbles.

When I first came across the book in the early 1990s, I didn’t find it terribly relevant to the relatively sedate capital markets of the time. But within a few short years, Mackay’s vivid descriptions of entire societies going bonkers over stock investing came alive before my amazed eyes, as my friends and neighbors suddenly bought into the notion that getting rich with internet stocks was the easiest thing in the world. For the past century and a half, those who had read Mackay’s book had seen that movie—and they knew how it ended.

2. We are the apes that imitate.

On December 4, 2016, a sadly deluded man named Edgar Maddison Welch, convinced that a cabal of Democratic Party pedophiles were engaging in satanic rituals in Washington DC’s Comet Ping Pong pizzeria, entered that establishment and fired three bullets from his AR-15 assault rifle into the ceiling. In the wake of Donald Trump’s 2020 electoral defeat, this belief in Democratic Party-associated pedophile rings mushroomed into the QAnon narrative, which held that just before Joseph Biden’s inauguration, Donald Trump would expose this conspiracy, arrest the perpetrators, and retain the presidency.

It turns out that such mass delusions pop up everywhere in human history, and the major reason for this is simple: We are the prisoners of our evolutionary history, doomed to operate in the Space Age with Stone Age minds.

“We are the prisoners of our evolutionary history, doomed to operate in the Space Age with Stone Age minds.”

To understand why we are so prone to imitation, consider that over the past fifty to hundred thousand years, the human race has spread from its home in Africa to virtually every corner of the planet, from the arctic shores to the tropics to isolated islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Crucially, our ability to adapt to such diverse environments during our species’ late Pleistocene migration from the high Arctic to the Strait of Magellan, which took only several thousand years, rested on accurate imitation.

Two evolutionary psychologists, Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson, have pointed out that during the human migration from the Bering land bridge and through North America and South America, we had to learn skills as varied, and as difficult, as constructing kayaks and poison blow guns—both of which are extremely difficult to do unless you’ve seen it done by someone else and are very good at imitation. In other words, it’s nearly impossible to make a kayak from the locally available raw materials if you’ve never seen it done before. The same is true of the very different skill set needed by an Amazon native.

Natural selection thus favored the human proclivity and ability to imitate—in other words, Mother Nature rewarded credulity. The problem with this evolutionarily selected credulity is that it is now often maladaptive, carrying with it the modern propensity, in Mackay’s famous words, to “extraordinary mass delusions and the madness of crowds.”

3. How to spot a financial bubble.

Did the recent excitement over GamesStop, Robinhood, and Bitcoin leave you puzzled and disoriented? Don’t be, because they exhibited the four characteristic subplots that accompany a bubble.

First and foremost, financial speculation dominates all but the most mundane social interactions; whenever and wherever people meet, they talk not of the weather, family, or sports, but rather of stocks, bonds, and real estate.

Next, otherwise sensible professionals quit reliable, good-paying jobs to speculate in the aforementioned assets.

“In a way, bubble investors can be thought of as capitalism’s unwitting philanthropists.”

Further, skepticism is often met with anger; while there are always some folks old enough to have seen this story before and to know how it ends, their warnings are met with scorn and ridicule.

Finally, observers begin to make outlandish financial forecasts. Stock or real estate prices are predicted to not merely move ten, twenty, or thirty percent in a given year, but rather will double, triple, or add a zero.

While the first movers in a bubble can prosper, the vast majority of those who follow usually lose their shirts. What I find interesting, though, is that while bubble investing can savage the nest eggs of millions of investors, bubbles usually benefit society at large.

Perhaps the best recent example of this was the Global Crossing story. In 1997, a former bond salesman named Gary Winnick founded Global Crossing with the goal of connecting the world with fiber optic cable. Investors large and small, intoxicated by the new internet technology, piled into the stock, inflating its market value to more than $40 billion, $6 billion of which Winnick owned. A 1999 Forbes cover gushed, “Getting Rich at the Speed of Light.”

Winnick’s forecast of the need for global bandwidth proved correct. But like many business visionaries throughout commercial history, he underestimated the two things that always diminish profits: competition, and the technological improvements by later entrants that often bury the first movers.

In the end, Global Crossing went bust, bought for literally a penny on the dollar by Asian investors, impoverishing his investors—many of whom were unsophisticated ordinary folk who lost their nest eggs. And herein lies the irony of many stock bubbles born of misplaced technological enthusiasm: However badly Global Crossing savaged its investors’ fortunes, the company endowed the planet with much of its current bandwidth. In a way, bubble investors can be thought of as capitalism’s unwitting philanthropists.

“It’s sad but true that a good story will often trump the most ironclad fact.”

4. Narratives are fatal to reason.

On March 26, 1997, police in Rancho Santa Fe, near San Diego, found the bodies of thirty-nine members of Heaven’s Gate, an end-times religious sect whose members believed that after their suicides, they would be transported off the planet by a spacecraft hidden in the tail of Comet Hale–Bopp.

Just how do large numbers of people come to believe such outlandish and deadly narratives? Not only is man the ape that imitates, but he’s also the ape that tells stories, and it’s sad but true that a good story will often trump the most ironclad fact.

Modern humans evolved only about one or two hundred thousand years ago, and our major distinguishing characteristic is our large brain, which is the key to our survival as a species; we can’t run very fast, we can’t fly, we don’t have fearsome claws or teeth, and we’re not even all that strong. So the only way we stay alive is by employing language to communicate and cooperate with each other. When a band of hunters sallied forth to hunt a large, fast, and dangerous prey, they didn’t deploy mathematical vectors; rather, they issued narrative-based communications: “You go right, I’ll go left, and we’ll spear the beast from both sides.” We thus understand the world largely through narratives, and the more compelling the narrative, the more powerful it is.

Neuroscientists believe that narratives powerfully engage our brain’s fast-moving limbic system—our evolutionarily ancient “reptile brain”—and so make an end run around our large cerebral cortex—our newer, conscious, and much slower “thinking brain.” Most of the time, we employ narratives towards useful ends: The deployment of scary stories about unhealthy diets and smoking to encourage changes in mealtime behavior and tobacco consumption, of sermons and fables about honesty and hard work that improve societal function, and so forth. On the downside, by overwhelming our reasoning system and discouraging logical thought, narratives can get us into analytical trouble.

Thus, the more we depend on narratives, and the less on hard data, the more we are distracted away from the real world. Ever lose yourself so deeply in a novel that you became oblivious to the world around you? Ever heard a radio broadcast so hypnotizing that you sat in your driveway for ten minutes so you didn’t miss the end? Psychologists call this “transportation,” and it’s fatal to reason.

“If you want to analyze a subject, stick to the numbers and facts, and ignore the surrounding narrative.”

It turns out that even when presented with compelling narratives clearly labeled as fiction, we become unable to segregate the worlds of fiction and fact. In other words, we cannot cleanly “toggle” between the literary and real worlds, as occurred after the 1975 release of the movie Jaws, which caused formerly bold swimmers to huddle close to the shoreline. Producers Darryl Zanuck and David Brown knew just what they were doing; they delayed the film’s release to coincide with the summer season. As they put it, “There is no way that a bather who has seen or heard of the movie won’t think of a great white shark when he puts his toe in the ocean.”

Psychologists have studied this “Jaws effect” by exposing people to compelling narratives, and have found that the more strongly their subjects are transported into the narrative, the more their opinions are influenced by it; critically, it doesn’t matter whether the narratives are clearly labeled as fact or fiction. Even more amazingly, the more the subject is transported into a narrative, the less able they are to perform simple analysis of its content. In plain English, a high degree of narrative transportation impairs not only the ability to distinguish fact from fiction, but also impairs one’s critical facilities.

Put yet another way, the deeper the reader or listener enters into the story, the more they suspend disbelief, and the less attention they pay to whether it is, in reality, true or false. This study, and many others like it, make this startling and cynical suggestion: If you want to analyze a subject, stick to the numbers and facts, and ignore the surrounding narrative. But if you want to convince others of something, forget the facts and data, and tell them the catchiest story you can.

5. The most compelling, and corrosive, story ever told is the one about how the world ends.

We attend more to bad news than to good news. This seems to be a patently obvious feature of human nature: Ambulances clustered around a crumpled vehicle off the road will slow traffic, whereas an intact abandoned car in the same position will not. The headline “Dozens of Miners Killed in Explosion” sells newspapers, whereas one that reads “Things Gradually Getting Better” does not.

The human preference for bad news is so widespread that “bad is stronger than good” has become one of the basic precepts of experimental psychology, and its evolutionary roots are obvious, since attending to harm and risk carries with it obvious survival value.

“Fake news stories, which are generally lurid and sensationalistic, are 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than real ones.”

Yet the compelling nature of bad news often proves dysfunctional in the digital era. One study, for example, found that fake news stories, which are generally lurid and sensationalistic, are 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than real ones. The so-called “three degrees of Alex Jones” phenomenon on YouTube has become a grim joke among media specialists: Only three clicks will separate a video on replacing your lawnmower’s spark plug and Mr. Jones raging about the Sandy Hook school massacre “hoax.”

There can be no more compelling narrative than the one about how the world ends, and the more lurid and bloody it is, the more it compels people. These narratives likely extend back tens of thousands of years, and by the dawn of written history had already become embedded in cultures around the world.

Over the last century, evangelical theologians and writers have crafted the bloody end-times narrative of the Bible’s last book, Revelation, into an ever more lurid and arresting narrative, becoming, in effect, skilled end-times entrepreneurs. Evangelical ministers such as Jerry Falwell and Jim Bakker and writers such as Hal Lindsey and Tim LaHaye have all honed their interpretation of Revelation, technically known as “premillennial dispensationalism,” into the world’s most compelling end-times story.

Its basic narrative arc goes something like this: The Jews return to Israel, rebuild the Jerusalem Temple, and there resume sacrifices. The Roman Empire then reassembles itself in the form of a ten-member confederation under the leadership of a charismatic, brilliant, and handsome individual who turns out to be the Antichrist, the earthly manifestation of the Devil, who enters into a seven-year alliance with the Jews. A complex series of alliances and betrayals ensues, followed by a holocaust, called the Tribulation, that kills billions. Christians who have found Jesus are conveniently saved from Armageddon and the Tribulation by being transported up into Heaven—the Rapture—which occurs right before the trouble starts. A third of Jews convert to Christianity and proselytize the rest of humanity and so survive—tough luck for the other two-thirds, who burn.

It’s impossible to understand the current polarization of American society without a working knowledge of the dispensationalist narrative, which strikes the majority of well-educated citizens with a secular orientation as bizarre, but which to evangelicals is as familiar as Romeo and Juliet or The Godfather. The morbid appeal of this narrative has benefited its purveyors, both in and out of the ministry; Hal Lindsey and Tim LaHaye’s books have sold more than a hundred million copies, and their Manichean division of people into camps of good and evil was on full view at the Capitol on January 6th, as the insurrectionists battered down its doors with a large wooden cross and raised their arms in ecstatic prayer in the Well of the Senate. Whether secular Americans know it or not, they are now living in a nation suffused with this mass delusional narrative, and the better they understand it, the less they will be surprised by events such as the Capitol insurrection and the takeover of a major political party by the evangelical right.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: