Michael Gervais is a high-performance psychologist. His clients range from Olympians to artists to Fortune 100 CEOs. He founded Finding Mastery, a consulting agency, and co-created the Performance Science Institute at the University of Southern California.

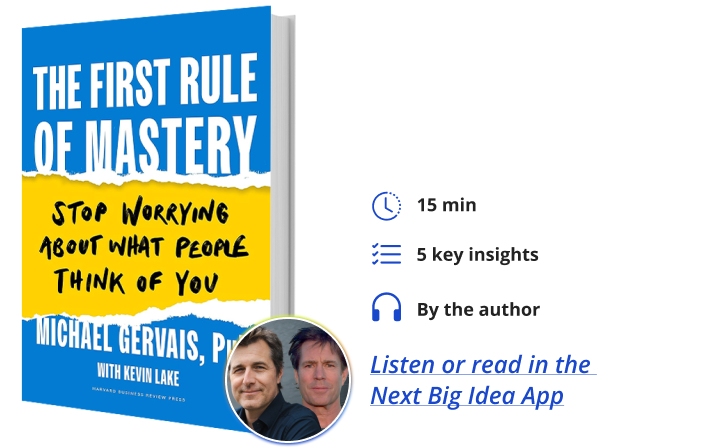

Below, Michael shares five key insights from his new book, The First Rule of Mastery: Stop Worrying About What People Think of You. Listen to the audio version—read by Michael himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The biggest obstacle to unlocking human potential.

As a performance psychologist, my role is to unlock the potential of individuals, teams, and organizations. Over 25 years working with the world’s best performers across sports, business, and the arts, I have found the single greatest impediment to unlocking human potential is the fear of people’s opinions (FOPO).

FOPO is a phenomenon so pervasive and familiar that we often don’t recognize it, even when it’s influencing our decisions, our self-worth, or our perceptions of success and failure. Just as in M. Night Shyamalan’s iconic film, The Sixth Sense, where the young protagonist, Cole Sear, has the uncanny ability to see the dead, when you tune into the presence of FOPO, you suddenly “see” it everywhere. You notice it when a colleague hesitates to voice an unpopular opinion during a meeting, or when a friend changes their outfit several times, seeking validation. You see it in the young athlete who double-checks their every move, worried about what the crowd thinks more than the game itself. You might even spot it in yourself, in the slight hesitation before posting a picture online or the anxiety surrounding how others might perceive your choices.

With FOPO, we are held hostage by the unseen, often imagined, judgments and expectations of others. The persistent rumination about what others may be thinking draws us out of the present moment, pulls resources away from deep focus on the task at hand (which is required for growth and improvement), inhibits our ability to take in new information, and taxes our energy.

2. We are social animals masquerading as separate selves.

The self-reliance myth that underpins western culture makes for great storytelling and effective branding but masks a fundamental truth: no one does it alone. Self-reliance and rugged individualism are embedded in the Western psyche, but there’s a more foundational need: the human need to belong.

In 1995, two leading social psychologists, Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary, published a landmark article suggesting that belonging is not just a desire but a need, a deeply rooted human motivation that shapes our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Baumeister and Leary posited that the desire for social acceptance and belonging may be the motive that accounts for more human behavior than any other motive.

Our social drive is not something we learn. As social neuroscientist Matthew Lieberman describes it, “Our social operating system is part of the basic components of who we are as mammals.” It’s in our nature to have as the center of one’s life not as “me,” but as “us.”

“We give ourselves too much credit when things go well and too much blame when things don’t work out.”

We have, though, put the self at the center of Western life in the twenty-first century. In the process, we have untethered ourselves from the whole of who we are. Never has the idea of a separate self occupied such a prominent place in society. The self has supplanted the group as the basic building block of society. Individual rights, needs, and wants are sacrosanct, and the individual is the filter through which we view economic, legal, and moral problems. Uncoupling the self from a larger social context creates a host of conditions that fuel our fear of people’s opinions.

In the culture of self, both achievements and failures are perceived to depend entirely on one’s own efforts. While that idea can be a source of motivation (you can change the world), it can also undermine our self-esteem. When we identify as a separate self, we take authorship of what happens around us, including things we don’t control. Life unfolds. Things happen. And then we layer on the subjective interpretation that they are happening to me. They are happening because of me, because of something I am doing or not doing. We give ourselves too much credit when things go well and too much blame when things don’t work out.

We turn our experiences against ourselves and they become a referendum on our self. We feel like we are not enough—impostors. Consequently, we are continually in pursuit of our worth and evading the fear of our inadequacy. We are running to stay ahead of our self-judgments and the opinions and judgments of others.

The ever-present need to prove our self distances us from others and undermines our relationships. The focus is on meeting the needs of oneself, not the other person or the relationship. In the process, we often put ourselves in competition, rather than collaboration, with the other person. Rather than being a part of the circle of people we trust, we push them away, often into the realm of fearing people’s opinions.

3. The spotlight effect fuels FOPO.

Cornell Professor Thomas Gilovich and his team carried out a social experiment that revealed a central factor behind our susceptibility to FOPO: we grossly overestimate the attention that others pay to us. We think all eyes are observing our every move. This phenomenon exacerbates our fear of people’s opinions, as we often believe that every small mistake or imperfection is being closely scrutinized and judged. But it’s not true.

Underlying the phenomenon is an egocentric bias. We live at the center of our own worlds. We are acutely focused on our own behavior and appearance, and we tend to believe that other people are equally focused on us. That doesn’t imply we are self-absorbed. Rather, our worldview is a product of our own experiences and perspective, and we attempt to understand other people’s thoughts and actions through that same lens.

The truth is, others are not focused on us like we are focused on ourselves. To varying degrees, everyone walks around with their own spotlight. They, too, are at the center of their own universes. They are wondering if their hair is out of place. They are wondering if you judged them for walking in late to the meeting. They are wondering if you admired the brilliant insight they offered on your team call.

As David Foster Wallace reminded us in his book Infinite Jest, “You will become way less concerned with what other people think of you when you realize how seldom they do.”

4. We preemptively try to gain approval or avoid rejection.

The value we place on social approval is rooted in our evolutionary history. As social creatures, our survival depended on our ability to function within a group. Being accepted by the group was crucial, so we developed a heightened sensitivity to the opinions of others. However, in the modern world, this concern has become an unproductive obsession.

FOPO is an anticipatory mechanism that involves psychological, physiological, and physical activation to avoid rejection and get approval. FOPO is an exhaustive attempt to preempt a negative opinion by persistently interpreting clues in our environment. We read body language, micro-expressions, words, silence, actions, and inactions.

We want to prevent an unfavorable opinion that has not yet occurred, and may not happen at all, but presents a potential threat. Unsure about the other person’s intent, we rely on our own interpretation of what they are thinking about us.

“FOPO depletes our internal resources and undermines quality of life.”

Instead of Oh, I’d better course-correct based on real feedback about an event and my own internal perspective, FOPO attempts to look around corners: Oh, I’d better course-correct before I receive any confirming data based on what I imagine could happen.

FOPO is characterized by a hypervigilant social readiness. Like an application that quietly runs in the background of a computer and consumes memory, processing power, battery life, and slows down performance, FOPO depletes our internal resources and undermines quality of life.

5. Basing one’s self-worth on performance results.

We live in a performance-obsessed culture. A fixation with performance has seeped into business, school, youth sports, social media, and it’s reflected in popular culture. Podcasts offer signposts to finding mastery. Books unlock greatness codes, strip-mine wisdom from outliers, and reveal the tools of titans. Consulting giants promise to “equip people and organizations to unleash sustained performance.” Celebrity instructors share their journeys in online courses. Top ten lists show (nonexistent) shortcuts and hacks to the high-performance mountaintop.

Technology has leapt into the performance party. Driven by the adage, “You can’t improve what you can’t measure,” we now have performance metrics for almost everything we do. Digital devices and apps measure the substrata of human performance. Hours slept. Calories consumed. Time managed. Workflow. Productivity. Engagement. Well-being. Impressions. Followers. Likes. Comments. Social reach. Clickthrough rates. Breaths taken. Breaths held.

Out of that obsession, a new form of identity has emerged: the performance-based identity. When our identity is linked to performance, the quality of our performance defines who we are. We arrive at an understanding of who we are by comparing our performance results to others.

We think that if we successfully perform, then we’ll feel good about ourselves. If I get that book published…If I can close that deal…If I get that promotion…If I get through that to do list…If I make the honor roll…If I’m the top sales agent again this year…If I get nominated for an Academy Award…If I win our local club tournament… …If my social post goes viral….Our self-esteem becomes contingent on our performance. Achieving our performance objective only provides temporary relief because just behind that performance lies the next one. Our self-esteem becomes the byproduct of a series of “if then” statements and we end up on a never-ending loop in pursuit of self-worth.

The pursuit of excellence and high-performance is important. We learn about ourselves by doing difficult things and testing the boundaries of our perceived limits. But when the core motivation of pursuing excellence is proving our self-worth, mistakes, failures, opinions, and criticism are experienced as threats rather than learning opportunities.

Developmental scientist and USC associate research professor Dr. Ben Houltberg, who has extensively studied the motivations behind the pursuit of excellence, points out that identity does not operate just inside a person’s domain of expertise. “It’s a pattern of thinking that gets transferred to other areas.” It shows up in relationships. It plays out at work and in parenting. “If it’s not dealt with, it cascades throughout your life to the point that you always feel like your worth and identity are based on your performance.”

To listen to the audio version read by author Michael Gervais, download the Next Big Idea App today: